How to Build gRPC Services

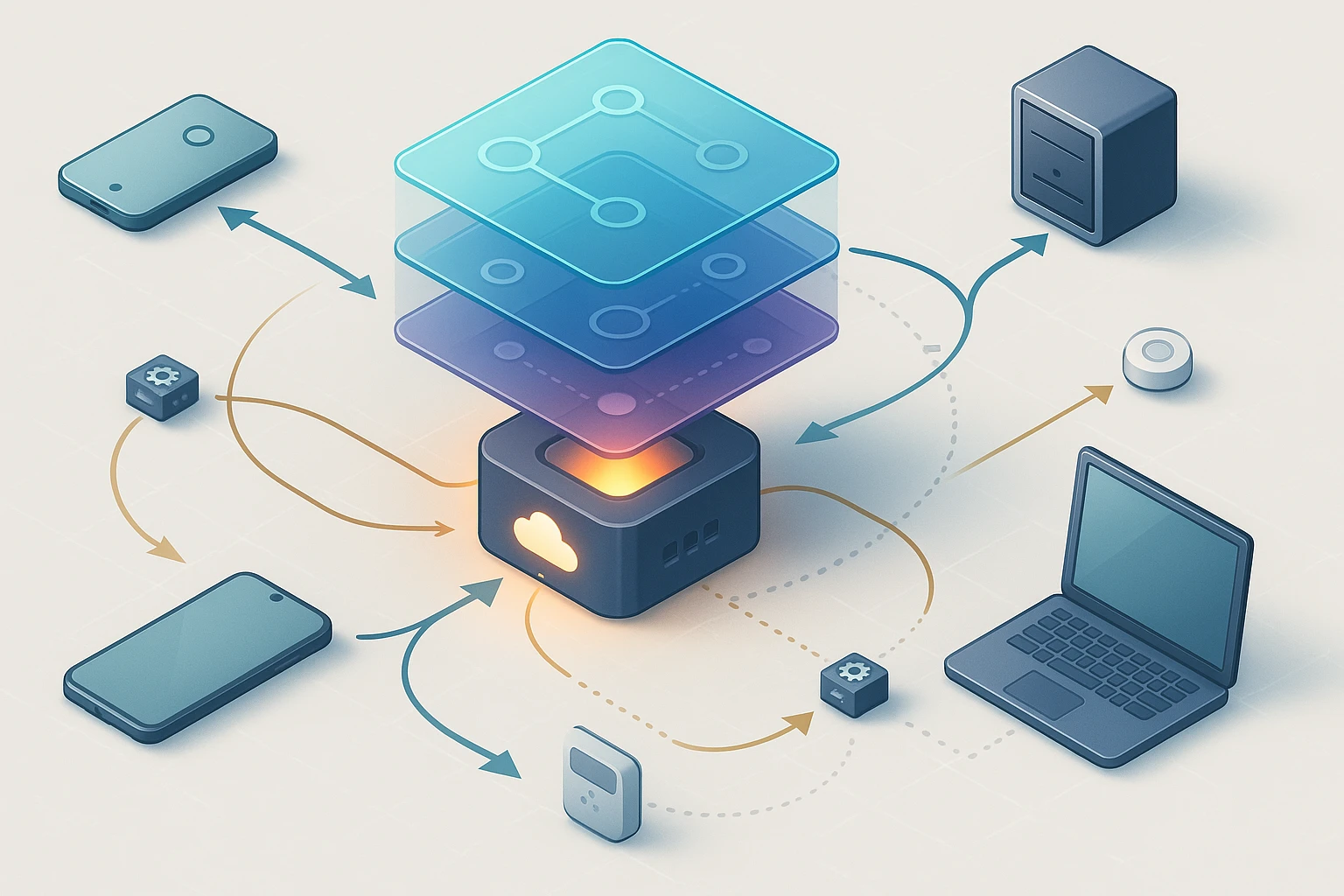

Illustration of building gRPC services: developer coding protobufs, defining RPC methods, client-server diagram showing secure channels, unary and streaming calls, deploymentCI/CD.

