How to Implement API Caching Strategies

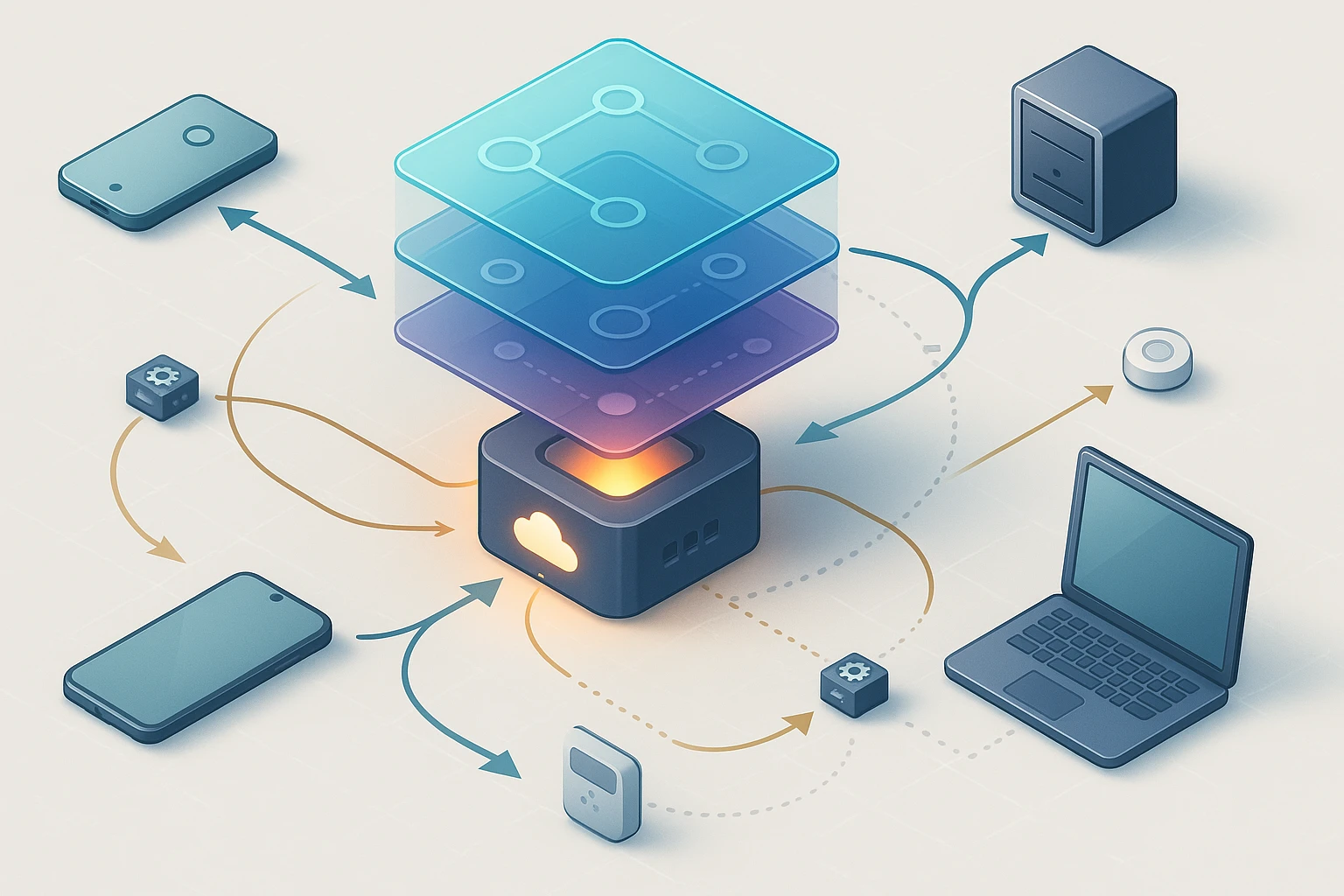

Diagram of API caching client, CDN, gateway, origin server, cache layers TTL, and invalidation, cache keys headers freshness indicators hit/miss stats latency reduction strategies.

How to Implement API Caching Strategies

Modern applications depend heavily on APIs to deliver data quickly and reliably to users across the globe. When your application makes repeated requests to the same endpoints, or when multiple users request identical information, your backend infrastructure can become overwhelmed, leading to slower response times, increased server costs, and a degraded user experience. The strategic implementation of caching mechanisms represents one of the most effective ways to address these challenges while simultaneously improving application performance and reducing operational expenses.

Caching involves storing frequently accessed data in a temporary storage layer that sits between your application and the original data source. This approach allows subsequent requests for the same information to be served from the cache rather than requiring a full round-trip to the database or external service. By understanding various caching strategies and their appropriate applications, developers can dramatically enhance their API's responsiveness while maintaining data accuracy and freshness.

