How to Design RESTful API Best Practices

RESTful API best practices: resource-focused URIs, stateless servers, correct HTTP verbs and status codes, HATEOAS, versioning, pagination, security, error handling, clear docs.org

How to Design RESTful API Best Practices

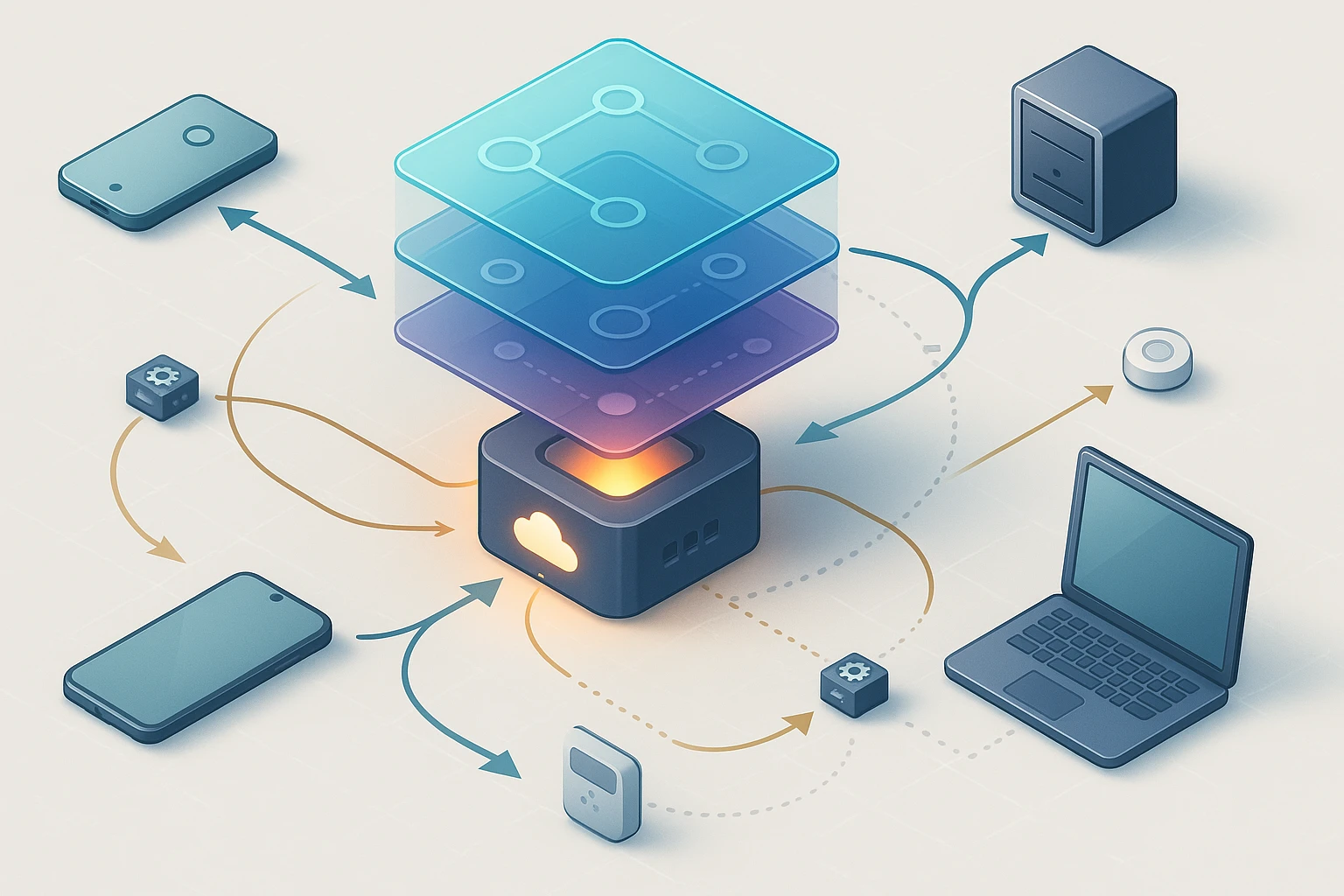

In today's interconnected digital ecosystem, the way systems communicate with each other determines the success or failure of entire platforms. Whether you're building a mobile application, integrating third-party services, or creating a microservices architecture, the design of your API becomes the foundation upon which everything else stands. Poor API design leads to frustrated developers, security vulnerabilities, performance bottlenecks, and ultimately, failed products that never reach their potential.