Understanding the Critical Role of gRPC in Modern Software Architecture

In today's interconnected digital landscape, the ability to establish efficient, reliable communication between distributed systems has become absolutely essential. Whether you're building microservices that need to exchange data at lightning speed, creating mobile applications that demand minimal battery consumption, or architecting cloud-native platforms that scale across continents, the communication protocol you choose fundamentally shapes your system's performance, maintainability, and future growth potential. Traditional REST APIs, while familiar and widely adopted, often struggle with performance bottlenecks, versioning challenges, and the overhead of text-based serialization when systems reach enterprise scale.

gRPC represents a high-performance, open-source framework originally developed by Google that leverages HTTP/2 protocol features and Protocol Buffers for efficient binary serialization. Unlike conventional approaches, it provides strongly-typed service contracts, automatic code generation across multiple programming languages, built-in authentication mechanisms, and bidirectional streaming capabilities. This combination delivers not just incremental improvements but transformative advantages in latency reduction, bandwidth efficiency, and developer productivity. The framework supports four distinct communication patterns: unary calls resembling traditional request-response, server streaming for real-time data feeds, client streaming for uploading large datasets, and bidirectional streaming enabling full-duplex communication channels.

Throughout this comprehensive exploration, you'll gain practical knowledge on defining service contracts using Protocol Buffers, implementing server-side logic across popular programming languages, establishing secure client connections, handling complex streaming scenarios, implementing robust error management strategies, and deploying production-ready services with monitoring capabilities. Whether you're transitioning from REST architectures or building greenfield projects, you'll discover actionable patterns, common pitfalls to avoid, and architectural decisions that separate proof-of-concept implementations from enterprise-grade systems that handle millions of requests daily.

Establishing Your Development Environment

Before writing any service code, you need a properly configured development environment with the appropriate tools, compilers, and dependencies. The specific requirements vary depending on your chosen programming language, but certain foundational elements remain consistent across all implementations.

Start by installing the Protocol Buffer compiler (protoc), which transforms your service definitions into language-specific code. This compiler is available as pre-built binaries for major operating systems or can be compiled from source. For most developers, downloading the latest release from the official GitHub repository provides the quickest path forward. Verify your installation by running the version command in your terminal—you should see output confirming version 3.x or higher for optimal compatibility with modern features.

Next, install the language-specific gRPC runtime library and code generation plugins. For Python developers, this means pip-installing grpcio and grpcio-tools packages. Go developers need to fetch the google.golang.org/grpc module and install the protoc-gen-go-grpc plugin. Java developers typically add Maven or Gradle dependencies for grpc-netty, grpc-protobuf, and grpc-stub artifacts. Node.js developers install @grpc/grpc-js and @grpc/proto-loader packages. Each language ecosystem has its own package manager and conventions, but the underlying concepts remain remarkably similar.

"The initial tooling setup often feels overwhelming, but investing time in automation and understanding your build pipeline pays dividends throughout the entire development lifecycle."

Organizing Your Project Structure

Establishing a logical project structure from the beginning prevents organizational debt that becomes increasingly difficult to refactor as your service portfolio grows. A recommended approach separates protocol definitions from implementation code, allowing multiple services to share common message types while maintaining clear boundaries between different functional domains.

Create a dedicated directory for your .proto files, typically named "proto" or "api" at your project root. Within this directory, organize definitions by domain or service grouping rather than technical layers. For example, a user management domain might contain user_service.proto, authentication.proto, and common message definitions in shared.proto. This domain-driven organization aligns with microservice boundaries and makes it easier for teams to understand ownership and dependencies.

Your implementation code should reside in separate directories, often structured by programming language conventions. A multi-language repository might have "server" and "client" directories, each containing language-specific subdirectories. Generated code from protoc should ideally be placed in a "generated" or "gen" directory, clearly distinguishing it from handwritten code. Many teams add these generated directories to .gitignore and regenerate them during build processes, ensuring consistency and preventing merge conflicts in auto-generated files.

