How to Implement Hexagonal Architecture

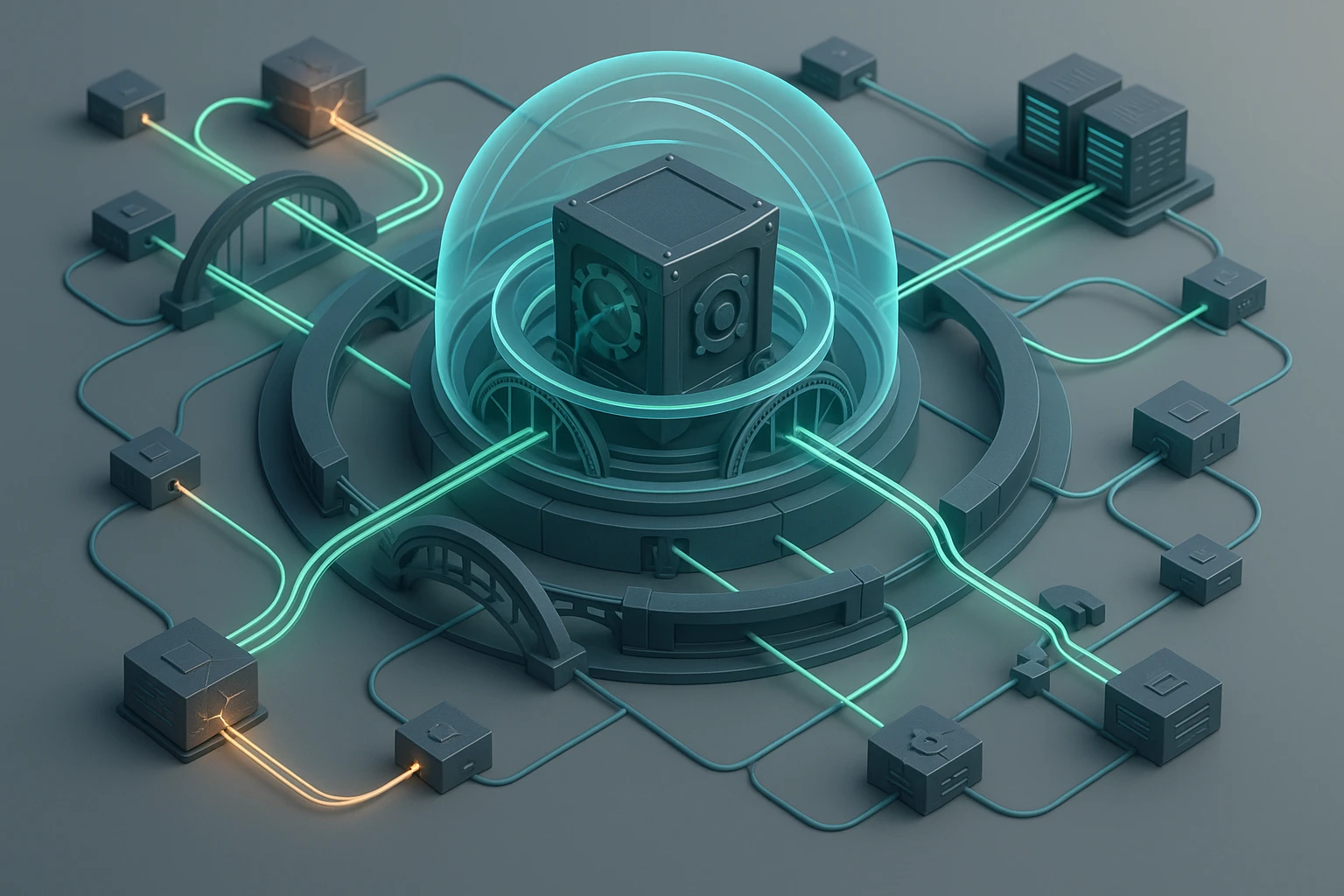

Diagram of Hexagonal Architecture: central domain core inside hexagon, ports/interfaces on edges, adapters and external systems around, arrows show dependency inversion, tests, UI.

In today's rapidly evolving software landscape, the way we structure our applications determines not just their immediate functionality, but their long-term viability, maintainability, and adaptability. Every developer has faced the nightmare of tightly coupled code where changing a database means rewriting half the application, or where testing requires spinning up entire infrastructure stacks. These pain points aren't just inconveniences—they represent real costs in time, money, and developer sanity that compound over the lifetime of a project.

