How to Design Scalable System Architecture

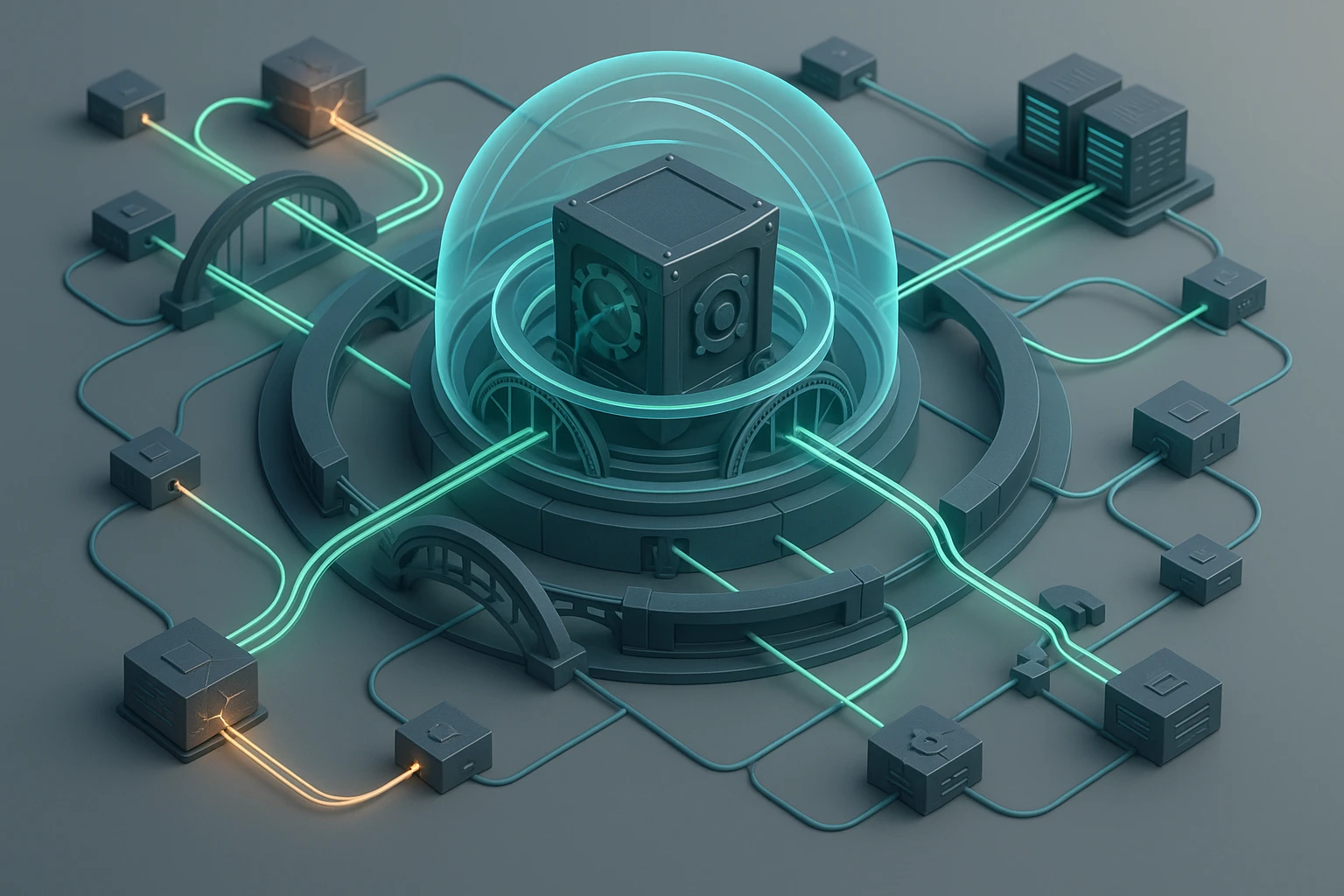

Scalable system diagram: load balancers, microservices, databases, cache, async queues, monitoring, autoscaling, secure APIs, redundancy and fault-tolerant distributed architecture

How to Design Scalable System Architecture

In today's rapidly evolving digital landscape, the ability to design systems that grow seamlessly with demand has become a fundamental requirement rather than a luxury. Organizations face mounting pressure as user bases expand exponentially, data volumes multiply, and service expectations intensify. The difference between systems that thrive under pressure and those that crumble often comes down to architectural decisions made during the design phase. When systems fail to scale, businesses lose revenue, reputation, and competitive advantage—sometimes irreversibly.