Throughout this comprehensive guide, you'll discover practical approaches to implementing different caching layers, from browser-based solutions to distributed caching systems. You'll learn how to select appropriate cache invalidation strategies, configure cache headers correctly, and balance the trade-offs between performance gains and data consistency. Whether you're building a small application or scaling a large distributed system, these insights will help you make informed decisions about which caching strategies best serve your specific requirements.

Understanding the Fundamentals of API Caching

Before diving into implementation details, it's essential to grasp why caching matters and how it fundamentally changes the way your application handles data requests. Every API call typically involves multiple steps: the client sends a request across the network, the server processes it (often querying databases or calling other services), and finally returns a response. Each of these steps introduces latency, and when multiplied across thousands or millions of requests, these delays accumulate into significant performance bottlenecks.

Caching introduces an intermediate layer that stores copies of responses, allowing subsequent identical requests to be served almost instantaneously. This mechanism reduces the load on your backend systems, decreases response times from seconds or hundreds of milliseconds down to single-digit milliseconds, and can dramatically reduce your infrastructure costs. However, caching isn't a silver bullet—it introduces complexity around data freshness, storage management, and cache invalidation that requires careful consideration.

"The fastest API call is the one you never have to make. Proper caching transforms user experience by eliminating unnecessary network round-trips and database queries."

Different types of data require different caching approaches. Static content like images, stylesheets, and JavaScript files can be cached aggressively for extended periods. User-specific data requires more nuanced strategies that balance personalization with performance. Real-time data might need very short cache lifetimes or no caching at all. Understanding these distinctions helps you apply the right caching strategy to each endpoint in your API.

Key Caching Concepts and Terminology

Several fundamental concepts underpin all caching strategies. The cache hit occurs when requested data exists in the cache and can be served immediately, while a cache miss happens when the data isn't cached, requiring a full request to the origin server. The cache hit ratio—the percentage of requests served from cache—directly correlates with performance improvements and cost savings.

Time to Live (TTL) defines how long cached data remains valid before expiring. Setting appropriate TTL values requires balancing data freshness against cache effectiveness. Too short, and you lose performance benefits; too long, and users might see stale data. The cache key uniquely identifies cached items, typically derived from the request URL, query parameters, and sometimes headers like authentication tokens.

Cache invalidation refers to the process of removing or updating cached data when the underlying source changes. This represents one of the most challenging aspects of caching, as evidenced by the famous computer science saying about the two hardest problems: naming things, cache invalidation, and off-by-one errors.

Client-Side Caching Strategies

The first line of defense in any caching strategy begins at the client level, whether that's a web browser, mobile application, or API consumer. Client-side caching leverages storage mechanisms on the user's device to eliminate network requests entirely for cached resources. This approach delivers the fastest possible response times since data retrieval happens locally without any network latency.

HTTP Cache Headers Configuration

HTTP provides a sophisticated set of headers that control how clients and intermediary proxies cache responses. The Cache-Control header serves as the primary mechanism for defining caching behavior. Setting this header correctly can dramatically reduce server load while ensuring users receive fresh data when necessary.

For static resources that rarely change, you might use Cache-Control: public, max-age=31536000, immutable, which instructs browsers to cache the resource for one year and never revalidate it. The "immutable" directive tells browsers that the resource will never change, preventing unnecessary revalidation requests. This works particularly well when combined with versioned URLs or content hashing in filenames.

Dynamic content requires more nuanced approaches. The directive Cache-Control: private, max-age=300 caches responses for five minutes but only in the user's browser, preventing shared caches from storing potentially sensitive information. The "private" designation ensures that CDNs and proxy servers don't cache the response, making it suitable for personalized content.

For content that changes frequently but where some staleness is acceptable, consider Cache-Control: public, max-age=60, stale-while-revalidate=300. This configuration allows browsers to serve cached content for 60 seconds, then serve stale content for an additional 5 minutes while fetching fresh data in the background. This approach, called "stale-while-revalidate," provides excellent user experience by never blocking on cache revalidation.

"Properly configured cache headers represent the most cost-effective performance optimization available. They require no additional infrastructure and work automatically across all HTTP clients."

ETag and Conditional Requests

ETags (Entity Tags) provide a validation mechanism that allows clients to make conditional requests, avoiding full data transfers when content hasn't changed. The server generates a unique identifier (typically a hash) for each resource version and includes it in the ETag header. When the client makes subsequent requests, it includes this identifier in the If-None-Match header.