RESTful API design represents an architectural style that leverages HTTP protocols to create scalable, maintainable, and intuitive interfaces between software systems. It's not merely about making endpoints work—it's about crafting an experience that developers understand instinctively, that scales effortlessly as your user base grows, and that remains flexible enough to evolve with changing business requirements. This approach combines technical precision with thoughtful consideration of how humans interact with technology.

Throughout this comprehensive exploration, you'll discover the fundamental principles that separate exceptional API design from mediocre implementations. We'll examine resource naming conventions that make your API self-documenting, HTTP methods that communicate intent clearly, status codes that provide meaningful feedback, versioning strategies that protect existing integrations, security practices that safeguard sensitive data, and performance optimization techniques that keep your services responsive under load. Each section provides actionable insights you can implement immediately, regardless of your technology stack or experience level.

Understanding Resource-Oriented Architecture

The cornerstone of effective RESTful API design lies in thinking about your system in terms of resources rather than actions. Resources represent the nouns of your application domain—users, products, orders, comments—each with its own unique identifier and set of operations. This mental shift from action-oriented RPC-style thinking to resource-oriented design fundamentally changes how you structure your endpoints and how consumers interact with your API.

When identifying resources within your application, focus on the entities that hold business value and have a distinct lifecycle. A user account is a resource because it can be created, retrieved, updated, and eventually deleted. A shopping cart is a resource because it exists independently and maintains state between interactions. Even abstract concepts like search results or analytics reports can be modeled as resources when they represent retrievable information with consistent structure.

Resource hierarchies naturally emerge when you examine relationships between entities. A blog post contains comments, an order contains line items, a user profile contains addresses. These parent-child relationships should be reflected in your URL structure, creating intuitive paths that mirror the logical organization of your data. However, avoid nesting too deeply—more than two or three levels typically indicates an opportunity to rethink your resource modeling.

"The most elegant APIs are those where developers can guess the endpoint structure before reading the documentation, because the resource model aligns perfectly with their mental model of the domain."

Crafting Meaningful Resource Names

Resource naming conventions directly impact how quickly developers can understand and adopt your API. Consistency in naming creates predictability, reducing cognitive load and minimizing the need to constantly reference documentation. Always use plural nouns for collection resources—/users rather than /user, /products instead of /product. This convention clearly signals that the endpoint represents multiple items and maintains consistency across your entire API surface.

Lowercase letters with hyphens for multi-word resources provide the best readability and avoid complications with case-sensitive systems. Choose /order-items over /OrderItems or /order_items. While underscores work technically, hyphens have become the de facto standard in modern API design and align with URL conventions used across the web. This consistency extends beyond your API to how URLs appear in documentation, logs, and error messages.

Avoid verbs in resource names except when modeling operations that don't fit neatly into CRUD patterns. Instead of /getUsers or /createOrder, rely on HTTP methods to convey the action. The endpoint /users with a GET method retrieves users, while the same endpoint with POST creates a new user. This separation of concerns—resources in the URL, actions in the HTTP method—creates cleaner, more maintainable APIs.

| Pattern | Example | Purpose | HTTP Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collection | /api/users | Retrieve all users or create new user | GET, POST |

| Specific Resource | /api/users/12345 | Retrieve, update, or delete specific user | GET, PUT, PATCH, DELETE |

| Nested Collection | /api/users/12345/orders | Retrieve orders belonging to specific user | GET, POST |

| Nested Resource | /api/users/12345/orders/67890 | Retrieve specific order for specific user | GET, PUT, PATCH, DELETE |

| Action Resource | /api/orders/67890/cancel | Perform non-CRUD operation | POST |

Leveraging HTTP Methods Correctly

HTTP provides a rich vocabulary of methods, each with specific semantics that communicate intent and expected behavior. Understanding and respecting these semantics ensures your API behaves predictably and integrates smoothly with the broader HTTP ecosystem, including caching mechanisms, proxies, and client libraries that make assumptions based on standard HTTP behavior.

GET requests retrieve resource representations without causing side effects. They should be idempotent and safe, meaning multiple identical requests produce the same result and don't modify server state. Use GET for fetching individual resources, collections, search results, and any read-only operation. Never use GET for operations that change data, even if it seems convenient—this violates HTTP semantics and breaks caching, bookmarking, and prefetching mechanisms that browsers and proxies rely upon.