Defining Service Contracts with Protocol Buffers

Protocol Buffers serve as the interface definition language for gRPC services, providing a language-neutral way to specify data structures and service methods. These definitions become the contract between clients and servers, enabling type-safe communication and automatic code generation.

Begin your .proto file with syntax declaration and package definition. The syntax declaration should specify "proto3", the current recommended version that simplifies many aspects compared to proto2. The package declaration creates a namespace preventing naming conflicts when multiple proto files are compiled together. Following these, add import statements for any shared definitions, such as timestamp types from google/protobuf/timestamp.proto or empty messages from google/protobuf/empty.proto.

Message definitions describe the data structures exchanged between clients and servers. Each message contains fields with specific types, unique field numbers, and optional modifiers. Field numbers are critical—they identify fields in the binary encoding and must never be changed once a message is deployed, as doing so breaks backward compatibility. Choose field numbers below 16 for frequently used fields to optimize encoding size, as these require only one byte to encode.

| Field Type | Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Scalar Types (int32, string, bool) | Basic data types for simple values | User IDs, names, status flags |

| Repeated Fields | Variable-length arrays of values | Lists of items, tags, permissions |

| Nested Messages | Complex structures containing other messages | Address within user profile, metadata objects |

| Enums | Predefined set of named constants | Status codes, user roles, operation types |

| Maps | Key-value pairs with typed keys and values | Configuration settings, attribute dictionaries |

| Oneof | Exactly one field from a set is populated | Union types, polymorphic responses |

Designing Service Methods

Service definitions declare the RPC methods your server implements and clients invoke. Each method specifies a request message type and response message type, along with streaming modifiers if applicable. Method names should follow clear naming conventions—typically verbs for actions (CreateUser, GetOrder) or verb-noun combinations for clarity (ListProducts, UpdateInventory).

Unary methods represent the simplest pattern, where a client sends one request and receives one response. These work identically to traditional function calls but operate across network boundaries. Server streaming methods allow the server to send multiple response messages in reply to a single client request, ideal for scenarios like real-time updates or paginated results where the full dataset is too large for a single response.

Client streaming methods enable clients to send a sequence of messages to the server, which processes them and returns a single response. This pattern works well for uploading files, batch processing operations, or aggregating data from the client side. Bidirectional streaming provides the most flexible pattern, allowing both client and server to send message streams independently, enabling full-duplex communication for chat applications, collaborative editing, or real-time gaming.

"Choosing the right method type isn't just about technical capabilities—it fundamentally shapes how clients interact with your service and influences everything from error handling to testing strategies."

Implementing Server-Side Logic

With your service contract defined, implementing the server involves creating concrete implementations of the generated service interfaces. The generated code provides base classes or interfaces that you extend or implement, filling in the actual business logic for each RPC method.

Server implementations follow a consistent pattern across languages. You create a class that inherits from or implements the generated service base, override each RPC method, and implement your business logic within those methods. Each method receives a request object (containing the client's data) and a context object (providing metadata, deadlines, and cancellation signals), then returns a response object or raises an error.

Inside each method implementation, you'll typically validate input parameters, perform authorization checks, execute business logic (which might involve database queries, external API calls, or complex calculations), construct a response message, and return it to the client. Error conditions should be communicated through gRPC status codes rather than exceptions in most cases, providing clients with structured error information.

Handling Streaming Requests

Streaming methods require different implementation patterns than unary calls. For server streaming, your method typically performs some initial setup, then enters a loop where it sends multiple response messages. You'll use a response stream object provided by the framework, calling a send or write method for each message. The method completes when you exit the function, signaling to the client that no more messages will be sent.

Client streaming methods receive a request stream object that you iterate over to receive messages from the client. Your implementation processes each message as it arrives, potentially accumulating state, then returns a single response after the client finishes sending. The framework handles the complexity of receiving messages asynchronously while your code focuses on processing logic.

Bidirectional streaming combines both patterns—you receive a request stream and have access to a response stream, allowing you to send and receive messages independently. Common patterns include echoing responses for each request, accumulating requests and sending periodic summaries, or implementing completely independent send and receive loops that communicate through shared state.