If the resource hasn't changed, the server responds with a 304 Not Modified status and no body, saving bandwidth while confirming the cached version remains valid. This approach works exceptionally well for resources that change unpredictably, as it eliminates the need to guess appropriate TTL values while still providing bandwidth savings.

Implementing ETag support in your API requires generating consistent identifiers for resources. For database-backed content, you might use a combination of the record's ID and last-modified timestamp. For computed content, a hash of the response body ensures accuracy. Many web frameworks provide automatic ETag generation, but custom implementations offer more control over the validation logic.

Local Storage and IndexedDB for Web Applications

Beyond HTTP caching, web applications can leverage browser storage APIs for more sophisticated caching strategies. localStorage provides simple key-value storage suitable for caching small amounts of data like user preferences or recent search queries. However, its synchronous API can block the main thread, making it unsuitable for large datasets.

IndexedDB offers a more powerful solution for caching substantial amounts of structured data. This asynchronous, NoSQL database allows storing complex objects, creating indexes, and performing efficient queries. Progressive Web Applications often use IndexedDB to cache API responses, enabling offline functionality and instant loading of previously viewed content.

When implementing client-side caching with these APIs, include metadata about when data was cached and implement your own expiration logic. Store timestamps alongside cached data and check them before using cached values. This approach gives you fine-grained control over data freshness while leveraging the performance benefits of local storage.

Server-Side Caching Approaches

While client-side caching reduces load for individual users, server-side caching strategies protect your backend infrastructure from repeated expensive operations. These approaches cache data at various points in your server architecture, from application-level memory caches to dedicated caching layers that serve multiple application instances.

In-Memory Caching with Redis and Memcached

In-memory data stores like Redis and Memcached provide extremely fast caching solutions by storing data in RAM rather than on disk. These systems can serve cached data in microseconds, making them ideal for high-traffic applications where every millisecond counts. Both solutions support distributed configurations, allowing multiple application servers to share a common cache.

Redis offers more features than Memcached, including data persistence, complex data structures (lists, sets, sorted sets), and pub/sub messaging. This versatility makes Redis suitable not just for caching but also for session storage, real-time analytics, and message queuing. However, this additional functionality comes with slightly higher memory overhead and complexity.

Memcached focuses exclusively on caching with a simpler architecture and slightly lower memory footprint per cached item. Its simplicity makes it easier to operate and reason about, particularly for straightforward caching use cases. Many high-traffic websites use Memcached to cache database query results, reducing database load by orders of magnitude.

When implementing in-memory caching, structure your cache keys carefully to avoid collisions and enable targeted invalidation. A common pattern uses prefixes to namespace different types of data: user:123:profile, product:456:details, search:keyword:results. This structure makes it easy to invalidate related items by pattern matching.

| Feature | Redis | Memcached |

|---|---|---|

| Data Structures | Strings, Lists, Sets, Sorted Sets, Hashes, Bitmaps, HyperLogLogs | Simple key-value pairs only |

| Persistence | Optional disk persistence with snapshots or append-only files | No persistence - purely in-memory |

| Replication | Master-slave replication with automatic failover | No built-in replication |

| Memory Usage | Slightly higher overhead per item | More memory-efficient for simple caching |

| Use Cases | Caching, session storage, real-time analytics, message queues | Pure caching scenarios, simple session storage |

| Scripting | Lua scripting support for complex operations | No scripting capabilities |

Application-Level Caching

Before reaching for external caching systems, consider application-level caching that stores data in your application's memory space. Most programming languages and frameworks provide built-in caching mechanisms that work well for single-server deployments or data that doesn't need sharing across instances.

In Node.js applications, simple object-based caches or libraries like node-cache provide lightweight solutions. Python developers often use functools.lru_cache decorator for function-level memoization or django.core.cache for framework-integrated caching. Java applications leverage solutions like Caffeine or Guava caches, which offer sophisticated eviction policies and automatic refresh capabilities.

Application-level caches excel at caching expensive computations, parsed configuration files, or frequently accessed reference data. Since this data resides in the application's memory, access times are measured in nanoseconds rather than milliseconds. However, this approach doesn't work well for distributed systems where multiple application instances need to share cached data.

"Application-level caching provides the fastest possible access times, but careful memory management is essential to prevent out-of-memory errors in production environments."

Database Query Result Caching

Database queries often represent the most expensive operations in API endpoints. Caching query results can transform response times from hundreds of milliseconds to single digits. This strategy works particularly well for read-heavy applications where the same queries execute repeatedly with identical parameters.

Implement query result caching by generating cache keys from the SQL query and its parameters. Before executing a query, check if results exist in your cache layer. On a cache hit, return the stored results immediately. On a cache miss, execute the query, store the results in cache with an appropriate TTL, then return them to the caller.