POST requests create new resources or trigger operations that don't fit other methods. When creating resources, POST typically targets a collection endpoint like /users, and the server assigns the new resource's identifier. The response should include a Location header pointing to the newly created resource and return a 201 Created status code. POST is neither safe nor idempotent—submitting the same POST request multiple times may create multiple resources or trigger an action multiple times.

PUT requests replace an entire resource with the provided representation. The client specifies the complete resource state, and the server replaces the existing resource entirely. PUT is idempotent—sending the same PUT request multiple times produces the same result as sending it once. If the resource doesn't exist, PUT can create it, though this requires the client to know the resource identifier upfront. Use PUT when clients need full control over resource state and can provide complete representations.

PATCH requests apply partial modifications to resources. Unlike PUT, PATCH only updates the fields included in the request body, leaving other fields unchanged. This proves more efficient for large resources where clients need to modify only a few attributes. PATCH should be idempotent when possible, though the specification doesn't strictly require it. Clearly document which fields can be patched and any validation rules that apply to partial updates.

"Choosing the wrong HTTP method is like using a screwdriver as a hammer—it might work temporarily, but you're fighting against the tool's intended design and will encounter problems as your system grows."

DELETE requests remove resources from the system. Like PUT, DELETE is idempotent—deleting a resource multiple times has the same effect as deleting it once. After successful deletion, subsequent GET requests for that resource should return 404 Not Found. Consider whether you need hard deletes (permanently removing data) or soft deletes (marking resources as inactive while preserving data), and implement appropriate authorization checks since deletion represents an irreversible operation in most cases.

Handling Edge Cases and Special Operations

Some operations don't map cleanly to standard CRUD patterns. Searching, filtering, and complex queries often require special consideration. For simple searches, use GET with query parameters: /products?search=laptop&category=electronics. For complex searches with many parameters or when query strings become unwieldy, consider creating a search resource: POST to /searches with search criteria in the body, returning a search result resource that can be retrieved later.

Bulk operations present another challenge. Rather than forcing clients to make hundreds of individual requests, provide dedicated bulk endpoints. Use POST to /users/bulk with an array of user objects to create multiple users atomically. Return detailed results indicating which operations succeeded and which failed, allowing clients to handle partial failures gracefully. Implement appropriate rate limiting and timeouts for bulk operations to prevent abuse and resource exhaustion.

Actions that don't fit CRUD semantics—canceling an order, publishing a draft, approving a request—can be modeled as sub-resources with POST requests. Instead of PATCH /orders/123 with {"status": "cancelled"}, use POST /orders/123/cancel. This approach makes the operation explicit, allows for operation-specific parameters, and provides a clear audit trail of actions taken on resources. Document these action endpoints thoroughly since they represent domain-specific operations rather than standard REST patterns.

Implementing Proper Status Codes

HTTP status codes provide a standardized way to communicate the outcome of API requests. Using appropriate status codes enables clients to handle responses programmatically, distinguishing between client errors, server errors, and successful operations without parsing response bodies. Consistent status code usage also improves debugging, monitoring, and analytics by providing clear signals about API health and usage patterns.

The 2xx range indicates successful operations. Return 200 OK for successful GET, PUT, or PATCH requests that return response bodies. Use 201 Created for successful POST requests that create resources, including a Location header with the new resource's URL. Return 204 No Content for successful DELETE requests or updates that don't return response bodies, signaling completion without wasting bandwidth on empty responses.

The 4xx range indicates client errors—problems with the request that the client should fix before retrying. Return 400 Bad Request for malformed requests, invalid JSON, or requests that violate validation rules. Include detailed error messages explaining what went wrong and how to fix it. Use 401 Unauthorized when authentication is required but not provided, and 403 Forbidden when authentication succeeded but the user lacks permission for the requested operation.

404 Not Found indicates the requested resource doesn't exist. Return this status for requests to non-existent resource identifiers, not for empty collections—an empty collection is still a valid response that should return 200 OK with an empty array. Use 409 Conflict when a request cannot be completed due to a conflict with current resource state, such as attempting to create a resource that already exists or updating a resource that has been modified since the client last retrieved it.

"Status codes are the API's way of speaking the universal language of HTTP—misuse them, and you force every client to implement custom error handling logic instead of relying on standard HTTP semantics."

