How to Implement Clean Architecture Principles

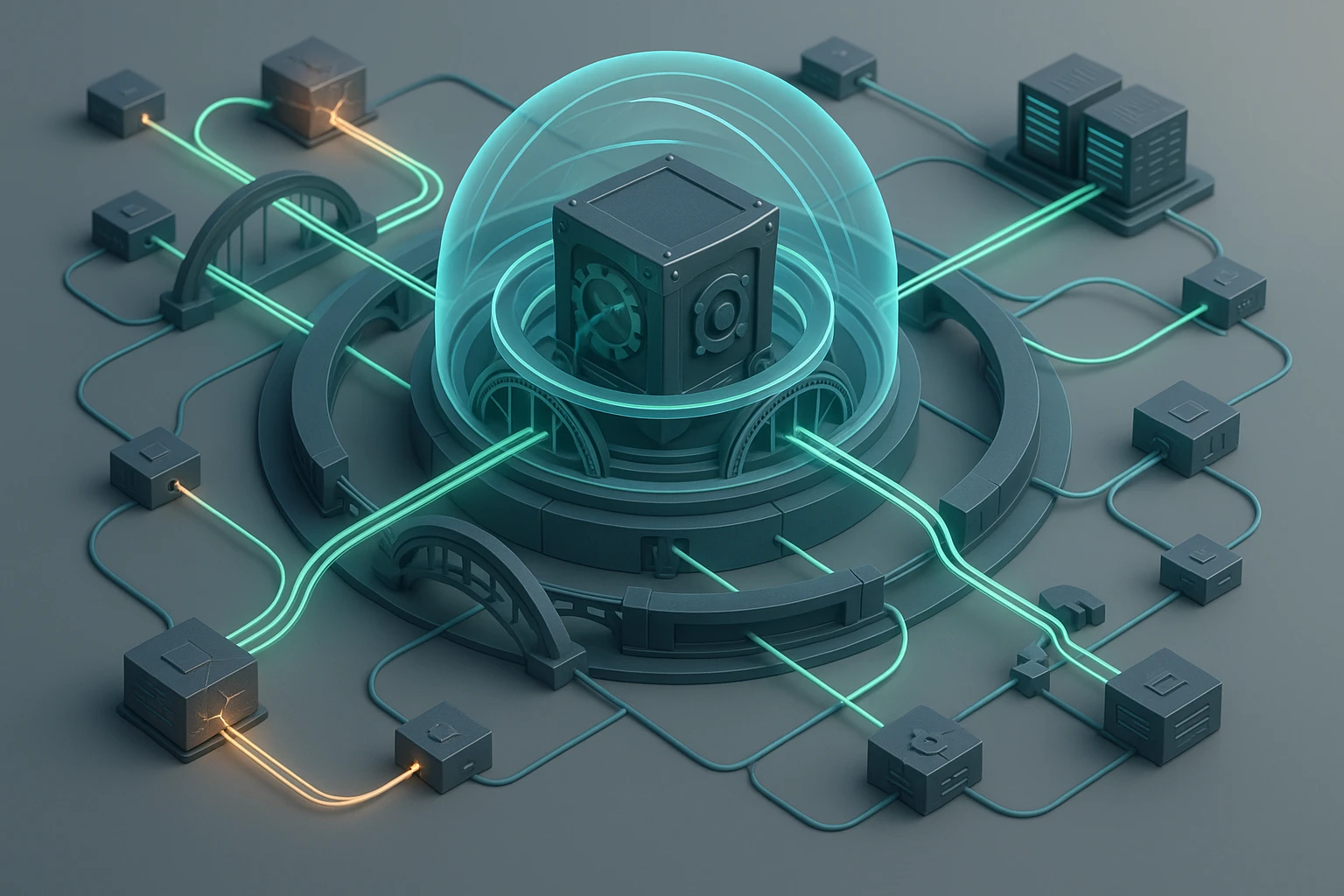

Visual Clean Architecture diagram: layered circles (entities, use cases, interfaces, frameworks) showing dependency rule, separation, testable boundaries, inversion of control viz.