Many ORMs and database libraries provide built-in query caching. Django's ORM offers query result caching through its cache framework. SQLAlchemy supports query result caching through extensions. However, custom implementations often provide more control over cache key generation and invalidation strategies.

Be cautious with caching queries that include user-specific filters or authentication checks. Improperly cached queries can lead to data leaks where users see information they shouldn't access. Always include user identifiers in cache keys for personalized queries, or avoid caching them entirely if security concerns outweigh performance benefits.

CDN and Edge Caching

Content Delivery Networks distribute cached content across geographically dispersed servers, placing data physically closer to end users. This approach reduces latency by minimizing the distance data travels and offloads traffic from your origin servers. Edge caching represents the most scalable caching strategy, capable of handling massive traffic spikes without impacting your backend infrastructure.

Configuring CDN Caching Behavior

Modern CDNs like Cloudflare, Fastly, and AWS CloudFront provide sophisticated caching controls that respect your HTTP cache headers while offering additional configuration options. These platforms cache content at edge locations worldwide, serving requests from the nearest server to each user.

CDNs typically cache based on the full URL, including query parameters. This means /api/products?category=electronics and /api/products?category=books represent different cache entries. Some CDNs allow customizing which query parameters affect caching, enabling you to ignore tracking parameters while respecting functional ones.

Configure your CDN to cache different content types appropriately. Static assets like images, CSS, and JavaScript should be cached aggressively with long TTLs. API responses might use shorter TTLs or bypass edge caching entirely for dynamic content. Most CDNs allow setting cache behavior through configuration rules based on path patterns or file extensions.

Consider implementing cache warming strategies where you proactively populate CDN caches before traffic arrives. This approach works well for predictable traffic patterns, such as product launches or scheduled content releases. By requesting key URLs across multiple edge locations before users arrive, you ensure cache hits from the first request.

API Gateway Caching

API gateways like Kong, AWS API Gateway, or Azure API Management provide built-in caching capabilities that sit between clients and your backend services. This architectural layer offers centralized cache management, making it easier to implement consistent caching policies across multiple backend services.

Gateway caching works particularly well for microservices architectures where multiple services contribute to API responses. The gateway can cache aggregated responses, eliminating the need to call multiple services for frequently requested data. This reduces internal network traffic and improves response times while simplifying cache management.

Configure gateway caching with careful attention to authentication and authorization. Most gateways support per-user caching, where cache keys include user identifiers to prevent data leakage. Some platforms offer more sophisticated caching based on user roles or permissions, allowing shared caches for users with identical access rights.

"Edge caching transforms your API's global performance, but requires careful configuration to balance cache hit rates with data freshness across distributed locations."

Cache Invalidation Strategies

The most challenging aspect of caching involves ensuring users receive fresh data when the underlying source changes. Poor cache invalidation leads to users seeing stale data, potentially causing confusion, errors, or security issues. Effective invalidation strategies balance data freshness with caching benefits, removing or updating cached data precisely when necessary.

Time-Based Expiration

The simplest invalidation approach uses time-based expiration where cached items automatically expire after a predetermined duration. Setting appropriate TTL values requires understanding your data's change frequency and staleness tolerance. User profiles might cache for minutes or hours, while product inventory data might need sub-minute TTLs.

⚡ Short TTLs (seconds to minutes) work for rapidly changing data like stock prices, inventory levels, or real-time dashboards. This approach minimizes staleness but reduces cache effectiveness.

⏰ Medium TTLs (minutes to hours) suit content that changes periodically but where some staleness is acceptable, such as news articles, social media feeds, or product catalogs.

📅 Long TTLs (hours to days) apply to relatively static content like user profiles, historical data, or reference information that rarely changes.

🔄 Very long TTLs with manual invalidation work for content that changes infrequently and predictably, such as configuration data or localization strings.

🎯 Infinite TTLs with versioned URLs suit truly immutable content where changes result in new URLs, such as hashed static assets or versioned API endpoints.

Implement gradual TTL strategies where different cache layers use different expiration times. Browser caches might use shorter TTLs than server-side caches, providing a balance between freshness and performance. This layered approach ensures that even if edge caches serve slightly stale data, it refreshes reasonably quickly.

Event-Based Invalidation

More sophisticated systems use event-based invalidation where cache entries are removed or updated immediately when underlying data changes. This approach provides the best balance between cache effectiveness and data freshness, as cached data remains fresh indefinitely until explicitly invalidated.

Implement event-based invalidation by triggering cache removal in the same transaction that updates source data. When a user updates their profile, the code that saves changes to the database should also delete the cached profile data. This ensures subsequent requests fetch fresh data while maintaining cache hits for unchanged data.