The 5xx range indicates server errors—problems on the server side that the client cannot fix by modifying the request. Return 500 Internal Server Error for unexpected server failures, but avoid exposing sensitive implementation details in error messages. Use 503 Service Unavailable when the server is temporarily unable to handle requests due to maintenance or overload, including a Retry-After header indicating when clients should retry. Reserve 502 Bad Gateway and 504 Gateway Timeout for proxy and gateway scenarios.

Crafting Meaningful Error Responses

Status codes alone don't provide enough information for developers to diagnose and fix problems. Supplement status codes with structured error responses that include machine-readable error codes, human-readable messages, and actionable guidance. Design a consistent error response format used across all endpoints, making it easy for client libraries to parse and display errors appropriately.

A well-designed error response includes several key elements. An error code or type that categorizes the error programmatically, allowing clients to handle specific error cases without parsing messages. A human-readable message describing what went wrong in clear, non-technical language. Detailed information about which fields failed validation and why, enabling clients to highlight problematic fields in user interfaces. A documentation link where developers can learn more about the error and how to resolve it.

{

"error": {

"code": "VALIDATION_ERROR",

"message": "The request contains invalid data",

"details": [

{

"field": "email",

"message": "Email address is not valid",

"code": "INVALID_FORMAT"

},

{

"field": "age",

"message": "Age must be between 18 and 120",

"code": "OUT_OF_RANGE"

}

],

"documentation_url": "https://api.example.com/docs/errors/validation"

}

}

Versioning Strategies for Long-Term Maintenance

APIs evolve over time as business requirements change, new features are added, and technical improvements are implemented. Without a clear versioning strategy, these changes break existing integrations, frustrate developers, and damage trust in your platform. Versioning provides a mechanism to introduce changes while maintaining backward compatibility for existing clients, allowing them to migrate on their own timeline.

Several versioning approaches exist, each with tradeoffs. URL versioning includes the version number in the path: /v1/users, /v2/users. This approach makes the version explicit and easy to understand, works with all HTTP clients, and simplifies routing and caching. However, it creates URL proliferation and requires maintaining multiple endpoint implementations simultaneously. URL versioning remains the most popular approach due to its simplicity and visibility.

Header versioning uses a custom header like API-Version: 2 or the Accept header with a custom media type: Accept: application/vnd.example.v2+json. This approach keeps URLs clean and separates versioning concerns from resource identification. However, it makes testing harder since you cannot simply paste URLs into browsers, and some proxies and caching systems struggle with header-based routing. Header versioning works well for APIs consumed primarily by sophisticated clients with proper HTTP libraries.

Query parameter versioning includes version in the query string: /users?version=2. This approach maintains clean URLs while remaining visible and easy to test. However, it complicates caching since query parameters affect cache keys, and it can be confused with filtering parameters. Query parameter versioning works best for APIs where caching isn't critical or where version changes are infrequent.

| Versioning Method | Example | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| URL Path | /v1/users | Explicit, simple, works everywhere | URL proliferation, routing complexity |

| Custom Header | API-Version: 2 | Clean URLs, proper HTTP semantics | Harder to test, caching challenges |

| Accept Header | Accept: application/vnd.api.v2+json | RESTful, content negotiation | Complex implementation, testing difficulty |

| Query Parameter | /users?version=2 | Visible, testable, clean base URLs | Caching complications, parameter confusion |

Managing Breaking Changes

Not all changes require new versions. Additive changes—adding new endpoints, adding optional fields to requests, adding fields to responses—maintain backward compatibility and can be deployed without versioning. Clients ignore unknown response fields and don't use new optional request fields until they're ready. Document these changes clearly so developers can take advantage of new functionality when appropriate.

Breaking changes require new versions because they can break existing clients. These include removing endpoints, removing or renaming fields, changing field types, making optional fields required, changing validation rules to be more restrictive, or modifying response structures in ways that break client parsing logic. When planning breaking changes, batch them together into major version releases rather than releasing new versions for each small change.

"The best versioning strategy is the one that lets you move forward while respecting the investments developers have made in integrating with your API—breaking changes should be rare, well-planned, and accompanied by clear migration paths."

Maintain clear deprecation policies that give developers adequate time to migrate. Announce deprecations well in advance, document migration paths thoroughly, and provide tools or scripts to help automate migration where possible. Continue supporting old versions for a reasonable period—typically 12 to 24 months for public APIs—while encouraging migration through documentation, email notifications, and eventually warning headers in responses from deprecated versions.