Managing Server Lifecycle

A production-ready server needs proper initialization, graceful shutdown, and resource management. Server initialization involves creating a server instance, registering your service implementations, optionally configuring interceptors for cross-cutting concerns, binding to network ports, and starting the server's event loop.

Graceful shutdown ensures in-flight requests complete before the server terminates. Most gRPC implementations provide a shutdown method that stops accepting new connections while allowing existing RPCs to finish within a timeout period. Implementing signal handlers for SIGTERM and SIGINT enables your server to shut down cleanly when deployed in containerized environments or managed by process supervisors.

| Server Configuration | Purpose | Typical Values |

|---|---|---|

| Max Concurrent Streams | Limits simultaneous RPCs per connection | 100-1000 depending on resource constraints |

| Max Message Size | Prevents memory exhaustion from large messages | 4MB default, increase for file transfers |

| Keepalive Time | Detects broken connections proactively | 2 hours default, reduce for mobile clients |

| Connection Timeout | Limits time to establish connections | 20 seconds typical for internet-facing services |

| Thread Pool Size | Controls concurrent request processing capacity | CPU count × 2 for CPU-bound, higher for I/O-bound |

Building Client Applications

Client implementation begins with generating client stub code from your proto definitions, then creating instances of the generated client class. These stubs provide methods corresponding to each RPC defined in your service, handling serialization, network communication, and deserialization automatically.

Creating a client involves establishing a channel (the connection to the server), instantiating a stub with that channel, and invoking methods on the stub as if they were local function calls. Channels represent the underlying HTTP/2 connection and handle connection pooling, load balancing, and retry logic. Most implementations allow you to configure channels with various options controlling timeouts, compression, and authentication.

When invoking unary methods, the call blocks until the server responds or an error occurs. You receive the response message directly and can handle any errors through exception catching or error return values, depending on your language. This synchronous pattern works well for simple request-response scenarios but can limit concurrency in high-throughput clients.

Implementing Asynchronous Clients

For applications requiring high concurrency or non-blocking behavior, asynchronous client patterns become essential. Most gRPC implementations provide async variants of stub methods that return futures, promises, or integrate with language-specific async/await patterns. These allow your application to initiate multiple RPCs concurrently without blocking threads.

Streaming calls require different client-side patterns. Server streaming methods return an iterator or stream object that you consume to receive messages. Your code typically loops over this iterator, processing each message as it arrives until the server closes the stream. Client streaming methods provide a stream object you write messages to, then close when finished and await the server's response.

Bidirectional streaming provides both a request stream and response stream, allowing your client to send and receive independently. Common patterns include spawning separate threads or async tasks for sending and receiving, or implementing a message pump that alternates between sending and receiving based on application logic.

"Client implementation complexity often sneaks up on developers—what starts as simple request-response calls evolves into sophisticated error handling, retry logic, and connection management that rivals server-side complexity."

Implementing Security and Authentication

Production services require robust security mechanisms protecting data in transit and ensuring only authorized clients can invoke operations. gRPC provides multiple security layers, from transport security to application-level authentication and authorization.

Transport Layer Security (TLS) encrypts all data transmitted between clients and servers, preventing eavesdropping and man-in-the-middle attacks. Implementing TLS requires obtaining certificates—either from a public Certificate Authority for internet-facing services or generating self-signed certificates for internal services. Server configuration involves loading the certificate and private key, while clients configure the channel to verify server certificates against trusted root CAs.

For development and testing, self-signed certificates work adequately, but production deployments should use certificates from trusted CAs or internal PKI infrastructure. Many cloud platforms provide certificate management services that automatically handle renewal, simplifying operational overhead. Certificate rotation requires careful planning to avoid service disruptions—implementing graceful certificate reloading allows servers to pick up new certificates without downtime.

Token-Based Authentication

Application-level authentication typically uses token-based schemes where clients present credentials to obtain tokens, then include those tokens in subsequent RPC calls. The most common pattern uses OAuth 2.0 access tokens or JSON Web Tokens (JWT) passed in metadata headers.