For distributed systems, use message queues or pub/sub systems to broadcast invalidation events across multiple application instances and cache layers. When one server updates data, it publishes an invalidation message that other servers consume, removing their cached copies. Redis pub/sub, RabbitMQ, or cloud-native messaging services facilitate this pattern.

Tag-based invalidation provides a powerful mechanism for invalidating related cached items. Assign tags to cached entries representing relationships or categories: a product might have tags for its category, brand, and related products. When any related data changes, invalidate all entries with the relevant tag. This approach simplifies complex invalidation scenarios where a single change affects multiple cached items.

Partial Invalidation and Cache Warming

Rather than completely removing cached data, consider partial invalidation strategies that update specific fields or refresh data in the background. This approach maintains cache hit rates while ensuring freshness, particularly for large or complex cached objects where only portions change frequently.

Implement background refresh patterns where cache entries are refreshed asynchronously before expiration. When a cache entry approaches its TTL, trigger a background job to fetch fresh data and update the cache. This ensures users always receive cached responses while data remains fresh. This pattern works exceptionally well for popular content that would cause thundering herd problems if many requests simultaneously encountered a cache miss.

"Effective cache invalidation isn't about removing data quickly—it's about maintaining the optimal balance between serving fresh content and maximizing cache hit rates."

Advanced Caching Patterns

Beyond basic caching strategies, several advanced patterns address specific challenges in distributed systems, high-traffic applications, and complex data relationships. These approaches require more sophisticated implementation but provide significant benefits in appropriate scenarios.

Cache-Aside Pattern

The cache-aside (or lazy loading) pattern represents the most common caching approach where the application code explicitly manages cache interactions. When handling a request, the application first checks the cache. On a cache hit, it returns the cached data immediately. On a cache miss, it fetches data from the source, stores it in cache, then returns it to the caller.

This pattern provides maximum control over caching behavior and works well with existing applications since it requires no changes to data sources. However, it places the burden of cache management on application developers, who must remember to cache data consistently and invalidate it appropriately. Missing cache calls in code paths can lead to stale data or reduced cache effectiveness.

Read-Through and Write-Through Caching

Read-through caching abstracts cache management into a caching layer that sits between the application and data source. The application requests data from the cache layer, which automatically fetches from the source on cache misses and stores the result before returning it. This pattern simplifies application code by eliminating explicit cache management logic.

Write-through caching extends this concept to write operations. When the application updates data, it writes to the cache layer, which synchronously updates both the cache and the underlying data source. This approach ensures cache consistency but introduces latency since writes must complete in both systems before returning success.

Write-behind (or write-back) caching improves write performance by updating the cache immediately and asynchronously persisting changes to the data source. This approach provides excellent write performance but introduces complexity around failure handling—if the cache server fails before persisting changes, data can be lost. Use write-behind caching only when you can tolerate potential data loss or implement sophisticated failure recovery mechanisms.

Refresh-Ahead Caching

Refresh-ahead caching proactively refreshes cached data before it expires, ensuring popular items remain cached with fresh data. This pattern monitors cache access patterns and automatically refreshes frequently accessed entries before they expire. This approach eliminates cache misses for popular content while allowing less popular items to expire naturally.

Implement refresh-ahead caching by tracking access frequency and last access time for cached items. When an item is accessed and its age exceeds a threshold (perhaps 80% of its TTL), trigger an asynchronous refresh. This ensures the next request finds fresh data in cache without waiting for a fetch operation.

This pattern works exceptionally well for content with predictable access patterns, such as homepage data, popular product listings, or trending content. However, it can waste resources refreshing data that users stop accessing, so implement access frequency thresholds to avoid refreshing rarely used items.

| Pattern | Best For | Complexity | Data Consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cache-Aside | General purpose caching with full control | Low - application manages cache explicitly | Eventual consistency - depends on TTL and invalidation |

| Read-Through | Simplifying application code with automatic cache management | Medium - requires cache layer infrastructure | Eventual consistency - automatic cache population |

| Write-Through | Scenarios requiring strong consistency between cache and source | Medium - synchronous writes to both layers | Strong consistency - cache and source updated together |

| Write-Behind | High write throughput with acceptable data loss risk | High - requires failure recovery mechanisms | Eventual consistency - async persistence introduces risk |

| Refresh-Ahead | Popular content with predictable access patterns | High - requires access tracking and proactive refresh | Strong freshness - proactive updates before expiration |

Monitoring and Optimizing Cache Performance

Implementing caching strategies represents just the beginning—ongoing monitoring and optimization ensure your caching approach delivers expected benefits while avoiding common pitfalls. Effective monitoring provides visibility into cache effectiveness, identifies opportunities for improvement, and alerts you to problems before they impact users.