Scalable system architecture refers to the deliberate structuring of software and infrastructure components to handle increasing workloads without proportional increases in complexity or cost. This discipline encompasses multiple dimensions: horizontal and vertical scaling strategies, distributed computing principles, data management approaches, and resilience patterns. Throughout this exploration, we'll examine various perspectives—from infrastructure considerations to application design patterns, from theoretical foundations to practical implementation strategies.

By engaging with this comprehensive guide, you'll gain actionable insights into the fundamental principles that underpin scalable architectures, understand the trade-offs inherent in different approaches, and discover proven patterns used by leading technology organizations. Whether you're architecting a new system from scratch or refactoring an existing application, the frameworks and methodologies presented here will equip you with the knowledge to make informed decisions that align technical capabilities with business objectives.

Understanding the Foundations of Scalability

Before diving into specific techniques and patterns, establishing a solid conceptual foundation proves essential. Scalability exists along multiple axes, each presenting unique challenges and opportunities. The distinction between vertical and horizontal scaling represents perhaps the most fundamental concept in this domain.

Vertical scaling, often called "scaling up," involves adding more resources to existing infrastructure—increasing CPU capacity, memory, or storage on a single server. This approach offers simplicity in implementation and maintains application compatibility without architectural changes. However, it encounters hard physical limits and creates single points of failure. A database server can only accommodate so much RAM before hitting hardware constraints, and when that server fails, the entire system becomes unavailable.

Horizontal scaling, conversely, distributes workload across multiple machines—adding more servers rather than making individual servers more powerful. This "scaling out" approach provides virtually unlimited growth potential and inherent redundancy. If one server fails, others continue serving requests. The complexity lies in coordinating these distributed components, managing state across machines, and ensuring data consistency.

"The architecture decisions you make today will either enable or constrain your ability to scale tomorrow. Choose wisely, because refactoring at scale is exponentially more difficult than building correctly from the start."

Beyond these fundamental scaling dimensions, architects must consider performance scalability versus administrative scalability. Performance scalability addresses the system's ability to maintain response times and throughput as load increases. Administrative scalability concerns how easily teams can manage and maintain systems as they grow in complexity. A system might handle millions of requests per second yet become administratively unmanageable if it requires extensive manual intervention.

Defining Scalability Metrics and Goals

Effective scalability design begins with clear, measurable objectives. Vague aspirations like "handle more users" provide insufficient guidance for architectural decisions. Instead, establish specific targets:

- Throughput targets: Define requests per second, transactions per minute, or data processing volumes the system must sustain

- Latency requirements: Specify acceptable response times at various percentiles (p50, p95, p99) under different load conditions

- Concurrency levels: Determine simultaneous user sessions or concurrent operations the system must support

- Data volume projections: Estimate storage requirements over time, considering both operational data and historical archives

- Growth rate expectations: Project how quickly demand will increase—linear, exponential, or seasonal patterns

These metrics form the basis for capacity planning and architectural decisions. A system designed to scale from 10,000 to 100,000 users requires fundamentally different approaches than one targeting growth from 100,000 to 10 million users.

Architectural Patterns for Scalability

Successful scalable systems rely on proven architectural patterns that address common challenges. These patterns represent distilled wisdom from countless implementations, offering tested solutions to recurring problems.

Microservices Architecture

The microservices pattern decomposes applications into small, independently deployable services, each responsible for specific business capabilities. This architectural style enables teams to scale individual components based on their specific demands rather than scaling the entire application monolithically.

Each microservice operates as an autonomous unit with its own database, allowing teams to choose appropriate technologies for specific requirements. A recommendation engine might use a graph database while an inventory service uses a relational database. Services communicate through well-defined APIs, typically using REST over HTTP or message queues.

The benefits for scalability are substantial. When user authentication experiences high demand, only those services need additional instances. When payment processing requires more resources, those services scale independently. This granular scaling optimizes resource utilization and reduces costs compared to scaling entire monolithic applications.

However, microservices introduce complexity in distributed system management, network communication overhead, and data consistency challenges. Organizations must invest in robust DevOps practices, monitoring infrastructure, and service mesh technologies to realize these benefits effectively.

Event-Driven Architecture

Event-driven architectures decouple components through asynchronous message passing. Rather than direct service-to-service calls, components publish events to message brokers, and interested services subscribe to relevant event streams. This pattern provides exceptional scalability characteristics through natural load leveling and temporal decoupling.

When a user places an order, the order service publishes an "OrderPlaced" event. Inventory management, payment processing, shipping coordination, and analytics services all consume this event independently, processing it according to their own capacity and priorities. If the inventory service experiences temporary overload, events queue until capacity becomes available, preventing cascading failures.