Implementing token authentication on the server side involves creating an interceptor that extracts tokens from request metadata, validates them (checking signatures, expiration, and claims), and makes authorization decisions based on token contents. Interceptors provide a clean separation between authentication logic and business logic, allowing you to apply authentication consistently across all methods or selectively to specific operations.

Client-side token management requires obtaining tokens through an authentication flow, storing them securely, attaching them to RPC calls through metadata, and handling token refresh when tokens expire. Many implementations provide credential helpers that automate token attachment, but you're responsible for the initial authentication and refresh logic.

Error Handling and Status Codes

Robust error handling distinguishes production-ready services from prototypes. gRPC defines a standard set of status codes that communicate different error conditions to clients, enabling appropriate handling strategies for each situation.

Status codes range from OK (successful completion) through various error conditions like INVALID_ARGUMENT (client error), PERMISSION_DENIED (authorization failure), INTERNAL (server error), and UNAVAILABLE (temporary failure). Choosing the correct status code helps clients implement appropriate retry logic—some errors like INVALID_ARGUMENT should never be retried, while UNAVAILABLE errors often warrant retry with backoff.

Beyond status codes, gRPC supports detailed error information through status details—additional proto messages attached to errors providing structured information about what went wrong. This mechanism allows services to return validation errors with field-level details, quota information explaining rate limit violations, or debugging information for internal errors.

Implementing Retry Logic

Network communication inherently involves transient failures—servers restart, networks experience packet loss, load balancers route requests to unhealthy instances. Implementing intelligent retry logic in clients improves reliability without requiring server changes.

Effective retry strategies consider multiple factors: which status codes warrant retry, how many attempts to make, how long to wait between attempts, and how to avoid overwhelming struggling servers. Exponential backoff with jitter represents the gold standard—doubling wait time between attempts while adding random variation prevents thundering herd problems where many clients retry simultaneously.

Some gRPC implementations support automatic retry configuration through service configuration, allowing you to specify retry policies declaratively rather than implementing retry loops manually. These configurations can specify which status codes trigger retries, maximum attempts, and backoff parameters, providing consistent behavior across your client applications.

"The difference between a system that handles errors gracefully and one that cascades failures often comes down to thoughtful retry policies and circuit breakers that prevent retry storms."

Implementing Interceptors and Middleware

Interceptors provide a powerful mechanism for implementing cross-cutting concerns that apply to multiple or all RPC methods without duplicating code. They work similarly to middleware in web frameworks, wrapping RPC invocations and allowing you to execute code before and after the actual method implementation.

Common use cases for server-side interceptors include authentication and authorization, logging and metrics collection, request validation, rate limiting, and error transformation. By implementing these concerns as interceptors, you keep your service methods focused on business logic while applying consistent policies across your entire service.

Creating an interceptor typically involves implementing a specific interface or extending a base class provided by your gRPC library. The interceptor receives the incoming request, context, and a continuation function that invokes the next interceptor or the actual method implementation. You can inspect and modify the request, invoke the continuation, then inspect and modify the response before returning it to the client.

Client-Side Interceptors

Client interceptors enable similar cross-cutting concerns on the client side. Common applications include attaching authentication tokens to requests, implementing client-side metrics and logging, adding request tracing headers, and implementing custom retry logic that goes beyond the framework's built-in capabilities.

The implementation pattern mirrors server-side interceptors—you receive the request, metadata, and a continuation function, allowing you to modify outgoing requests and inspect incoming responses. Multiple interceptors can be chained together, executing in order for outgoing requests and reverse order for incoming responses, providing flexible composition of behaviors.

Monitoring and Observability

Operating services in production requires visibility into their behavior, performance, and health. Comprehensive monitoring encompasses metrics collection, distributed tracing, structured logging, and health checking mechanisms.

Metrics provide quantitative measurements of service behavior over time. Essential metrics include request rate (requests per second), error rate (percentage of failed requests), and latency distribution (p50, p95, p99 percentiles). Additional metrics might track payload sizes, active connections, thread pool utilization, and business-specific measurements. Most teams integrate with metrics systems like Prometheus, exporting metrics in standard formats that monitoring infrastructure can scrape and visualize.