How to Implement Clean Architecture Principles

Software systems that stand the test of time share a common trait: they're built on solid architectural foundations that separate concerns, promote maintainability, and adapt gracefully to change. As applications grow in complexity and teams expand, the architecture becomes the invisible framework that either enables rapid development or creates bottlenecks that slow everything down. The principles we choose at the beginning of a project ripple through every line of code, every deployment, and every feature request that follows.

Clean Architecture represents a systematic approach to organizing code that prioritizes independence from frameworks, databases, and external agencies. Rather than building applications around tools and technologies, this methodology centers on business logic and use cases, treating infrastructure as replaceable details. This perspective offers multiple benefits: testability without external dependencies, flexibility to swap implementations, and clarity that helps teams understand and modify systems years after initial development.

Throughout this exploration, you'll discover practical strategies for structuring applications according to these principles, understand the layers that compose a clean system, and learn how to navigate the challenges that emerge during implementation. We'll examine concrete patterns for dependency management, explore testing approaches that leverage architectural boundaries, and provide actionable guidance for teams transitioning from traditional structures to cleaner alternatives.

Understanding the Core Layers

The foundation of this architectural approach rests on a series of concentric circles, each representing a different layer of the application. The innermost circles contain business logic and domain models—the essence of what the application does—while outer circles handle infrastructure concerns like databases, web frameworks, and external services. This arrangement creates a dependency rule: source code dependencies must point inward, meaning inner layers know nothing about outer layers.

At the center sits the Enterprise Business Rules layer, containing entities that encapsulate the most general and high-level rules. These objects represent the core business concepts and would exist regardless of whether the application is a web service, desktop application, or command-line tool. They change only when fundamental business requirements change, making them the most stable part of the system.

Surrounding the entities, the Application Business Rules layer contains use cases that orchestrate the flow of data to and from entities. Each use case represents a specific operation the system can perform, such as creating an order, updating a user profile, or generating a report. Use cases coordinate entities and direct them to use their business rules to achieve the goals of the application, but they remain independent of how data is presented or persisted.

"The architecture should scream the intent of the system, not the frameworks it uses. When you look at the top-level directory structure, you should immediately understand what the application does, not what tools it employs."

The Interface Adapters layer converts data from the format most convenient for use cases and entities to the format most convenient for external agencies like databases and web frameworks. Controllers, presenters, and gateways live here, translating between the pure business logic and the messy real world of HTTP requests, database rows, and API responses.

Finally, the outermost Frameworks and Drivers layer contains frameworks, tools, and implementation details. Databases, web frameworks, device drivers, and external libraries exist at this level. This layer changes frequently as technologies evolve, but because dependencies point inward, these changes don't ripple through the entire system.

| Layer | Responsibilities | Change Frequency | Dependencies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entities | Core business rules, domain models, enterprise-wide logic | Very Low | None |

| Use Cases | Application-specific business rules, orchestration logic | Low | Entities only |

| Interface Adapters | Controllers, presenters, gateways, data conversion | Medium | Use Cases, Entities |

| Frameworks & Drivers | External tools, databases, web frameworks, devices | High | Interface Adapters |

Establishing Dependency Inversion

The secret to maintaining the dependency rule lies in dependency inversion, a principle that allows source code dependencies to oppose the flow of control. While control flows from controllers through use cases to entities and back out through presenters, the source code dependencies point inward at every step. This inversion happens through abstractions—interfaces and abstract classes that define contracts without specifying implementations.

Consider a use case that needs to persist data. Rather than depending directly on a database implementation, the use case defines an interface that describes what it needs: methods for saving, retrieving, and querying data. The actual database implementation lives in the outer layer and implements this interface. The use case depends only on the abstraction, while the database implementation depends on both the abstraction and the concrete database technology.