Securing Your API Effectively

Security cannot be an afterthought in API design—it must be baked into every decision from the beginning. APIs expose business logic and data to the internet, making them attractive targets for attackers. A comprehensive security strategy addresses authentication, authorization, data protection, rate limiting, and input validation, creating defense in depth that protects your system even when individual security measures fail.

Authentication verifies the identity of clients making requests. Modern APIs typically use token-based authentication rather than session-based authentication. OAuth 2.0 provides a standardized framework for delegated authorization, allowing users to grant limited access to their resources without sharing passwords. For simpler use cases, API keys or JWT tokens provide straightforward authentication mechanisms. Always transmit authentication credentials over HTTPS to prevent interception.

Authorization determines what authenticated clients can access. Implement role-based access control (RBAC) or attribute-based access control (ABAC) to manage permissions granularly. Check authorization at every endpoint—never rely on client-side checks or assume that authentication implies authorization. Return 403 Forbidden when authenticated users lack permission, not 404 Not Found, unless you need to hide the existence of resources from unauthorized users for security reasons.

Implement rate limiting to prevent abuse, protect against denial-of-service attacks, and ensure fair resource allocation among clients. Return 429 Too Many Requests when clients exceed rate limits, including headers that indicate the limit, remaining requests, and when the limit resets: X-RateLimit-Limit: 1000, X-RateLimit-Remaining: 42, X-RateLimit-Reset: 1640000000. Implement different rate limits for different endpoints based on their resource intensity and criticality.

Validate all input rigorously to prevent injection attacks, data corruption, and unexpected behavior. Validate data types, formats, ranges, and business rules. Reject invalid input with clear error messages rather than attempting to coerce or sanitize input—this prevents subtle bugs and security vulnerabilities. Use parameterized queries or ORM frameworks to prevent SQL injection, and sanitize data before including it in responses to prevent cross-site scripting attacks.

Protecting Sensitive Data

Always use HTTPS for API communication, encrypting data in transit and preventing man-in-the-middle attacks. Configure TLS properly with strong cipher suites and up-to-date certificates. Implement HTTP Strict Transport Security (HSTS) headers to prevent protocol downgrade attacks. Never transmit sensitive data like passwords, credit card numbers, or personal information over unencrypted connections, even in development environments.

Avoid including sensitive data in URLs since URLs appear in logs, browser history, and referrer headers. Use request bodies for sensitive data, and implement proper logging practices that redact or mask sensitive information. When returning sensitive data in responses, include only what clients actually need—don't return password hashes, internal identifiers, or other sensitive fields unless absolutely necessary.

"Security is not a feature you add at the end—it's a fundamental property of well-designed systems that must be considered at every layer, from authentication and authorization to data encryption and input validation."

Optimizing Performance and Scalability

Performance directly impacts user experience, operational costs, and your ability to scale. Slow APIs frustrate developers, increase infrastructure costs, and limit the number of clients you can serve. Performance optimization should begin during design rather than being retrofitted later—architectural decisions made early on have profound impacts on performance characteristics that are difficult or impossible to change later.

Pagination prevents large result sets from overwhelming clients and servers. Implement cursor-based pagination for real-time data that changes frequently, using opaque cursors that encode the position in the result set: /users?cursor=eyJpZCI6MTIzfQ. Use offset-based pagination for stable datasets where users need to jump to specific pages: /users?offset=100&limit=20. Return pagination metadata in responses, including total count, next/previous page URLs, and current position.

Filtering, sorting, and field selection allow clients to request exactly the data they need, reducing bandwidth and processing time. Support common filtering operations through query parameters: /products?category=electronics&price_min=100&price_max=500. Allow sorting with parameters like sort=price:asc,created_at:desc. Implement field selection to let clients specify which fields to include: /users?fields=id,name,email, reducing payload size significantly for resources with many fields.

Leverage HTTP caching to reduce server load and improve response times. Set appropriate Cache-Control headers for responses that can be cached: Cache-Control: max-age=3600 for data that changes infrequently. Use ETags for conditional requests—clients send the ETag from previous responses in If-None-Match headers, and servers return 304 Not Modified when content hasn't changed, eliminating unnecessary data transfer. Implement Last-Modified headers and If-Modified-Since for time-based caching strategies.

Compression reduces bandwidth usage and improves response times, especially for large payloads. Enable gzip or brotli compression for response bodies, which can reduce payload sizes by 70-90% for JSON responses. Most HTTP clients handle compression automatically, making this an easy win with minimal implementation effort. Balance compression level against CPU usage—medium compression levels provide most of the benefit with reasonable CPU costs.