Hexagonal Architecture, also known as Ports and Adapters pattern, offers a systematic approach to building software that remains flexible, testable, and independent of external concerns. Rather than treating this as just another architectural buzzword, we'll explore it as a practical philosophy that separates what your application does from how it does it, creating boundaries that protect your core business logic from the volatile world of frameworks, databases, and third-party services.

Throughout this comprehensive guide, you'll discover the fundamental principles that make Hexagonal Architecture work, learn how to identify and implement ports and adapters in your own projects, understand the relationship between domain logic and infrastructure concerns, and gain practical strategies for migrating existing codebases. Whether you're starting fresh or refactoring legacy systems, you'll find actionable insights that translate directly into cleaner, more maintainable code.

Understanding the Core Philosophy Behind Hexagonal Architecture

At its heart, this architectural approach addresses a fundamental problem in software development: dependencies flow in the wrong direction. Traditional layered architectures create situations where business logic becomes intimately aware of database schemas, HTTP frameworks, or message queue implementations. When these external concerns change—and they always do—the ripple effects cascade through your entire codebase.

The philosophy reverses this dependency flow by placing domain logic at the center, completely isolated from technical implementation details. Everything else becomes an adapter that translates between the domain's language and the outside world's requirements. This isn't just theoretical elegance; it's a practical solution that enables teams to defer infrastructure decisions, swap implementations without touching business logic, and test core functionality without external dependencies.

"The biggest revelation comes when you realize your business logic doesn't need to know whether data comes from PostgreSQL, MongoDB, or an in-memory cache. It simply expresses what it needs, and adapters fulfill those needs."

Think of your application as having a protected core surrounded by a defensive perimeter. The core contains everything that makes your application unique—your business rules, domain models, and use cases. The perimeter handles all the messy details of communicating with databases, web frameworks, file systems, and external APIs. This separation isn't arbitrary; it reflects the reality that business logic changes for different reasons than infrastructure concerns.

The Dependency Inversion Principle in Action

Dependency inversion stands as the cornerstone principle enabling this architecture. Instead of your domain depending on concrete infrastructure implementations, both depend on abstractions defined by the domain itself. Your business logic defines interfaces (ports) that describe what it needs, and infrastructure provides implementations (adapters) that satisfy those contracts.

This inversion creates remarkable flexibility. Need to switch from REST to GraphQL? Change the inbound adapter. Want to move from MySQL to DynamoDB? Swap the outbound adapter. Crucially, your domain logic remains untouched, unaware that anything changed. The contracts it defined continue to be fulfilled, just by different implementations.

Identifying and Defining Ports in Your Application

Ports represent the application's boundary, defining how the outside world can interact with your domain logic and how your domain logic can interact with external systems. These aren't physical components but conceptual contracts—interfaces or abstract classes that declare capabilities without prescribing implementation details.

Two distinct types of ports serve different purposes in your architecture. Inbound ports (also called driving or primary ports) define operations that external actors can trigger on your application. These represent use cases or application services that orchestrate domain logic in response to external requests. Outbound ports (driven or secondary ports) define capabilities your domain logic needs from the outside world, such as persistence, messaging, or external service integration.

| Port Type | Direction | Purpose | Common Examples | Defined By |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inbound Port | Outside → Domain | Exposes application capabilities to external actors | CreateOrderUseCase, AuthenticateUserService, ProcessPaymentCommand | Application/Domain Layer |

| Outbound Port | Domain → Outside | Declares dependencies on external capabilities | OrderRepository, EmailNotifier, PaymentGateway | Domain Layer |

Designing Effective Inbound Ports

When designing inbound ports, focus on expressing business capabilities rather than technical operations. An inbound port named "CreateOrderUseCase" communicates intent far better than "OrderController" or "OrderEndpoint." The port should encapsulate a complete business operation, accepting all necessary input and returning meaningful results or raising domain-specific errors.

Each inbound port typically corresponds to a single use case or user story. This granularity ensures that ports remain focused and cohesive, avoiding the trap of creating god-like service interfaces that try to handle every possible operation. Small, focused ports are easier to test, understand, and maintain than sprawling interfaces with dozens of methods.

"Your ports should speak the language of your business, not the language of your technology stack. When a business analyst can read your port definitions and understand what your application does, you've succeeded."

Crafting Meaningful Outbound Ports

Outbound ports require a different mindset because they represent what your domain needs rather than what it provides. Design these interfaces from the perspective of your domain logic, expressing requirements in domain terms rather than technical jargon. An outbound port should be named "OrderRepository" not "DatabaseAccessLayer," and its methods should reflect domain operations like "findOrdersByCustomer" rather than technical operations like "executeQuery."