"Asynchronous processing isn't just about performance—it's about building systems that gracefully handle the inevitable inconsistencies and delays inherent in distributed computing."

Event-driven systems excel at handling spiky workloads where demand fluctuates dramatically. Message queues act as buffers, absorbing traffic spikes and allowing backend services to process requests at sustainable rates. This buffering capability prevents system overload during peak periods while maintaining efficiency during normal operations.

CQRS and Event Sourcing

Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) separates read and write operations into distinct models. This separation allows independent scaling of read-heavy and write-heavy workloads, which often have dramatically different characteristics and requirements.

In traditional architectures, the same database model serves both reads and writes, forcing compromises that satisfy neither workload optimally. CQRS allows write models optimized for data consistency and business logic validation, while read models optimize for query performance and denormalization.

Event sourcing complements CQRS by storing state changes as a sequence of events rather than current state snapshots. Instead of updating a customer record directly, the system records "CustomerAddressChanged" events. Current state derives from replaying these events, providing complete audit trails and enabling temporal queries.

Together, these patterns enable powerful scalability strategies. Read models can be denormalized into various specialized databases—graph databases for relationship queries, search engines for full-text search, columnar stores for analytics—each optimized for specific query patterns. As read demand grows, additional read replicas scale horizontally without impacting write performance.

Database Scaling Strategies

Databases frequently become scalability bottlenecks in growing systems. Data persistence layers must maintain consistency, durability, and performance simultaneously—often competing objectives that require careful balancing.

Replication Approaches

Database replication distributes data across multiple servers, improving both availability and read scalability. Master-slave replication designates one primary database accepting writes, which then replicate to one or more read-only replicas. Applications direct read queries to replicas, distributing load and improving read throughput dramatically.

This approach works exceptionally well for read-heavy workloads where the read-to-write ratio exceeds 10:1. E-commerce product catalogs, content management systems, and social media feeds exemplify scenarios where replication provides immediate scalability benefits. However, replication introduces eventual consistency—replicas lag slightly behind the master, meaning recent writes might not immediately appear in read queries.

Master-master replication allows multiple databases to accept writes simultaneously, each replicating changes to others. This configuration eliminates single points of failure for writes and distributes write load geographically. The complexity increases substantially, as conflict resolution mechanisms must handle simultaneous updates to the same data across different masters.

Sharding and Partitioning

When data volumes exceed single-server capacity, sharding distributes data across multiple databases based on a partition key. Each shard contains a subset of total data, allowing the system to scale storage and throughput horizontally.

| Sharding Strategy | Description | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range-based | Partitions data by key ranges (A-M, N-Z) | Simple implementation, efficient range queries | Potential hotspots if data distribution is uneven |

| Hash-based | Uses hash function on partition key | Even distribution, prevents hotspots | Range queries require querying all shards |

| Geographic | Partitions by geographic region | Data locality reduces latency, regulatory compliance | Uneven growth across regions |

| Directory-based | Lookup table maps keys to shards | Flexible reassignment, custom logic | Lookup service becomes potential bottleneck |

Choosing the appropriate partition key proves critical. User ID works well for user-centric data, ensuring all information for a given user resides on one shard, enabling efficient queries without cross-shard joins. Temporal keys suit time-series data, allowing efficient archival of old shards while keeping recent data on high-performance storage.

Sharding introduces operational complexity. Cross-shard queries require aggregating results from multiple databases. Transactions spanning shards become difficult or impossible, often requiring eventual consistency and compensating transactions. Rebalancing shards as data grows requires careful planning and execution to avoid downtime.

"Sharding is a one-way door—once you commit to this path, returning to a single database becomes prohibitively expensive. Make this decision deliberately, with full awareness of the operational burden it creates."

NoSQL Database Considerations

NoSQL databases emerged specifically to address scalability limitations in traditional relational databases. Different NoSQL categories optimize for different use cases, and understanding these trade-offs enables appropriate technology selection.

Document databases like MongoDB store semi-structured data as JSON-like documents, providing flexible schemas that evolve without migrations. They scale horizontally through automatic sharding and offer strong query capabilities. Document databases suit content management, user profiles, and product catalogs where data naturally clusters around entities.

Key-value stores like Redis and DynamoDB provide the simplest data model—keys map to values—enabling exceptional performance and scalability. Their simplicity limits query capabilities but makes them ideal for caching, session storage, and scenarios requiring predictable, low-latency access patterns.

Column-family stores like Cassandra organize data into column families, optimizing for write-heavy workloads and time-series data. They excel at ingesting massive data volumes and provide tunable consistency levels, allowing applications to balance consistency requirements against performance needs.