This pattern repeats throughout the architecture. Controllers depend on use case interfaces, not concrete implementations. Use cases depend on repository interfaces, not specific databases. Presenters depend on view model interfaces, not particular UI frameworks. Each boundary between layers represents an opportunity to inject dependencies, swap implementations, and test components in isolation.

"Dependencies should flow toward stability. The most stable parts of the system—those that change least frequently—should be at the center, while volatile details remain at the edges where they can be easily modified or replaced."

Practical Dependency Management

Implementing dependency inversion requires deliberate choices about how objects are created and connected. Rather than allowing high-level components to instantiate their own dependencies, responsibility for object creation moves to composition roots—specific locations where the application assembles its components. These might be main functions, dependency injection containers, or factory classes that understand the concrete implementations available.

The key patterns that enable this structure include:

- 🔧 Constructor Injection: Dependencies are passed to objects when they're created, making requirements explicit and enabling easy substitution during testing

- 📋 Interface Segregation: Small, focused interfaces ensure that components depend only on the methods they actually use, reducing coupling and improving flexibility

- 🎯 Dependency Injection Containers: Frameworks that automate the process of creating objects and resolving their dependencies based on configured mappings

- 🏭 Factory Patterns: Objects that encapsulate the logic for creating other objects, hiding concrete implementations behind abstractions

- 🔌 Plugin Architecture: Systems designed so that new implementations can be added without modifying existing code, simply by implementing defined interfaces

Structuring Use Cases

Use cases represent the heart of the application—the specific operations users can perform and the business value the system provides. Each use case should be a single class or module that encapsulates one complete operation, from receiving input to producing output. This granular approach creates code that's easy to understand, test, and modify without affecting unrelated functionality.

A well-designed use case follows a consistent structure. It receives input through a request object that contains all necessary data, validates that input according to business rules, coordinates with entities and repositories to perform the operation, and produces output through a response object or by calling methods on a presenter. This structure keeps use cases focused and prevents them from becoming tangled with presentation or persistence concerns.

Input and Output Boundaries

The boundaries between use cases and the outside world deserve special attention. Rather than accepting primitive types or framework-specific objects, use cases should define their own request and response structures. These data transfer objects serve as contracts that specify exactly what information the use case needs and what it will provide, independent of how that data arrives or where it goes.

Request objects gather all input parameters into a single structure, making it clear what information is required and optional. They might include validation logic to ensure data meets basic requirements before the use case executes. Response objects similarly package output data, but in many cases, use cases communicate results through presenter interfaces that allow different output formats without changing the use case itself.

"Use cases should read like well-written specifications. When you examine a use case, you should understand exactly what business operation it performs without needing to trace through layers of infrastructure code or framework abstractions."

Managing Data Flow

Data crosses multiple boundaries as it flows through a clean architecture, and each crossing requires transformation. Data arrives from external sources in formats convenient for those sources—HTTP request bodies, database rows, message queue payloads. It must be converted into the domain models and value objects that entities understand, then transformed again into the formats expected by use cases, and finally converted once more for presentation or persistence.

These transformations happen at the boundaries between layers, performed by adapters that understand both sides of the boundary. Controllers adapt from web framework request objects to use case request objects. Repositories adapt from domain entities to database models and back. Presenters adapt from use case responses to view models suitable for display. Each adapter isolates a layer from the details of adjacent layers.

| Boundary | Data Transformation | Responsible Component |

|---|---|---|

| External → Use Case | HTTP/API request → Request DTO | Controller |

| Use Case → Entity | Request DTO → Domain Model | Use Case Interactor |

| Entity → Persistence | Domain Model → Database Schema | Repository Implementation |

| Use Case → Presentation | Response DTO → View Model | Presenter |

| Presentation → External | View Model → HTTP/API response | View/Serializer |

Avoiding Data Structure Coupling

One of the most subtle forms of coupling occurs when multiple layers share the same data structures. It seems efficient to pass database entities directly to the presentation layer or to use API request objects throughout the application, but this creates hidden dependencies that make change difficult. When the database schema changes, presentation code breaks. When API contracts evolve, business logic must be updated.