Key Metrics to Track

The cache hit ratio represents the most critical metric, measuring the percentage of requests served from cache. Calculate this by dividing cache hits by total requests (hits plus misses). A healthy cache hit ratio varies by application but typically ranges from 80% to 95% for well-cached content. Lower ratios suggest opportunities for caching more data or extending TTLs; higher ratios might indicate overly aggressive caching that serves stale data.

Monitor cache latency to ensure your caching layer performs as expected. Cache hits should be dramatically faster than origin requests—if they're not, investigate network issues, cache system performance, or serialization overhead. Track both average and percentile latencies (p50, p95, p99) to identify outliers and ensure consistent performance.

Eviction rate measures how frequently cached items are removed before expiration, typically due to memory pressure. High eviction rates indicate insufficient cache capacity or poor cache key distribution. This metric helps you right-size your cache infrastructure and identify hot keys that consume disproportionate resources.

Track cache memory usage to prevent out-of-memory conditions and optimize resource allocation. Monitor both current usage and growth trends to anticipate when you'll need additional capacity. Most caching systems provide built-in metrics for memory consumption, item counts, and memory fragmentation.

"What gets measured gets managed. Comprehensive cache metrics transform caching from a black box into a well-understood, continuously optimized system component."

Identifying and Resolving Cache Problems

The thundering herd problem occurs when many requests simultaneously encounter a cache miss for the same item, causing a spike of requests to your backend. This often happens when popular cached items expire, and multiple concurrent requests try to regenerate the cache entry. Implement request coalescing where the first request fetches fresh data while subsequent requests wait for the result, or use probabilistic early expiration where items refresh slightly before their TTL expires.

Cache penetration happens when requests for non-existent data bypass the cache and hit your database repeatedly. Malicious actors might exploit this to overload your system by requesting random keys. Mitigate this by caching negative results (storing a special value indicating the item doesn't exist) with short TTLs, or implementing bloom filters that quickly identify keys that definitely don't exist.

Cache stampede resembles the thundering herd but occurs when many different cache entries expire simultaneously, causing a sudden surge of database requests. Avoid this by adding random jitter to TTLs so expirations spread over time rather than clustering. Instead of setting all items to expire in exactly 300 seconds, use 300 ± random(0, 30) seconds.

Hot key problems arise when a single cache key receives disproportionate traffic, potentially overwhelming a single cache server in distributed systems. Identify hot keys through access frequency monitoring and address them through replication (copying the hot key to multiple cache servers) or local caching (maintaining hot keys in application memory).

Optimizing Cache Effectiveness

Regularly analyze which endpoints benefit most from caching and which don't. Use application performance monitoring to identify slow endpoints and determine if caching would help. Not all slow endpoints benefit from caching—some are slow due to complex computations rather than data fetching, and caching won't help unless you cache the computation results.

Experiment with different TTL values based on actual data change frequencies. Start with conservative (short) TTLs and gradually increase them while monitoring staleness complaints and cache hit ratios. Some teams implement dynamic TTLs that adjust based on data volatility—frequently changing data gets shorter TTLs, while stable data gets longer ones.

Optimize cache key design to maximize hit rates while maintaining correctness. Overly specific keys (including unnecessary parameters) reduce hit rates, while overly broad keys risk serving incorrect data to some users. Review cache keys periodically to ensure they include all relevant parameters but nothing extraneous.

Consider implementing cache warming strategies where you proactively populate caches during low-traffic periods or after deployments. This prevents the cold start problem where the first requests after cache clearing experience slow response times. Automated cache warming scripts can request key URLs to populate caches before real traffic arrives.

Security Considerations in API Caching

Caching introduces security considerations that developers must address to prevent data leaks, unauthorized access, and other vulnerabilities. Improperly configured caching can expose sensitive information to unauthorized users or allow attackers to poison caches with malicious content.

Preventing Cache-Based Data Leaks

The most critical security concern involves ensuring users never receive cached data they shouldn't access. This typically happens when cache keys don't include user identifiers or permission levels, causing responses cached for one user to be served to others. Always include user identifiers or session tokens in cache keys for personalized or access-controlled content.

Be particularly careful with HTTP caching headers on responses containing sensitive information. The Cache-Control: private directive prevents shared caches (CDNs, proxies) from storing responses, ensuring they're only cached in user browsers. For highly sensitive data, use Cache-Control: no-store to prevent any caching whatsoever.

Review all cached endpoints to identify which contain sensitive information. User profiles, financial data, personal messages, and access-controlled resources should either not be cached or use user-specific cache keys. Consider implementing automated tests that verify sensitive endpoints include appropriate cache headers and don't leak data across user boundaries.