Distributed tracing helps understand request flows across multiple services. When a client request triggers calls to multiple backend services, tracing connects these operations into a single trace, showing the complete request path, timing of each operation, and where errors occurred. Implementing tracing typically involves integrating with systems like Jaeger or Zipkin, using interceptors to propagate trace context between services.

Health Checking

Health checks allow orchestration systems, load balancers, and monitoring tools to determine whether a service instance is healthy and ready to receive traffic. gRPC defines a standard health checking protocol that services can implement, providing a consistent interface for health queries.

The health checking service defines a simple RPC that returns the serving status for the overall server or specific services. Implementations typically check dependencies like database connections, external API availability, and resource utilization before reporting healthy status. Sophisticated health checks distinguish between "serving" (ready to handle requests) and "not serving" (temporarily unavailable but will recover) versus "unknown" (health cannot be determined).

"Observability isn't about collecting every possible metric—it's about instrumenting your systems so you can ask and answer questions about their behavior when problems occur."

Load Balancing and Service Discovery

Deploying services across multiple instances for scalability and reliability requires mechanisms to distribute requests across those instances and discover available instances dynamically. gRPC supports multiple load balancing approaches, each with different trade-offs.

Client-side load balancing gives clients responsibility for distributing requests across service instances. Clients maintain connections to multiple server instances and implement load balancing algorithms (round-robin, least-request, weighted) to choose which instance receives each request. This approach eliminates the single point of failure and latency overhead of proxy-based load balancers but requires clients to implement more complex logic.

Service discovery integration allows clients to dynamically discover available service instances rather than hard-coding addresses. Popular approaches include DNS-based discovery (where DNS returns multiple IP addresses), integration with service meshes like Istio or Linkerd, or using dedicated service discovery systems like Consul or etcd. The gRPC resolver and load balancer interfaces provide extensibility points for integrating with different discovery mechanisms.

Implementing Custom Load Balancers

While built-in load balancing algorithms work well for many scenarios, some applications require custom logic. You might implement weighted load balancing based on instance capacity, locality-aware routing that prefers nearby instances, or application-specific routing based on request attributes.

Creating custom load balancers involves implementing the load balancer interface provided by your gRPC library. The interface typically requires implementing a picker that chooses which subchannel (connection to a specific instance) should handle each request. Your picker can access request metadata, maintain state about instance health and performance, and implement arbitrary selection logic.

Testing Strategies

Comprehensive testing ensures your services behave correctly under various conditions. Effective testing strategies span multiple levels, from unit tests of individual methods to integration tests of complete service interactions to load tests verifying performance under stress.

Unit testing service implementations requires creating test doubles for dependencies and invoking service methods directly. Most gRPC frameworks provide testing utilities that simplify creating request contexts, capturing responses, and asserting on status codes and response contents. Testing streaming methods requires additional infrastructure to feed test messages and collect responses over time.

Integration testing involves running actual server and client instances, exercising complete request flows including serialization, network communication, and deserialization. These tests verify that generated code, service implementations, and client code work together correctly. Test containers or embedded servers simplify integration testing by allowing tests to start isolated server instances without external dependencies.

Load and Performance Testing

Performance testing verifies that services meet latency and throughput requirements under realistic load. Tools like ghz provide gRPC-specific load testing capabilities, allowing you to generate configurable request rates, measure latency distributions, and identify performance bottlenecks.

Effective load tests gradually increase request rates while monitoring key metrics, identifying the point where latency degrades or error rates increase. Testing should include scenarios with varying payload sizes, different method types (unary vs. streaming), and realistic distributions of operations. Performance testing in production-like environments provides the most accurate results, accounting for network characteristics and infrastructure limitations.

Deployment Considerations

Deploying gRPC services in production environments requires addressing several operational concerns beyond basic functionality. Container orchestration platforms like Kubernetes have become the standard deployment target, but gRPC's use of HTTP/2 creates some specific considerations.