The solution involves creating separate data structures for each layer, even when they appear similar. Domain entities represent business concepts and contain business logic. Database models represent persistence structures and include annotations or configurations for the ORM. Request and response DTOs represent API contracts and include serialization metadata. View models represent presentation needs and contain formatting logic. Though this creates more classes, it provides the flexibility to evolve each layer independently.

Implementing Repository Patterns

Repositories provide the abstraction between use cases and data persistence, allowing business logic to work with domain objects without knowing how or where they're stored. A repository interface defines methods for storing and retrieving entities using domain language—saving orders, finding users by email, listing active subscriptions—while implementations handle the technical details of database queries, caching, and data mapping.

The repository interface belongs to the domain or use case layer, expressing what the business logic needs in terms it understands. Multiple implementations might exist: one for production using a SQL database, another for testing using in-memory collections, and perhaps a third for integration environments using a different database technology. Use cases depend only on the interface, remaining unaware of which implementation is active.

"Repositories should speak the language of the domain, not the language of the database. Methods like 'findActiveCustomersInRegion' are preferable to 'executeQuery' because they express business intent rather than technical operations."

Query and Command Separation

Repositories often benefit from separating query operations from command operations. Queries retrieve data without modifying state, while commands change state without returning data. This separation, known as CQRS in its more elaborate forms, allows different optimization strategies for reads and writes and makes the intent of each operation clear.

Query methods might return read-only projections optimized for specific use cases, potentially bypassing entity construction entirely when only a subset of data is needed. Command methods work with full entities, ensuring business rules are enforced during modifications. This distinction becomes particularly valuable as systems scale and read patterns diverge from write patterns.

Testing Across Boundaries

The architectural boundaries that separate concerns also create natural testing boundaries. Each layer can be tested in isolation by substituting test doubles for its dependencies, allowing fast, focused tests that verify specific behaviors without involving the entire system. This testing strategy produces suites that run quickly, fail clearly, and remain maintainable as the system grows.

Entity tests verify business rules without touching databases or frameworks. Use case tests confirm orchestration logic using mock repositories and presenters. Controller tests ensure proper request handling and response formatting without executing real use cases. Repository tests validate data access logic against actual databases. Each test type serves a specific purpose and runs at an appropriate speed.

Test Double Strategies

Different testing scenarios call for different types of test doubles. Mocks verify that specific methods are called with expected arguments, useful for confirming that use cases interact correctly with repositories. Stubs return predetermined responses, allowing tests to simulate various scenarios without complex setup. Fakes provide working implementations with shortcuts, like in-memory repositories that behave like real databases but without persistence.

The choice of test double depends on what aspect of the system is under test. When verifying that a use case calls the correct repository method, a mock is appropriate. When testing how a use case handles different data scenarios, stubs that return various responses work well. When integration testing requires realistic behavior without external dependencies, fakes provide the right balance.

"The ability to test business logic without starting a web server, connecting to a database, or configuring external services is not a luxury—it's a fundamental requirement for maintaining velocity as systems grow."

Handling Cross-Cutting Concerns

Certain concerns cut across all layers of an application: logging, authentication, authorization, error handling, transaction management, and caching. These aspects need to be addressed without violating the dependency rule or polluting business logic with infrastructure details. Several patterns help manage these challenges while maintaining clean boundaries.

Decorator patterns allow cross-cutting concerns to be wrapped around use cases or repositories. A logging decorator might wrap a use case, recording entry and exit while delegating actual work to the wrapped implementation. A transaction decorator might begin a transaction before invoking a use case and commit or rollback afterward. Multiple decorators can be composed to layer concerns without modifying core logic.