Cache Poisoning Prevention

Cache poisoning attacks involve tricking a cache into storing malicious content that's then served to other users. This typically exploits endpoints that reflect user input in responses without proper sanitization. An attacker might craft a request with malicious content that gets cached and served to legitimate users.

Prevent cache poisoning by carefully controlling which request components influence cache keys. Don't include arbitrary headers in cache keys unless necessary, and validate all input that affects cached responses. Implement strict input validation and output encoding to prevent injection attacks even if responses are cached.

Consider implementing cache key normalization where you standardize request parameters before generating cache keys. This prevents attackers from bypassing caches or creating excessive cache entries through parameter manipulation. For example, normalize query parameter order and case to prevent ?a=1&b=2 and ?b=2&a=1 from creating separate cache entries.

"Security in caching isn't optional—it's fundamental. A single misconfigured cache can expose sensitive data to thousands of users or enable sophisticated attacks."

Authentication and Authorization with Caching

Caching authenticated API endpoints requires careful consideration of how authentication tokens and session information interact with cache keys. The simplest approach includes the user identifier in the cache key, ensuring each user has separate cache entries. However, this reduces cache efficiency since identical data is cached multiple times for different users.

For data that's identical across users but requires authentication to access, consider implementing permission-based caching. Cache the data once but verify permissions before serving cached responses. This approach maximizes cache efficiency while maintaining security, though it requires careful implementation to avoid race conditions or time-of-check-time-of-use vulnerabilities.

Some applications implement role-based caching where users with identical permissions share cache entries. For example, all "premium" users might share cached responses while "free" users see different cached content. This approach balances cache efficiency with personalization, though it requires careful management of role changes and permission updates.

Caching in Microservices Architectures

Microservices introduce unique caching challenges and opportunities. With multiple services contributing to API responses, cache strategies must address service boundaries, data consistency across services, and the complexity of distributed caching in a service mesh environment.

Service-Level Caching

Each microservice can implement its own caching strategy optimized for its specific data and access patterns. User services might cache profile data aggressively, while inventory services use shorter TTLs due to frequent updates. This approach allows teams to independently optimize caching for their services without coordinating with other teams.

However, service-level caching can lead to inconsistencies when multiple services cache related data. If the user service caches profile data and the order service caches user names, updates to user profiles might not propagate to the order service's cache. Address this through event-driven invalidation where services publish events when data changes, allowing other services to invalidate their caches accordingly.

API Gateway Caching for Aggregated Responses

When API gateways aggregate responses from multiple microservices, caching at the gateway level can dramatically reduce the number of internal service calls. The gateway can cache entire aggregated responses, eliminating calls to multiple backend services for frequently requested data.

Implement intelligent cache invalidation at the gateway by subscribing to change events from backend services. When any service publishes a change event for data included in cached responses, the gateway can invalidate affected cache entries. This approach maintains cache consistency while maximizing cache effectiveness across service boundaries.

Distributed Caching Strategies

Microservices often share a distributed cache like Redis Cluster to maintain consistency across service instances. This approach allows multiple services to access the same cached data, reducing duplication and ensuring consistency. However, it creates a shared dependency that all services must maintain and coordinate around.

Implement cache namespacing to prevent key collisions between services. Use prefixes like user-service:profile:123 and order-service:user:123 to clearly identify which service owns each cache entry. This makes debugging easier and allows services to manage their cache entries independently without affecting others.

Consider implementing cache tiering where services maintain local in-memory caches for frequently accessed data while using distributed caches for less frequent data. This hybrid approach provides the speed of local caching with the consistency of distributed caching, though it introduces complexity around keeping local caches synchronized with the distributed cache.

Practical Implementation Examples

Understanding caching concepts is valuable, but seeing practical implementations helps solidify these ideas. The following examples demonstrate common caching patterns in different technology stacks, providing starting points for your own implementations.

Implementing Cache-Aside with Redis in Node.js

A typical cache-aside implementation in Node.js with Redis might look like this: First, check if data exists in Redis. If found, return it immediately. If not, fetch from the database, store in Redis with an appropriate TTL, then return the data. This pattern requires explicit cache management in your code but provides maximum control.

The implementation wraps database queries in cache logic. Before querying the database, generate a cache key based on the query parameters. Use this key to check Redis for cached results. On a cache miss, execute the query, serialize the results, and store them in Redis with a TTL that balances freshness and cache effectiveness. For user profiles that change infrequently, a TTL of 5-15 minutes often works well.