Keep outbound ports minimal and focused on specific capabilities. Rather than creating a single massive repository interface, consider multiple smaller ports that each handle distinct concerns. This approach, sometimes called Interface Segregation, ensures that adapters only need to implement the specific capabilities they provide, and domain logic only depends on exactly what it needs.

Building Adapters That Connect Your Domain to Reality

Adapters transform between the domain's pure business language and the messy reality of technical implementations. Each adapter implements one or more ports, bridging the gap between abstract contracts and concrete technologies. The beauty of adapters lies in their replaceability—swap one out for another, and your domain remains blissfully unaware.

Inbound adapters (also called primary or driving adapters) translate external requests into domain operations. These might be REST controllers that convert HTTP requests into use case invocations, CLI handlers that parse command-line arguments into domain commands, or message consumers that transform queue messages into application events. Each inbound adapter speaks two languages: the protocol of the external world and the domain's business language.

Implementing Inbound Adapters

An effective inbound adapter remains thin, focused solely on translation and delegation. It shouldn't contain business logic, validation rules, or decision-making code—those responsibilities belong in the domain. The adapter's job is to receive external input, convert it into domain-friendly formats, invoke the appropriate inbound port, and translate the result back into the external format.

- Parse and validate technical format — Handle HTTP parsing, JSON deserialization, or message queue format specifics

- Transform to domain types — Convert DTOs, request objects, or external formats into domain entities or value objects

- Invoke the inbound port — Call the appropriate use case or application service with properly formatted domain objects

- Handle domain results — Catch domain exceptions, process return values, and prepare responses

- Translate back to external format — Convert domain results into HTTP responses, command output, or message formats

Consider a REST adapter handling order creation. It receives an HTTP POST request with JSON payload, validates the JSON structure, extracts relevant fields, creates domain value objects for customer information and order items, invokes the CreateOrderUseCase port, catches any domain exceptions to return appropriate HTTP status codes, and finally serializes the resulting order entity back to JSON. At no point does this adapter make business decisions—it simply facilitates communication.

Constructing Outbound Adapters

Outbound adapters (secondary or driven adapters) implement the interfaces your domain defines, providing concrete implementations of required capabilities. These adapters contain all the technical complexity your domain avoids: database queries, HTTP client configuration, file system operations, or third-party API integration. Each outbound adapter isolates a specific technical concern, keeping infrastructure code contained and replaceable.

When building outbound adapters, resist the temptation to leak technical details back into the domain. If your repository port defines a method "findActiveOrders," the adapter might execute a SQL query with a WHERE clause filtering by status, but the domain never sees SQL. The adapter translates between domain concepts (active orders) and technical implementations (database queries), maintaining the abstraction boundary.

"The moment your domain entities start carrying ORM annotations or your business logic references database transaction managers, you've broken the architectural boundary. Keep infrastructure concerns firmly on the adapter side."

| Adapter Type | Implements | Responsibilities | Technology Examples | Typical Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REST Adapter | Inbound Port | HTTP request/response handling, routing, serialization | Express, Spring MVC, FastAPI | Status codes, headers, content negotiation |

| Database Adapter | Outbound Port | Query execution, transaction management, mapping | PostgreSQL, MongoDB, Redis | Connection pooling, query optimization, schema |

| Message Queue Adapter | Both | Message publishing/consuming, serialization | RabbitMQ, Kafka, SQS | Message format, retry logic, dead letters |

| External API Adapter | Outbound Port | HTTP client management, authentication, error handling | Payment gateways, shipping APIs | Rate limiting, timeouts, circuit breaking |

Structuring Your Domain Layer for Maximum Independence

The domain layer represents the heart of your application, containing all business logic, rules, and workflows that make your software valuable. This layer should be completely independent of any infrastructure concerns, frameworks, or external systems. Achieving this independence requires deliberate design choices about how you organize domain entities, value objects, services, and use cases.

Domain entities model the core business concepts that your application manages. These aren't anemic data structures but rich objects that encapsulate both state and behavior. An Order entity doesn't just hold order data—it enforces business rules about what constitutes a valid order, how orders transition between states, and what operations are permissible. By placing behavior alongside data, you ensure that business rules remain consistent and centralized rather than scattered across service layers.