Middleware and Pipeline Patterns

For web applications, middleware provides a mechanism to handle cross-cutting concerns at the framework level before requests reach controllers. Authentication, authorization, request logging, and error handling can be implemented as middleware components that process requests and responses without coupling to specific use cases. This approach keeps controllers thin and focused on adapting between the web framework and use cases.

Similarly, pipeline patterns allow use cases to be wrapped in processing stages that handle common concerns. A use case pipeline might include stages for validation, authorization, logging, and error handling, with each stage having the opportunity to short-circuit execution or modify input and output. This structure makes it easy to add or remove concerns without modifying individual use cases.

- 🔐 Authentication: Verify user identity in middleware before requests reach use cases, passing authenticated user context through request objects

- 🛡️ Authorization: Check permissions in decorators that wrap use cases, using domain-level rules rather than framework-specific mechanisms

- 📝 Logging: Implement as decorators around use cases and repositories, capturing domain events rather than technical details

- ⚠️ Error Handling: Define domain-specific exceptions in inner layers, translate to HTTP status codes or user messages in outer layers

- 💾 Caching: Add as decorators around repositories or use cases, transparent to business logic

Organizing Project Structure

The physical organization of code should reflect the architectural layers and make the system's intent immediately apparent. Rather than organizing by technical role—controllers in one directory, models in another, views in a third—organize by feature and layer. Someone examining the project structure should understand what the system does before understanding how it's built.

A typical structure might include top-level directories for each major feature or bounded context, with subdirectories representing architectural layers. Within a "customer" feature, you might find directories for entities, use cases, interfaces, and infrastructure. This organization makes it easy to locate all code related to a specific feature and clearly shows dependencies between layers.

Module and Package Design

Beyond directory structure, the module or package system enforces architectural boundaries at compile time. Inner layers should be packaged independently of outer layers, with explicit dependencies declared in build configurations. A use case module might depend on an entity module but should have no dependencies on controller or repository modules. Build tools can verify these constraints, preventing accidental violations.

Package visibility rules further enforce boundaries. Entities might expose public interfaces for use cases to consume while keeping implementation details private. Use cases might expose interfaces for controllers to invoke while hiding orchestration logic. This intentional design of public APIs at each layer creates clear contracts and prevents tight coupling.

Transitioning Existing Systems

Moving an existing application toward cleaner architecture rarely happens all at once. The pragmatic approach involves identifying boundaries in the current system, introducing abstractions at those boundaries, and gradually migrating functionality behind those abstractions. This incremental strategy allows teams to realize benefits early while minimizing risk and disruption.

Start by identifying the core business logic buried within controllers, services, or other components. Extract this logic into use case classes that express business operations clearly. Create interfaces for data access and implement them with adapters that wrap existing database code. As use cases accumulate, patterns emerge that guide further refactoring and reveal opportunities for consolidation.

"Perfection is not the goal. Every step toward cleaner boundaries, more explicit dependencies, and better separation of concerns improves the system, even if the entire architecture isn't transformed overnight."

Strangler Fig Pattern

The strangler fig pattern provides a proven approach for architectural migration. Rather than rewriting the entire system, build new functionality using clean architecture while leaving existing code in place. Gradually route more requests through the new implementation, and as confidence grows, migrate additional features. Eventually, the old implementation can be removed, having been "strangled" by the new architecture that grew around it.

This pattern minimizes risk because the old system continues functioning while the new one develops. It provides real-world feedback on the new architecture before full commitment. Teams can adjust the approach based on lessons learned from early migrations, and stakeholders see continuous value delivery rather than waiting for a big-bang rewrite.

Common Pitfalls and Solutions

Even with good intentions, teams encounter recurring challenges when implementing clean architecture. Recognizing these pitfalls and having strategies to address them helps maintain momentum and prevents architectural erosion over time.