Graph databases like Neo4j specialize in relationship-heavy data, providing efficient traversal of connected entities. Social networks, recommendation engines, and fraud detection systems benefit from graph databases' ability to query complex relationship patterns efficiently.

Caching Strategies for Performance at Scale

Caching represents one of the most effective techniques for improving scalability, reducing load on backend systems by serving frequently accessed data from high-speed storage. Strategic caching implementation can reduce database load by 80-95%, dramatically improving response times and system capacity.

Cache Placement Patterns

🔹 Client-side caching stores data in browsers or mobile applications, eliminating network requests entirely for cached content. HTTP cache headers control browser behavior, specifying how long resources remain valid. This approach works excellently for static assets like images, stylesheets, and JavaScript files, but requires careful cache invalidation strategies for dynamic content.

🔹 CDN caching distributes content across geographically dispersed edge servers, serving users from nearby locations to minimize latency. CDNs excel at delivering static content globally but increasingly support dynamic content through edge computing capabilities. Proper cache key design and purge strategies ensure content freshness while maximizing cache hit rates.

🔹 Application-level caching places cache layers between applications and databases, typically using in-memory stores like Redis or Memcached. This pattern provides the greatest control over caching logic, allowing sophisticated strategies like cache warming, selective invalidation, and multi-tier caching hierarchies.

🔹 Database query caching stores query results within the database system itself, transparently serving repeated queries from cache. While convenient, this approach offers less control than application-level caching and doesn't reduce database connections or computational load for cache misses.

Cache Invalidation Strategies

The challenge in caching lies not in storing data but in maintaining consistency as underlying data changes. Several strategies address this fundamental problem, each with distinct trade-offs.

"There are only two hard problems in computer science: cache invalidation and naming things. Of these, cache invalidation causes more production incidents."

Time-based expiration (TTL) sets expiration times on cached entries, after which the cache automatically discards them. This simple approach works well when data changes predictably or when eventual consistency is acceptable. Setting appropriate TTL values requires balancing freshness requirements against cache hit rates—shorter TTLs provide fresher data but reduce cache effectiveness.

Event-based invalidation actively removes or updates cache entries when underlying data changes. When a product price updates, the system explicitly invalidates cached product data, ensuring subsequent requests fetch fresh information. This approach provides strong consistency but requires careful coordination between write operations and cache management, increasing system complexity.

Write-through caching updates both cache and database simultaneously during write operations, maintaining consistency at the cost of write latency. Write-behind caching updates the cache immediately and asynchronously persists to the database, improving write performance but risking data loss if cache failures occur before persistence completes.

Cache Warming and Preloading

Cold cache scenarios—when caches are empty after deployment or failure—can overwhelm backend systems as all requests bypass the cache simultaneously. Cache warming proactively populates caches before directing traffic, preventing this "thundering herd" problem.

Sophisticated systems analyze access patterns to predict which data will be requested, preloading those entries during off-peak hours. Machine learning models can identify temporal patterns—certain products trend on specific days, user activity spikes at particular times—enabling intelligent preloading that maximizes cache effectiveness.

Load Balancing and Traffic Management

Distributing incoming requests across multiple servers prevents any single instance from becoming overwhelmed while ensuring high availability. Load balancers operate at various network layers, each offering different capabilities and trade-offs.

Load Balancing Algorithms

Round-robin distribution cycles through available servers sequentially, providing simple, even distribution when all servers have equivalent capacity and all requests require similar processing. This algorithm's simplicity makes it reliable but ignores server load differences and request complexity variations.

Least connections directs traffic to servers handling the fewest active connections, accounting for varying request durations. Long-running requests naturally accumulate on specific servers, and this algorithm prevents overloading those instances while others sit idle. This approach works particularly well for applications with highly variable request processing times.

Weighted distribution assigns different proportions of traffic based on server capacity. A server with twice the CPU and memory receives twice the traffic of smaller instances, optimizing resource utilization across heterogeneous infrastructure. This flexibility supports gradual rollouts, where new server versions initially receive small traffic percentages, increasing as confidence grows.

IP hash-based routing consistently routes requests from the same client IP to the same server, providing session affinity without server-side session storage. This approach simplifies application design but can create uneven load distribution when traffic originates from a small number of IP addresses, such as corporate proxies.

Health Checks and Failure Detection

Effective load balancing requires accurate health monitoring to remove failed instances from rotation automatically. Passive health checks monitor response codes and timeouts during normal traffic flow, marking servers unhealthy after consecutive failures. Active health checks periodically send synthetic requests to dedicated health endpoints, verifying server readiness even during low traffic periods.