HTTP/2 connection multiplexing means a single TCP connection carries multiple simultaneous requests, improving efficiency but complicating load balancing. Many L4 load balancers operate at the connection level, routing based on TCP connections rather than individual requests. With long-lived HTTP/2 connections, this can result in uneven load distribution. Solutions include using L7 load balancers that understand HTTP/2, implementing client-side load balancing, or deploying service mesh infrastructure.

Container health checks need special consideration because gRPC doesn't use traditional HTTP endpoints. Kubernetes supports gRPC health checks natively in recent versions, but older versions require workarounds like implementing an HTTP health endpoint alongside your gRPC service or using command-based health checks that invoke grpc-health-probe.

Configuration Management

Managing service configuration across different environments (development, staging, production) requires structured approaches that prevent errors and enable easy updates. Configuration typically includes addresses of dependent services, database connection strings, feature flags, and operational parameters like timeouts and pool sizes.

Modern approaches favor externalized configuration through environment variables, configuration files mounted into containers, or dedicated configuration services like Consul or etcd. Avoid embedding configuration in compiled code—it prevents using the same binary across environments and requires recompilation for configuration changes. Sensitive configuration like credentials and API keys should be managed through secrets management systems rather than plain configuration files.

Advanced Patterns and Techniques

Beyond basic request-response patterns, several advanced techniques enable sophisticated behaviors in distributed systems. Understanding these patterns helps you design more resilient, efficient, and maintainable services.

💡 Hedged Requests improve tail latency by sending duplicate requests to multiple service instances after a delay, using whichever responds first. This technique trades increased resource usage for more consistent latency, particularly valuable for user-facing services where p99 latency matters.

⚡ Request Coalescing combines multiple identical requests into a single backend request, reducing load on downstream services. When multiple clients request the same data simultaneously, coalescing executes one backend request and distributes the response to all waiting clients.

🔄 Circuit Breaking prevents cascading failures by detecting when a downstream service becomes unhealthy and temporarily stopping requests to it. After a timeout, the circuit breaker allows test requests through to check if the service has recovered, reopening the circuit if successful.

🎯 Bulkheading isolates resources for different operations, preventing one operation from consuming all available resources and starving others. You might maintain separate thread pools or connection pools for different RPC methods, ensuring critical operations always have resources available.

🛡️ Rate Limiting protects services from overload by restricting the number of requests accepted within time windows. Implementation options range from simple token bucket algorithms to sophisticated distributed rate limiting using shared state in Redis or similar systems.

Implementing Backward Compatibility

Services evolve over time, adding new features and modifying existing behaviors. Maintaining backward compatibility ensures that existing clients continue working when services are updated, avoiding coordination requirements between client and server deployments.

Protocol Buffers provide strong backward compatibility guarantees when you follow specific rules: never change field numbers, never change field types, only add new fields (never remove), and use default values appropriately. Adding new RPC methods is always safe—old clients simply won't invoke them. Adding fields to existing messages is safe if clients ignore unknown fields, which is the default behavior.

More complex changes require versioning strategies. Options include running multiple service versions simultaneously, implementing version-aware routing that directs clients to appropriate server versions, or using feature flags to enable new behaviors conditionally. The right approach depends on your deployment model, client update patterns, and organizational constraints.

"Backward compatibility isn't just a technical constraint—it's a contract with your users that their investments in your platform remain valuable as you evolve."

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even experienced developers encounter challenges when building gRPC services. Understanding common mistakes helps you avoid them in your implementations.

One frequent issue involves blocking operations in asynchronous contexts. When using async/await patterns, calling synchronous blocking operations can deadlock or severely degrade performance. Always use async variants of I/O operations, and be particularly careful with database clients and HTTP clients that may offer both sync and async APIs.

Another common mistake is ignoring deadline propagation. When service A calls service B, which calls service C, deadlines should propagate through the chain. If A gives B a 5-second deadline, B should give C a deadline shorter than 5 seconds to account for processing time. Failing to propagate deadlines can result in wasted work processing requests that have already timed out from the client's perspective.

Resource leaks represent another category of problems. Streaming calls that aren't properly closed can leak memory and file descriptors. Always implement proper cleanup in finally blocks or using language-specific resource management constructs. Server implementations should handle client disconnections gracefully, stopping processing and releasing resources when clients disappear.