Implementing Efficient Database Queries

Database queries often represent the primary performance bottleneck in APIs. Implement proper indexing on fields used in WHERE clauses, JOIN conditions, and ORDER BY statements. Monitor query performance and use database profiling tools to identify slow queries. Avoid N+1 query problems by using eager loading or batch loading strategies—fetching related resources in a single query rather than issuing separate queries for each item in a collection.

Consider implementing caching layers like Redis or Memcached for frequently accessed data that doesn't change often. Cache computed results, aggregations, and data from expensive queries. Implement cache invalidation strategies that balance staleness tolerance with cache hit rates. Use cache-aside patterns where applications check the cache first and fall back to the database on cache misses, updating the cache with retrieved data.

Implement asynchronous processing for long-running operations that don't need to complete before responding to clients. Accept the request, queue it for background processing, and return 202 Accepted with a status endpoint where clients can check progress. This approach keeps APIs responsive while handling expensive operations like report generation, data import, or complex calculations. Provide webhooks or polling mechanisms for clients to receive notifications when operations complete.

Documentation and Developer Experience

Even the most well-designed API fails if developers cannot understand how to use it. Comprehensive, accurate, and accessible documentation transforms your API from a technical interface into a product that developers enjoy using. Documentation should serve both as a reference for experienced developers and as a tutorial for newcomers, providing multiple entry points for different learning styles and use cases.

Start with a getting started guide that walks developers through their first API call in minutes. Include authentication setup, a simple example request, and expected response. Provide code samples in multiple popular languages, showing not just the HTTP request but complete, runnable examples using common libraries. Explain common pitfalls and how to avoid them, reducing the frustration of first-time integration attempts.

Document every endpoint with complete information about URL patterns, supported HTTP methods, required and optional parameters, request body schemas, response formats, possible status codes, and example requests and responses. Use OpenAPI (formerly Swagger) specifications to create machine-readable documentation that can generate interactive documentation, client libraries, and testing tools automatically. Keep documentation synchronized with implementation—outdated documentation is worse than no documentation because it erodes trust.

- ✨ Interactive documentation that lets developers try API calls directly from the browser, seeing real responses without writing code

- 🔍 Search functionality that helps developers quickly find relevant endpoints and information across extensive documentation

- 📱 Code examples in multiple languages showing real-world usage patterns, not just theoretical syntax

- ⚡ Error handling guides that explain common errors, their causes, and step-by-step resolution procedures

- 🎯 Use case tutorials that demonstrate how to combine multiple endpoints to accomplish common tasks

Providing Developer Support Resources

Documentation alone isn't sufficient—developers need channels for asking questions, reporting issues, and sharing knowledge. Establish a developer forum or community where developers can help each other, creating a knowledge base that grows organically. Monitor these channels actively, responding quickly to questions and using feedback to improve documentation and identify API pain points.

Publish SDKs and client libraries for popular programming languages, abstracting away HTTP details and providing idiomatic interfaces that feel natural in each language. Include comprehensive examples and maintain these libraries with the same rigor as your API itself. Open-source these libraries when possible, allowing the community to contribute improvements and fix issues.

"Documentation is not a chore to complete after building an API—it's an integral part of the product that deserves the same attention to detail, user experience design, and continuous improvement as the API itself."

Maintain a changelog that documents all API changes, from new features to bug fixes to deprecations. Use semantic versioning principles to communicate the impact of changes clearly. Announce significant changes through multiple channels—email lists, blog posts, and in-product notifications—giving developers adequate notice to prepare for changes that affect their integrations.

Monitoring and Observability

You cannot improve what you don't measure. Comprehensive monitoring and observability provide visibility into how your API performs in production, how developers use it, and where problems occur. This information drives optimization efforts, informs capacity planning, and enables rapid incident response when issues arise. Implement monitoring from day one rather than waiting until problems force you to add it retroactively.

Track key performance metrics including request rate, response time percentiles (p50, p95, p99), error rates by status code, and endpoint-level metrics. Monitor infrastructure metrics like CPU usage, memory consumption, database connection pool sizes, and queue depths. Set up alerting thresholds that notify operations teams when metrics exceed acceptable ranges, enabling proactive problem resolution before users are significantly impacted.