Over-abstraction creates unnecessary complexity. Not every class needs an interface, and not every operation requires a separate use case. Apply abstractions where they provide value: at boundaries between layers, where testing requires isolation, or where multiple implementations exist. Simple operations that are unlikely to change might not justify the overhead of full architectural treatment.

Anemic domain models push all logic into use cases, leaving entities as mere data containers. While use cases orchestrate operations, entities should contain the business rules that govern their own state. If entities only have getters and setters, consider whether business logic has been misplaced in use cases or services.

Leaky abstractions expose implementation details through interfaces. A repository interface that includes methods like "executeSQL" or "getDbConnection" has failed to abstract the database. Interfaces should express domain concepts and remain independent of the technologies that implement them.

Shared kernel problems arise when multiple bounded contexts depend on the same entities. This creates coupling that makes independent evolution difficult. Consider duplicating entity definitions across contexts or using anti-corruption layers to translate between different representations of similar concepts.

Performance Considerations

Architectural boundaries and abstractions introduce indirection that theoretically impacts performance. In practice, these costs are negligible compared to database queries, network calls, and business logic complexity. However, understanding where performance matters and how to optimize within clean architecture ensures that architectural decisions don't create bottlenecks.

The primary performance concern involves data transformation across boundaries. Converting between database models, domain entities, DTOs, and view models requires CPU cycles and memory allocation. For most applications, this overhead is insignificant, but high-throughput systems might need optimization strategies.

Optimization Strategies

When performance becomes critical, several approaches maintain clean boundaries while improving efficiency. Query projections allow repositories to return only needed data in formats suitable for specific use cases, bypassing full entity construction. Caching can be added as decorators around repositories or use cases, transparent to business logic. Batch operations can be defined in repository interfaces, allowing implementations to optimize multiple operations together.

Profiling identifies actual bottlenecks rather than assumed ones. Often, performance problems stem from inefficient queries, missing indexes, or algorithmic issues rather than architectural overhead. Address real problems with targeted solutions, and resist the temptation to compromise architecture for theoretical performance gains that may never materialize.

Framework Integration

Clean architecture treats frameworks as details, but applications still need to integrate with web frameworks, ORMs, and other tools. The key is keeping these integrations at the outer layer, preventing framework concepts from leaking inward. Controllers and configuration code understand the framework, but use cases and entities remain framework-agnostic.

Most modern frameworks support dependency injection, making it straightforward to wire up clean architecture components. Configure the container to map interfaces to implementations, and let the framework handle object creation. Controllers become thin adapters that extract data from framework request objects, invoke use cases, and format responses using framework response objects.

ORM Integration

Object-relational mappers present a particular challenge because they often want to control entity definitions. The solution involves separating domain entities from persistence models. Domain entities live in the core layer and contain business logic. Persistence models live in the infrastructure layer and include ORM annotations. Repository implementations translate between these representations.

This separation allows domain entities to evolve based on business needs while persistence models evolve based on database optimization requirements. The two concerns remain independent, connected only through repository implementations that know how to map between them.

Scaling and Microservices

Clean architecture principles apply whether building a monolith or a distributed system. The boundaries that separate use cases from infrastructure in a single application become service boundaries in a microservices architecture. Each service can be structured using clean architecture internally, with well-defined interfaces for inter-service communication.

The advantage of starting with clean architecture in a monolith is that extracting services becomes straightforward. Use cases already have clear boundaries and explicit dependencies. Moving a set of related use cases to a separate service involves wrapping them in a service interface and implementing that interface as a remote call in the original application. The business logic doesn't change; only the mechanism for invoking it evolves.

Distributed System Considerations

Distributed systems introduce challenges that clean architecture helps address. Service interfaces define contracts between systems, similar to how use case interfaces define contracts between layers. Anti-corruption layers translate between different service representations of domain concepts. Event-driven communication can be modeled as use cases that respond to domain events rather than direct invocations.