Many developers underestimate the importance of message size limits. While gRPC handles large messages, unbounded message sizes can exhaust memory. Set reasonable maximum message sizes based on your use cases, and design APIs that handle large data transfers through streaming rather than single large messages.

Performance Optimization Techniques

While gRPC provides excellent baseline performance, understanding optimization techniques helps you achieve maximum efficiency for demanding applications.

Message design significantly impacts performance. Smaller messages serialize faster and consume less bandwidth. Use appropriate field types—int32 instead of int64 when values fit, bytes instead of string for binary data. Consider using oneof for messages where only one field is populated, reducing serialization overhead. Avoid deeply nested messages when possible, as they increase serialization complexity.

Connection pooling and reuse dramatically improve performance by amortizing connection establishment costs. Create channels once and reuse them across requests rather than creating new channels for each operation. Most gRPC implementations handle connection pooling automatically, but you need to structure your code to share channel instances.

Compression can reduce bandwidth usage at the cost of CPU overhead. gRPC supports multiple compression algorithms, with gzip being the most common. Enable compression for large messages or slow networks, but measure the impact—compression adds latency and CPU usage that may not be worthwhile for small messages or fast networks.

Profiling and Benchmarking

Optimization requires measurement. Profile your services to identify actual bottlenecks rather than optimizing based on assumptions. Most languages provide profiling tools that show CPU usage, memory allocation, and time spent in different functions.

Create benchmarks that measure specific operations under realistic conditions. Benchmark different message sizes, various payload types, and different concurrency levels. Track benchmark results over time to detect performance regressions. Automated benchmarking in CI/CD pipelines helps catch performance problems before they reach production.

What are the main advantages of gRPC over REST APIs?

gRPC offers several key advantages: significantly lower latency due to binary serialization and HTTP/2 multiplexing, strongly-typed contracts that catch errors at compile time, automatic code generation reducing boilerplate, built-in streaming support for real-time scenarios, and better performance under high load. REST remains simpler for browser-based clients and public APIs, but gRPC excels in microservice communication, mobile backends, and performance-critical systems.

How do I handle versioning and backward compatibility in gRPC services?

Protocol Buffers provide strong backward compatibility when you follow key rules: never reuse field numbers, only add new fields (never remove existing ones), never change field types, and use reserved keywords for removed fields. For larger changes, consider running multiple service versions simultaneously with version-aware routing, or use feature flags to enable new behaviors conditionally while maintaining the same service interface.

What's the recommended approach for error handling in gRPC?

Use appropriate gRPC status codes to communicate error types—INVALID_ARGUMENT for client errors, INTERNAL for server errors, UNAVAILABLE for temporary failures. Attach detailed error information using status details for structured error data. Implement retry logic on clients for transient errors with exponential backoff. Use interceptors to implement consistent error handling and logging across all methods without duplicating code.

How should I secure gRPC services in production?

Implement multiple security layers: use TLS for transport encryption with certificates from trusted CAs, implement token-based authentication (OAuth 2.0 or JWT) for identity verification, use interceptors for authorization checks, validate all input data, implement rate limiting to prevent abuse, and use mutual TLS for service-to-service communication in zero-trust environments. Consider deploying a service mesh for comprehensive security policy enforcement.

What's the best way to test gRPC services?

Implement multiple testing levels: unit tests for individual service methods using test doubles, integration tests with real server and client instances to verify end-to-end functionality, contract tests to ensure client-server compatibility, load tests to verify performance under stress, and chaos engineering experiments to validate resilience. Use testing utilities provided by gRPC libraries and consider tools like ghz for load testing and Testcontainers for integration testing.

How do I implement effective monitoring for gRPC services?

Collect key metrics including request rate, error rate, and latency distributions (p50, p95, p99), implement distributed tracing to track requests across services, use structured logging for debugging, implement the standard gRPC health checking protocol, create dashboards visualizing service health and performance, and set up alerts for anomalous conditions. Use interceptors to implement monitoring consistently across all methods.