Value Objects and Domain Primitives

Value objects provide a powerful tool for expressing domain concepts that don't have identity but do have meaning. Instead of representing an email address as a string, create an EmailAddress value object that validates format, handles comparison correctly, and makes your code's intent explicit. These objects eliminate primitive obsession, reduce validation duplication, and make your domain model self-documenting.

💡 Money, addresses, date ranges, product codes, and quantities all benefit from being modeled as value objects rather than primitives. This approach moves validation and behavior into the type system itself, making invalid states unrepresentable and eliminating entire classes of bugs.

Domain Services and Use Cases

Some business logic doesn't naturally belong to a single entity but instead orchestrates interactions between multiple domain objects. Domain services encapsulate these cross-entity operations, maintaining the domain layer's independence while handling complex workflows. A "TransferFunds" service might coordinate between multiple account entities, ensuring business rules about minimum balances, transfer limits, and transaction recording are all enforced.

Use cases (or application services) sit at the boundary between the outside world and your domain, implementing inbound ports by orchestrating domain logic to fulfill specific business operations. Each use case represents a single user goal or system capability, coordinating domain entities, domain services, and outbound ports to achieve the desired outcome. These use cases form the application's API, expressed in business terms rather than technical jargon.

"When your domain layer compiles without any infrastructure dependencies, you've achieved true independence. You can run domain tests in milliseconds, understand business logic without wading through framework code, and refactor infrastructure without fear."

Managing Dependencies Through Dependency Injection

Dependency injection serves as the mechanism that wires together your ports and adapters without coupling them. Rather than having domain code instantiate concrete adapter implementations directly, dependencies flow in through constructor parameters or method arguments, with the actual implementations provided by a composition root at application startup.

This approach enables the dependency inversion that makes the architecture work. Your domain defines what it needs through port interfaces, but never knows or cares about the concrete implementations. At runtime, a dependency injection container or manual wiring code provides the appropriate adapters, connecting everything together without creating compile-time dependencies from domain to infrastructure.

Composition Root and Application Bootstrap

The composition root represents the single place in your application where all the pieces come together. This is typically your main function or application bootstrap code, where you instantiate concrete adapters, wire them to ports, and start the application. By centralizing this wiring, you make it explicit how your application is configured and easy to swap implementations for different environments or testing scenarios.

- 🔧 Instantiate infrastructure adapters — Create concrete implementations of repositories, API clients, message publishers

- 🔧 Build domain services — Construct use cases and domain services, injecting outbound port implementations

- 🔧 Configure inbound adapters — Set up REST controllers, CLI handlers, or message consumers with references to inbound ports

- 🔧 Start the application — Initialize servers, connect to databases, begin listening for requests

Testing Strategies in Hexagonal Architecture

One of the most compelling benefits of this architectural approach manifests in testing. The clear separation between domain logic and infrastructure concerns enables fast, focused unit tests for business logic without requiring databases, web servers, or external services. This dramatically reduces test execution time and eliminates the brittleness that plagues integration-heavy test suites.

Domain layer tests run in isolation, using test doubles (mocks, stubs, or fakes) to satisfy outbound port dependencies. These tests execute in milliseconds, providing immediate feedback during development. Because domain code has no infrastructure dependencies, you can test complex business scenarios without the overhead of spinning up databases or external services.

Testing Inbound and Outbound Ports

Ports themselves define testable contracts. For inbound ports, write tests that verify use cases correctly orchestrate domain logic, enforce business rules, and handle both success and error scenarios. These tests treat the inbound port as a black box, invoking it with various inputs and asserting on outputs and side effects (via outbound port mocks).

Outbound ports benefit from contract tests that verify adapter implementations actually fulfill the port's contract. These tests run against the real infrastructure (database, message queue, external API) but focus narrowly on verifying that the adapter correctly implements the port's interface. Contract tests catch integration issues early while remaining focused and maintainable.

"The test pyramid naturally emerges from hexagonal architecture: many fast domain tests, some contract tests for adapters, and a few end-to-end tests for critical paths. You spend less time waiting for tests and more time confidently refactoring."

Integration and End-to-End Testing

While domain tests provide fast feedback, you still need integration tests that verify adapters work correctly with real infrastructure and end-to-end tests that validate complete user workflows. However, the architecture allows you to minimize these slower tests because you've already verified business logic in isolation and adapter contracts independently.

Integration tests focus on adapter behavior: does the database adapter correctly persist and retrieve entities? Does the REST adapter properly serialize responses? These tests use real infrastructure but remain narrowly scoped to specific adapters, making them faster and more maintainable than traditional integration tests that exercise the entire application stack.