Health check design significantly impacts system reliability. Superficial checks that merely verify the application responds miss deeper issues like database connectivity problems or resource exhaustion. Comprehensive health checks validate critical dependencies while remaining lightweight enough to run frequently without impacting performance.

| Health Check Type | What It Validates | Response Time | Resource Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shallow | Application responds to requests | < 10ms | Minimal |

| Moderate | Database connectivity, critical services reachable | 50-100ms | Low |

| Deep | End-to-end functionality, all dependencies healthy | 200-500ms | Moderate |

| Comprehensive | Full system capabilities, data consistency | > 500ms | High |

Balancing check frequency against resource consumption requires careful tuning. Frequent checks detect failures quickly but consume bandwidth and CPU. Infrequent checks reduce overhead but delay failure detection, potentially routing traffic to unhealthy instances longer.

Geographic Distribution and Edge Computing

Global user bases demand geographically distributed infrastructure to minimize latency. Multi-region deployments place application servers near user concentrations, reducing network round-trip times from hundreds of milliseconds to tens of milliseconds—improvements users perceive as dramatically faster experiences.

Geographic load balancing routes users to the nearest healthy region based on latency measurements or geographic proximity. When regional failures occur, traffic automatically redirects to alternative regions, maintaining availability despite localized outages.

Edge computing extends this concept further, executing application logic on edge servers distributed globally. Rather than merely caching static content, edge platforms run serverless functions that personalize responses, aggregate data from multiple sources, and implement business logic close to users. This architecture minimizes latency for dynamic content while reducing load on centralized infrastructure.

"Latency is the enemy of user experience. Every millisecond of delay measurably impacts conversion rates, engagement, and user satisfaction. Geographic distribution isn't optional for global applications—it's essential."

Asynchronous Processing and Message Queues

Synchronous request-response patterns create tight coupling between components, forcing users to wait for all processing to complete before receiving responses. Asynchronous processing decouples operations, allowing immediate user feedback while background workers handle time-consuming tasks.

When users upload images, synchronous processing would resize images, generate thumbnails, extract metadata, and update search indexes before responding—potentially taking seconds. Asynchronous processing immediately confirms upload success, queuing background jobs for subsequent processing. Users receive instant feedback while the system processes images at its own pace.

Message Queue Patterns

Point-to-point queues deliver each message to exactly one consumer, ensuring work distribution across multiple workers. When processing orders, multiple worker instances consume from the order queue, each handling different orders concurrently. This pattern scales processing capacity horizontally—adding workers increases throughput proportionally.

Publish-subscribe patterns deliver each message to multiple subscribers, enabling event-driven architectures where multiple services react to the same event independently. When users register, the authentication service publishes a "UserRegistered" event. Email services send welcome messages, analytics services track conversion funnels, and CRM systems create customer records—all triggered by the same event without explicit coordination.

Priority queues process messages based on importance rather than arrival order, ensuring critical operations receive preferential treatment. Premium user requests might bypass standard queues, or time-sensitive operations like password resets could take precedence over batch reporting jobs.

Backpressure and Flow Control

Message queues buffer work during traffic spikes, but unbounded queues eventually exhaust memory or storage. Backpressure mechanisms prevent queue overflow by signaling upstream components to slow down when downstream capacity is saturated.

Implementing backpressure requires careful design. Rejecting requests outright provides clear feedback but degrades user experience. Rate limiting spreads requests over time, smoothing traffic spikes while maintaining system stability. Circuit breakers detect sustained overload and temporarily reject requests, preventing cascading failures while giving systems time to recover.

Queue depth monitoring provides early warning of capacity issues. Gradually increasing queue depths indicate processing capacity insufficient for incoming load, signaling the need for additional workers or infrastructure scaling. Sudden queue depth spikes might indicate downstream service degradation requiring investigation.

Dead Letter Queues and Error Handling

Not all messages process successfully. Transient failures—temporary network issues, brief service unavailability—warrant retry attempts. Permanent failures—malformed data, business logic violations—require different handling to prevent infinite retry loops.

Dead letter queues capture messages that repeatedly fail processing, removing them from primary queues after exhausting retry attempts. These failed messages require human investigation or specialized error handling logic. Monitoring dead letter queue growth reveals systematic issues requiring code fixes or data corrections.

Retry strategies significantly impact system behavior. Immediate retries might overwhelm already-struggling services, exacerbating problems. Exponential backoff delays retries progressively—waiting 1 second, then 2, then 4—giving systems time to recover while eventually succeeding for transient failures.

"Asynchronous processing is not just about performance—it's about building resilient systems that gracefully degrade under pressure rather than collapsing catastrophically."