Implement distributed tracing to follow requests through your entire system, from API gateway through application servers to databases and external services. Tools like OpenTelemetry provide standardized instrumentation that captures timing information, errors, and context at each step. Distributed tracing proves invaluable for diagnosing performance problems in complex systems where a single API call triggers dozens of internal operations.

Collect and analyze logs from all API components, centralizing them in a searchable system. Structure logs as JSON for easy parsing and analysis. Include correlation IDs that link all log entries related to a single request, making it easy to reconstruct the complete request flow when investigating issues. Implement appropriate log levels—debug, info, warning, error—and adjust logging verbosity based on environment and current troubleshooting needs.

Analyzing Usage Patterns

Beyond operational metrics, analyze how developers use your API to inform product decisions and identify opportunities for improvement. Track which endpoints receive the most traffic, which features go unused, and where developers encounter errors most frequently. Identify common request patterns that might benefit from optimization or new convenience endpoints that combine multiple operations.

Monitor API adoption metrics including new developer registrations, first successful API call time, active integrations, and retention rates. Track the developer journey from documentation access through authentication setup to first successful request, identifying friction points where developers abandon integration attempts. Use this data to prioritize documentation improvements, SDK enhancements, and API design changes that reduce integration complexity.

Implement error tracking that groups similar errors together and provides context about affected users, frequency, and trends over time. Prioritize fixing errors that affect many users or that have increased significantly in recent deployments. Provide developers with request IDs they can include when reporting problems, allowing support teams to quickly locate relevant logs and traces for debugging.

Testing Strategies for API Reliability

Comprehensive testing ensures your API behaves correctly under all conditions, from happy path scenarios to edge cases and error conditions. Testing catches bugs before they reach production, provides confidence when making changes, and serves as executable documentation of expected behavior. Implement multiple testing layers, each serving different purposes and providing different types of confidence in your system's correctness.

Unit tests verify individual components in isolation, testing business logic, validation rules, and data transformations. Mock external dependencies like databases and third-party services to make tests fast and reliable. Unit tests should run in seconds, enabling rapid feedback during development. Aim for high code coverage but focus on testing important logic rather than chasing coverage percentages—100% coverage of trivial code provides little value.

Integration tests verify that components work together correctly, testing against real databases and external services in controlled environments. Integration tests catch issues that unit tests miss, like incorrect SQL queries, serialization problems, or misconfigured dependencies. Run integration tests as part of continuous integration pipelines, ensuring that changes don't break component interactions.

Contract tests ensure API responses match documented schemas and maintain backward compatibility. Tools like Pact allow you to define contracts between API providers and consumers, automatically verifying that changes don't break existing clients. Contract testing proves especially valuable in microservices architectures where multiple teams develop interdependent services independently.

End-to-end tests simulate real user workflows, testing complete scenarios from authentication through business operations to data persistence. While slower and more fragile than other test types, end-to-end tests provide confidence that the entire system works together correctly. Focus end-to-end tests on critical user journeys rather than attempting comprehensive coverage—maintain just enough tests to catch major integration issues.

Performance and Load Testing

Functional correctness alone doesn't guarantee production readiness—your API must also perform adequately under expected load and degrade gracefully when overloaded. Implement performance tests that measure response times under realistic load, identifying performance regressions before they reach production. Establish performance budgets for critical endpoints and fail builds that exceed these budgets, making performance a first-class concern.

Conduct load testing to verify your system handles expected traffic volumes. Gradually increase load while monitoring response times, error rates, and resource utilization. Identify the breaking point where your system becomes overloaded and understand failure modes—does it degrade gracefully, returning errors quickly, or does it hang, consuming resources without making progress? Use load testing results to inform capacity planning and identify optimization opportunities.

Perform chaos engineering experiments that deliberately introduce failures to verify your system's resilience. Simulate database outages, network partitions, slow external services, and resource exhaustion. Verify that circuit breakers trip appropriately, retries work correctly, and the system recovers gracefully when failures resolve. Chaos engineering builds confidence that your system handles real-world failures that inevitably occur in production.

Evolving Your API Over Time

APIs are never truly finished—they evolve continuously as business requirements change, technology improves, and you learn from production experience. Successful API evolution balances innovation with stability, introducing improvements without breaking existing integrations. Establish processes for gathering feedback, prioritizing changes, and implementing improvements in a controlled, predictable manner.

Gather developer feedback through multiple channels. Monitor support tickets and forum discussions for recurring pain points. Conduct developer surveys to understand satisfaction levels and gather feature requests. Analyze API usage patterns to identify unexpected usage that might indicate missing features or confusing documentation. Engage directly with high-value integrators to understand their needs and challenges deeply.