The key is maintaining the dependency rule even across service boundaries. Services should depend on abstractions of other services, not concrete implementations. This allows services to evolve independently, with changes to one service's implementation not forcing changes to its consumers as long as contracts remain stable.

Documentation and Communication

Clean architecture makes systems more understandable, but this benefit only materializes if teams communicate architectural decisions effectively. Documentation should focus on explaining the layers, their responsibilities, and the rules that govern dependencies. Diagrams showing the flow of control and data through the system help new team members orient themselves quickly.

Code organization and naming conventions serve as implicit documentation. When use cases are grouped by feature, named clearly, and structured consistently, developers can navigate the codebase intuitively. Interfaces that express domain concepts rather than technical operations communicate intent without requiring separate documentation.

Architectural Decision Records

Recording architectural decisions preserves the reasoning behind structural choices. When the team decides how to handle a particular cross-cutting concern, which layer should own certain logic, or how to integrate a specific framework, document that decision along with the context and alternatives considered. Future developers benefit from understanding not just what the architecture is, but why it took its current form.

These records don't need to be elaborate. A simple template capturing the decision, context, consequences, and alternatives provides enough information to prevent repeated debates and helps teams maintain consistency as the system evolves.

Measuring Success

The value of clean architecture manifests in several measurable ways. Test coverage increases because components can be tested in isolation. Build times improve because changes to outer layers don't require recompiling inner layers. Development velocity stabilizes over time rather than declining as the codebase grows. Onboarding time for new developers decreases because the system's structure makes it easier to understand.

More subjectively, teams report greater confidence making changes, less fear of breaking unrelated functionality, and clearer understanding of where new features should be implemented. Code reviews focus more on business logic correctness and less on untangling dependencies or tracing through layers of indirection.

Track metrics that matter to your team and organization. If deployment frequency is important, measure whether architectural changes enable more frequent releases. If bug rates are a concern, track whether they decrease as architectural boundaries solidify. If developer satisfaction matters, survey the team about their experience working with the codebase.

What is the main benefit of implementing clean architecture?

The primary benefit is independence—independence from frameworks, databases, UI, and external agencies. This independence makes the system more testable, maintainable, and flexible. Business logic can be tested without databases or web servers, frameworks can be swapped without rewriting business rules, and the system can adapt to changing requirements without extensive rewrites.

How do I know if my application needs clean architecture?

Applications that will be maintained long-term, have complex business logic, require high test coverage, or need flexibility to change implementations benefit most from clean architecture. If your application is a simple CRUD interface with minimal business rules, the overhead might not be justified. Consider factors like expected lifespan, team size, business complexity, and how frequently requirements change.

Can I implement clean architecture gradually in an existing project?

Yes, incremental adoption is often the most practical approach. Start by identifying and extracting core business logic into use cases. Create interfaces for data access and implement them with adapters around existing code. As new features are added, implement them using clean architecture principles. Over time, the proportion of clean code increases while risk remains manageable.

How many layers should my application have?

The four-layer model (entities, use cases, interface adapters, frameworks) provides a good starting point, but the exact number depends on your needs. Some applications benefit from additional layers that separate read and write operations or distinguish between different types of business rules. The key is maintaining the dependency rule: dependencies always point inward toward more stable abstractions.

Does clean architecture make development slower?

Initially, setting up the structure and creating interfaces requires more code than directly implementing features. However, this upfront investment pays dividends as the project matures. Changes become easier because they're isolated to specific layers, testing becomes faster because components can be verified in isolation, and new features can be added without understanding the entire system. Teams typically find that velocity increases over the project lifecycle.

How do I handle shared code between use cases?

Shared logic belongs in one of several places depending on its nature. Business rules that apply to entities belong in those entities. Operations that coordinate multiple entities might belong in domain services that use cases can invoke. Purely technical concerns like data validation or transformation might belong in shared utilities. Avoid creating a "common" layer that everything depends on, as this creates coupling and violates the dependency rule.