Monitoring, Observability, and Performance Optimization

Scalable systems require comprehensive monitoring to understand behavior under varying loads, identify bottlenecks before they impact users, and validate that scaling strategies achieve intended results. Observability extends beyond simple metrics, providing deep insights into system internals through logs, metrics, and distributed traces.

Key Metrics for Scalability

🔹 Throughput metrics measure requests per second, transactions per minute, or data processing rates, indicating overall system capacity. Tracking throughput trends reveals whether systems scale linearly with added resources or encounter diminishing returns suggesting architectural bottlenecks.

🔹 Latency percentiles capture response time distribution, with p95 and p99 percentiles revealing worst-case user experiences. Average response times mask outliers—a system averaging 100ms might have p99 latencies exceeding 5 seconds, creating poor experiences for a significant user subset. Percentile targets ensure consistently good performance rather than merely acceptable averages.

🔹 Error rates track failed requests as percentages of total traffic, with granular breakdowns by error type revealing specific failure modes. Sudden error rate spikes indicate deployments introducing bugs or infrastructure failures requiring immediate attention. Gradual increases might suggest capacity exhaustion or degrading dependencies.

🔹 Resource utilization monitors CPU, memory, disk, and network consumption across infrastructure, identifying resources approaching capacity limits before they impact performance. Unbalanced utilization—high CPU with low memory usage—suggests opportunities for optimization or resource reallocation.

🔹 Saturation metrics measure queue depths, connection pool utilization, and thread pool occupancy, indicating how close systems operate to capacity limits. These leading indicators predict performance degradation before it becomes visible to users, enabling proactive scaling.

Distributed Tracing

Microservices architectures distribute request processing across numerous services, making performance analysis challenging. Distributed tracing instruments requests with unique identifiers propagated across service boundaries, reconstructing complete request paths through complex systems.

When users report slow page loads, distributed traces reveal which services contributed latency. Perhaps database queries consumed 2 seconds, external API calls added 500ms, and internal processing required 300ms. This visibility pinpoints optimization opportunities—caching database results, parallelizing API calls, or optimizing algorithms.

Tracing also exposes unexpected dependencies and communication patterns. Services might make redundant calls to the same downstream service, or request chains might form circular dependencies. Visualizing these patterns through service dependency graphs reveals architectural improvements.

Capacity Planning and Load Testing

Proactive capacity planning prevents performance surprises during traffic spikes. Load testing simulates expected traffic patterns, revealing system behavior under stress and validating scaling strategies before production deployment.

Effective load tests gradually increase traffic while monitoring system metrics, identifying the point where performance degrades or errors emerge. This breaking point establishes current capacity limits, informing decisions about when to add resources. Testing should simulate realistic traffic patterns—gradual ramps, sudden spikes, sustained high load—as systems behave differently under various conditions.

Chaos engineering takes testing further by deliberately introducing failures—terminating servers, inducing network latency, exhausting resources—validating that systems handle failures gracefully. These experiments build confidence in resilience mechanisms and reveal weaknesses before real failures expose them.

Security Considerations in Scalable Architectures

Scalability and security often exist in tension. Security measures like encryption, authentication, and authorization add computational overhead, potentially limiting throughput. However, neglecting security in pursuit of performance creates vulnerabilities that attackers exploit, ultimately impacting availability and scalability.

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) Protection

Scalable systems attract DDoS attacks attempting to overwhelm infrastructure with malicious traffic. Multi-layered defense strategies distribute protection across network, application, and infrastructure layers.

Network-level protection filters obviously malicious traffic—packets with spoofed source addresses, excessive traffic from single sources—before reaching application servers. Content delivery networks and specialized DDoS mitigation services absorb attack traffic, leveraging massive infrastructure that dwarfs attacker capabilities.

Application-level protection implements rate limiting, requiring authentication for resource-intensive operations, and employing CAPTCHA challenges when suspicious patterns emerge. These measures prevent application-layer attacks that mimic legitimate traffic, bypassing network-level filters.

Authentication and Authorization at Scale

Traditional session-based authentication stores user sessions in server memory, creating stateful systems that complicate horizontal scaling. Stateless authentication using JSON Web Tokens (JWT) embeds user identity and permissions in cryptographically signed tokens, eliminating server-side session storage.

Clients include tokens with each request, allowing any server to validate authenticity without consulting centralized session stores. This approach scales horizontally without session replication complexity. However, token revocation becomes challenging—compromised tokens remain valid until expiration, requiring short expiration times and refresh token mechanisms.

API gateways centralize authentication and authorization, validating credentials before routing requests to backend services. This pattern simplifies security implementation, as individual services trust gateway-validated requests without redundant authentication logic. Gateways also enforce rate limiting, quota management, and threat detection consistently across all services.