Establish a change management process that evaluates proposed changes for their impact on existing integrations. Categorize changes as additive, compatible, or breaking. Additive changes can be deployed immediately. Compatible changes require documentation updates but don't break existing clients. Breaking changes require new API versions and careful migration planning. Use this categorization to make informed decisions about when and how to introduce changes.

Implement feature flags that allow you to deploy new functionality gradually, testing it with internal users or a small percentage of traffic before full rollout. Feature flags enable quick rollback if problems emerge and facilitate A/B testing of different API designs. Use feature flags judiciously—too many flags increase complexity and make code harder to understand.

Maintain internal API standards that codify design decisions and ensure consistency as your API grows. Document conventions for naming, error handling, pagination, filtering, and other common patterns. Review new endpoints against these standards before deployment, preventing drift and maintaining the cohesive developer experience that makes APIs pleasant to use. Update standards as you learn from experience, but do so deliberately and communicate changes clearly.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between REST and RESTful APIs?

REST (Representational State Transfer) is an architectural style defined by Roy Fielding, consisting of specific constraints like statelessness, client-server architecture, and uniform interface. A RESTful API is an implementation that adheres to these REST principles. In practice, many APIs claim to be RESTful while only partially following REST constraints. True RESTful APIs use HTTP methods semantically, represent resources through URLs, leverage hypermedia for discoverability, and maintain statelessness. Many modern APIs adopt REST principles pragmatically, implementing the aspects that provide clear benefits while relaxing others that add complexity without proportional value.

Should I use PUT or PATCH for updating resources?

Use PUT when clients send complete resource representations and want to replace the entire resource. PUT requires clients to include all fields, even those that haven't changed. Use PATCH when clients send partial updates containing only the fields that should change. PATCH is more efficient for large resources where clients typically modify only a few fields. However, PATCH is more complex to implement correctly, especially around validation and conflict handling. Many APIs support both methods, using PUT for full updates and PATCH for partial updates, giving clients flexibility to choose the appropriate method for their use case.

How should I handle API versioning in microservices architectures?

In microservices architectures, versioning becomes more complex because services evolve independently. Consider using semantic versioning at the service level, with major versions indicating breaking changes. Implement backward compatibility within major versions when possible, using techniques like optional fields and default values. Use API gateways to route requests to appropriate service versions based on client requirements. Implement consumer-driven contract testing to detect breaking changes before deployment. Consider whether you need global API versions that span multiple services or per-service versioning that allows independent evolution. The right approach depends on your organization's size, deployment practices, and client diversity.

What authentication method should I use for my API?

The appropriate authentication method depends on your use case. OAuth 2.0 works well for APIs accessed by third-party applications on behalf of users, providing delegated authorization without sharing credentials. JWT tokens work well for APIs accessed by your own applications, providing stateless authentication that scales easily. API keys work for server-to-server communication where you control both client and server. For public APIs with varying client types, support multiple authentication methods to accommodate different integration scenarios. Always use HTTPS regardless of authentication method, implement token expiration and refresh mechanisms, and provide clear documentation about authentication requirements and procedures.

How do I handle rate limiting fairly across different client types?

Implement tiered rate limiting based on client types or subscription levels. Free tier clients might receive lower limits while paying customers receive higher limits. Consider implementing different limits for different endpoints based on resource intensity—expensive operations like report generation warrant lower limits than simple read operations. Use token bucket or leaky bucket algorithms that allow brief bursts while maintaining average rate limits. Provide clear feedback through rate limit headers so clients can implement appropriate backoff strategies. Consider implementing quota systems for expensive operations separate from request rate limits, allowing clients to perform a certain number of costly operations per day regardless of overall request volume.

What is the best way to handle pagination for large datasets?

For datasets that change frequently or where you need consistent results across pages, use cursor-based pagination with opaque cursors that encode position. This approach handles insertions and deletions gracefully and performs efficiently even for deep pages. For stable datasets where users need random access to specific pages, offset-based pagination provides better user experience despite potential performance issues with large offsets. Consider implementing keyset pagination for time-ordered data, using the last item's timestamp as the cursor for the next page. Provide metadata including total count when feasible, but be aware that counting large result sets can be expensive. Allow clients to specify page size within reasonable bounds, balancing client needs with server resource constraints.