Handle cache failures gracefully by catching Redis errors and falling back to database queries. Your application should continue functioning even if the cache becomes unavailable. Log cache errors for monitoring but don't let cache issues break your API. This resilience pattern ensures caching improves performance without introducing new failure modes.

HTTP Caching Headers in REST APIs

Properly configured HTTP headers transform client-side caching effectiveness. For a product catalog endpoint that updates hourly, set headers like Cache-Control: public, max-age=3600 and include an ETag based on the catalog's last modification time. This allows browsers and CDNs to cache responses for an hour while providing a validation mechanism for conditional requests.

For user-specific endpoints like profile APIs, use Cache-Control: private, max-age=300 to cache in browsers only, preventing shared caches from storing personalized data. Include a Vary: Authorization header to ensure caches treat requests with different authentication tokens as separate cache entries.

Implement conditional request handling by checking If-None-Match headers against current ETags. If they match, return a 304 Not Modified response with no body, saving bandwidth while confirming cached data remains valid. This pattern works exceptionally well for mobile applications where bandwidth is limited and users frequently request the same data.

Distributed Caching with Consistent Hashing

When implementing distributed caching across multiple cache servers, consistent hashing ensures keys are distributed evenly while minimizing cache misses when servers are added or removed. This algorithm maps both cache keys and server nodes to points on a circular hash space, assigning each key to the nearest server in the circle.

Many Redis client libraries implement consistent hashing automatically. When configured with multiple Redis servers, they distribute keys across servers using consistent hashing, providing automatic failover and load distribution. This approach scales horizontally by adding more cache servers without requiring complete cache invalidation.

Implement cache replication for high-availability scenarios where cache misses are expensive. Redis Sentinel or Redis Cluster provide automatic replication and failover, ensuring cached data remains available even if individual servers fail. This adds operational complexity but provides crucial reliability for applications where cache availability significantly impacts user experience.

Frequently Asked Questions

What's the difference between caching and memoization?

Caching stores data from external sources (databases, APIs) to avoid repeated fetches, while memoization caches the results of function calls to avoid repeated computations. Memoization is a specific type of caching applied to function outputs. Both improve performance by avoiding redundant work, but they operate at different levels—caching typically involves I/O operations, while memoization focuses on computational results.

How do I determine the right TTL for cached data?

Start by understanding how frequently your data changes and how much staleness your users can tolerate. Monitor actual change frequencies in your data sources and set TTLs slightly shorter than typical change intervals. For example, if data typically updates every 10 minutes, a TTL of 5-8 minutes balances freshness with cache effectiveness. Adjust based on cache hit ratios and user feedback about stale data. Different data types require different TTLs—user preferences might cache for hours, while inventory levels need minute-level TTLs.

Should I cache error responses?

It depends on the error type. Don't cache 5xx server errors, as they indicate temporary problems that shouldn't be propagated to future requests. Consider caching 4xx client errors like 404 Not Found with short TTLs to prevent repeated requests for non-existent resources, which can help mitigate certain types of attacks. However, be cautious with errors that might be temporary (like 429 Rate Limit Exceeded) or user-specific (like 401 Unauthorized), as caching these could create confusing user experiences.

How can I test my caching implementation?

Implement comprehensive testing at multiple levels. Unit tests should verify cache key generation, TTL settings, and invalidation logic. Integration tests should confirm cached data is served correctly and invalidates appropriately when source data changes. Load tests help identify cache effectiveness under realistic traffic patterns and reveal issues like thundering herds or hot keys. Monitor cache hit ratios, latency, and error rates in production to ensure your caching strategy delivers expected benefits. Consider implementing cache bypass mechanisms for testing that allow verifying fresh data without cache interference.

What happens when my cache becomes full?

Most caching systems implement eviction policies that automatically remove entries when memory fills up. Common policies include LRU (Least Recently Used), which removes the least recently accessed items, LFU (Least Frequently Used), which removes the least frequently accessed items, and TTL-based eviction, which removes expired items first. Choose an eviction policy that matches your access patterns. For cache systems that don't auto-evict, you'll need to implement manual memory management, monitoring cache size and proactively removing old or less important entries before memory exhaustion occurs. Proper capacity planning helps avoid frequent evictions that reduce cache effectiveness.

Can caching help with rate limiting?

Yes, effective caching reduces the number of requests reaching rate-limited APIs, helping you stay within limits. By serving repeated requests from cache, you avoid making redundant API calls that consume your rate limit quota. This is particularly valuable when working with third-party APIs that have strict rate limits. However, ensure your cache invalidation strategy accounts for rate-limited APIs—if you cache data for too long, you might serve stale information. Consider implementing request coalescing where multiple simultaneous requests for the same data result in a single API call, with all requesters receiving the result.