Data Encryption and Compliance

Encryption protects data confidentiality but introduces performance overhead. Transport encryption (TLS) secures data in transit, adding latency for handshake negotiation and CPU load for encryption/decryption. Modern hardware acceleration and protocol improvements (TLS 1.3) minimize these costs, making encryption overhead acceptable for most applications.

At-rest encryption protects stored data from unauthorized access, essential for regulatory compliance. Database-level encryption transparently encrypts data before writing to disk, with minimal performance impact. Application-level encryption provides granular control, encrypting sensitive fields while leaving non-sensitive data unencrypted for performance.

Compliance requirements like GDPR or HIPAA impose data residency restrictions, requiring data remain within specific geographic regions. Multi-region architectures must carefully route and store data according to these regulations, often maintaining separate data stores per region to ensure compliance.

Cost Optimization in Scalable Systems

Scalability enables handling increased load, but uncontrolled scaling can lead to unsustainable costs. Efficient architectures balance performance requirements against infrastructure expenses, optimizing resource utilization without compromising user experience.

Auto-scaling Strategies

Auto-scaling dynamically adjusts infrastructure capacity based on demand, adding resources during traffic peaks and removing them during quiet periods. This approach optimizes costs by provisioning capacity only when needed rather than maintaining peak capacity constantly.

Reactive auto-scaling responds to current metrics—when CPU utilization exceeds 70%, add servers; when it drops below 30%, remove servers. This approach works well for gradual load changes but lags during sudden spikes, as new instances require minutes to provision and initialize.

Predictive auto-scaling analyzes historical patterns to anticipate demand, pre-provisioning capacity before traffic arrives. E-commerce sites scale up before daily peak shopping hours, and content platforms add capacity before scheduled content releases. Machine learning models identify complex patterns—weekly cycles, seasonal trends, special events—enabling accurate predictions.

Scheduled auto-scaling adjusts capacity based on known patterns, scaling up during business hours and down overnight. While less sophisticated than predictive approaches, scheduled scaling provides predictable cost management for applications with regular traffic patterns.

Resource Right-Sizing

Over-provisioned resources waste money, while under-provisioned systems suffer performance degradation. Right-sizing matches resource allocation to actual requirements through continuous monitoring and adjustment.

Many applications run on instance types far larger than necessary, paying for unused CPU, memory, or storage. Detailed utilization analysis reveals opportunities to downsize instances, potentially reducing costs by 40-60% without impacting performance. Conversely, some workloads benefit from larger instances with better price-performance ratios, as fewer large instances cost less than many small ones.

Serverless architectures take right-sizing to the extreme, charging only for actual compute time consumed. Functions execute in response to events, scaling automatically from zero to thousands of concurrent executions. This model eliminates idle capacity costs but introduces cold start latency and requires different development patterns.

Storage Optimization

Storage costs accumulate as data volumes grow, often exceeding compute costs in data-intensive applications. Tiered storage strategies optimize costs by storing data on appropriate media based on access patterns.

Hot data—frequently accessed information—resides on high-performance SSD storage despite higher costs. Warm data—occasionally accessed—moves to standard storage with balanced cost and performance. Cold data—rarely accessed archives—transfers to low-cost object storage or archival services, accepting higher retrieval latency for substantial cost savings.

Automated lifecycle policies transition data between tiers based on age and access patterns, optimizing costs without manual intervention. Compression reduces storage requirements, particularly for text and log data where compression ratios of 5:1 or better are common.

"The most expensive architecture is one that doesn't scale when you need it. The second most expensive is one that scales beyond what you need. Finding the balance requires constant monitoring and adjustment."

Emerging Trends and Future Considerations

Scalable architecture continues evolving as new technologies emerge and existing patterns mature. Understanding these trends helps architects design systems that remain relevant and maintainable over years of operation.

Serverless and Function-as-a-Service

Serverless computing abstracts infrastructure management entirely, allowing developers to focus purely on business logic. Functions execute in response to events, with cloud providers handling scaling, availability, and resource allocation automatically. This model provides infinite scalability—functions scale from zero to thousands of concurrent executions without configuration.

Serverless excels for event-driven workloads, API backends, and data processing pipelines where traffic varies significantly. The pay-per-execution model eliminates costs during idle periods, making serverless extremely cost-effective for sporadic workloads. However, cold starts introduce latency for infrequently invoked functions, and vendor lock-in concerns arise from proprietary APIs.

Edge Computing and 5G

Edge computing processes data closer to sources and consumers, reducing latency and bandwidth consumption. As 5G networks proliferate, edge computing becomes increasingly viable for latency-sensitive applications like autonomous vehicles, augmented reality, and IoT systems.

Distributed edge architectures challenge traditional centralized thinking, requiring new patterns for data synchronization, consistency management, and orchestration across thousands of edge locations. Applications must handle intermittent connectivity and operate autonomously when network partitions occur.

AI and Machine Learning Integration

Machine learning models increasingly influence scalability decisions, predicting traffic patterns for auto-scaling, detecting anomalies indicating attacks or failures, and optimizing resource allocation. These intelligent systems adapt to changing conditions more effectively than static rules, continuously improving through feedback loops.

However, ML model serving introduces its own scalability challenges. Models require significant computational resources, particularly for real-time inference on large inputs. Specialized hardware accelerators, model optimization techniques, and caching strategies address these challenges while maintaining prediction accuracy.

Multi-Cloud and Hybrid Architectures

Organizations increasingly adopt multi-cloud strategies, distributing workloads across multiple cloud providers to avoid vendor lock-in, optimize costs, and improve resilience. This approach introduces complexity in deployment orchestration, data synchronization, and security management across heterogeneous environments.

Hybrid architectures combine on-premises infrastructure with cloud resources, supporting regulatory requirements, leveraging existing investments, and enabling gradual cloud migration. These environments require sophisticated networking, identity management, and workload orchestration to function cohesively.

What is the difference between scalability and performance?

Performance measures how quickly a system processes individual requests, typically expressed as response time or latency. Scalability describes the system's ability to maintain that performance as load increases, whether by handling more concurrent users, processing larger data volumes, or serving more requests per second. A system can be performant at low load but fail to scale, or scale well while maintaining mediocre performance. Ideally, systems achieve both good performance and effective scalability, maintaining acceptable response times as demand grows.

When should I choose horizontal scaling over vertical scaling?

Horizontal scaling becomes preferable when workloads can be distributed across multiple machines, when high availability requirements demand redundancy, or when growth projections exceed single-machine capacity limits. Vertical scaling suits applications with tight data consistency requirements, complex inter-process communication needs, or when operational simplicity outweighs scalability requirements. Many systems employ hybrid approaches—vertically scaling to reasonable limits before adding horizontal scaling for further growth. Consider horizontal scaling when your architecture naturally partitions (stateless web servers, sharded databases) and vertical scaling for components requiring strong consistency or complex coordination.

How do I determine the right caching strategy for my application?

Caching strategy selection depends on data characteristics and consistency requirements. For data that changes infrequently and where eventual consistency is acceptable, aggressive caching with longer TTLs maximizes performance benefits. Frequently changing data requires shorter TTLs or event-based invalidation to maintain freshness. Critical data requiring strong consistency might bypass caching entirely or use write-through patterns. Analyze access patterns to identify hot data—frequently accessed items—and cache those while allowing cold data to hit databases. Monitor cache hit rates and adjust strategies iteratively, as application usage patterns evolve over time.

What are the most common scalability bottlenecks and how do I identify them?

Database operations frequently become bottlenecks, manifesting as slow query times, high connection pool utilization, or CPU saturation on database servers. Network bandwidth limitations appear as high latency despite low CPU usage, particularly in data-intensive applications. Synchronous processing creates bottlenecks when operations wait for external services or long-running computations. Stateful session management prevents horizontal scaling by tying users to specific servers. Identify bottlenecks through comprehensive monitoring—track response times, resource utilization, and queue depths across all system components. Load testing reveals bottlenecks by gradually increasing traffic until performance degrades, pinpointing the failing component.

How do microservices improve scalability compared to monolithic architectures?

Microservices enable independent scaling of individual components based on their specific resource requirements and traffic patterns. A monolithic application requires scaling the entire application even when only one feature experiences high demand, wasting resources on underutilized components. Microservices allow targeted scaling—adding capacity only where needed. They also enable independent deployment, allowing teams to update services without coordinating full application releases. However, microservices introduce complexity in distributed system management, inter-service communication, and data consistency that monolithic architectures avoid. The scalability benefits justify this complexity only when applications reach sufficient size and traffic that granular scaling provides meaningful advantages.

What role does database sharding play in scaling data-intensive applications?

Sharding distributes data across multiple database instances, allowing storage and throughput to scale horizontally beyond single-server limits. Each shard contains a subset of data, enabling parallel processing of queries and writes across multiple machines. This approach proves essential for applications where data volumes exceed terabytes or where write throughput surpasses single-database capacity. However, sharding introduces significant complexity—cross-shard queries require aggregating results from multiple databases, transactions spanning shards become difficult or impossible, and rebalancing data as shards grow requires careful planning. Consider sharding only when vertical scaling and read replicas prove insufficient, as the operational burden is substantial.