Practical Implementation Patterns and Code Organization

Translating architectural concepts into actual code requires decisions about package structure, naming conventions, and module organization. While the specific details vary by language and framework, certain patterns consistently produce maintainable, understandable codebases that clearly express hexagonal principles.

Many teams organize code by architectural layer, creating separate modules or packages for domain, application, and infrastructure concerns. This structure makes the architecture explicit and prevents accidental dependencies from infrastructure into domain. Within each layer, further organization by feature or bounded context helps manage complexity as applications grow.

Package and Module Structure

A typical structure might include a domain package containing entities, value objects, and domain services; an application package with use cases and port definitions; and an infrastructure package with adapter implementations. Some teams prefer organizing by feature first, then by layer within each feature, which can work well for larger applications with distinct bounded contexts.

🎯 Domain entities and value objects should live in the deepest, most protected part of your package structure, with no dependencies on anything external. Application services and port interfaces form the next layer, depending only on domain. Infrastructure adapters sit at the outermost layer, depending on both application ports and external libraries.

Naming Conventions That Clarify Intent

Clear, consistent naming helps developers understand architectural boundaries at a glance. Prefix or suffix port interfaces to distinguish them from implementations: "OrderRepository" for the port, "PostgresOrderRepository" for the adapter. Use case classes often benefit from explicit naming like "CreateOrderUseCase" or "ProcessPaymentCommand" that clearly communicates their purpose.

Avoid technical names in domain code—"OrderService" tells you nothing about what it does, while "CalculateOrderTotal" or "ApplyDiscountRules" clearly expresses business intent. Reserve technical terminology for infrastructure code where it belongs: "RestOrderController," "JpaOrderRepository," "KafkaOrderEventPublisher."

"Code organization should make the architecture obvious. A developer joining the project should immediately understand what's domain logic, what's infrastructure, and where the boundaries lie—without reading documentation."

Handling Cross-Cutting Concerns

Certain concerns like logging, monitoring, security, and transaction management don't fit neatly into domain or adapter categories because they affect multiple layers. Handling these cross-cutting concerns without violating architectural boundaries requires careful thought and often involves aspect-oriented techniques or middleware patterns.

Logging serves as a prime example. Your domain shouldn't depend on a specific logging framework, but you still need visibility into what happens during business operations. One approach involves defining a domain-level logging port that expresses logging needs in business terms, with an adapter providing the concrete implementation. Alternatively, logging can be handled entirely at the adapter level, where inbound adapters log requests and responses while outbound adapters log external interactions.

Transaction Management

Transaction boundaries typically belong at the use case level, where you can clearly define what constitutes a single unit of work. Rather than scattering transaction management throughout domain code, implement it in the application layer or as an aspect that wraps use case execution. This keeps transaction concerns separate from business logic while ensuring data consistency.

Some teams implement a Unit of Work pattern as an outbound port, allowing domain code to participate in transactions without depending on specific transaction management frameworks. The adapter implementation handles the actual transaction lifecycle, committing or rolling back based on use case success or failure.

Security and Authorization

Security concerns often span multiple layers. Authentication typically happens at the adapter level—a REST adapter verifies JWT tokens before invoking use cases. Authorization, however, may involve business rules that belong in the domain. Consider defining authorization as a domain concept, with ports for retrieving user permissions and domain services for enforcing access rules.

🔐 Separate authentication (proving who you are) from authorization (what you can do). Authentication lives in inbound adapters, while authorization rules often belong in the domain because they express business policies about access and permissions.

Migrating Existing Applications to Hexagonal Architecture

Few teams have the luxury of starting fresh with a greenfield project. More commonly, you're working with an existing codebase that has accumulated technical debt, tight coupling, and architectural inconsistency. Migrating such applications to hexagonal architecture requires a pragmatic, incremental approach that delivers value continuously rather than attempting a risky big-bang rewrite.

Start by identifying a bounded context or feature area that's relatively isolated and would benefit most from architectural improvement. This becomes your beachhead for introducing hexagonal principles. Extract the business logic from this area into a domain layer, define ports for its dependencies, and implement adapters for existing infrastructure. This creates a pocket of clean architecture that can gradually expand.

The Strangler Fig Pattern

The strangler fig pattern, named after vines that gradually envelope and replace trees, provides an effective migration strategy. You build new functionality using hexagonal architecture alongside the existing system, gradually routing more requests to the new implementation while the old code remains operational. Over time, the new architecture "strangles" the old one until you can safely remove the legacy code.

- Identify migration candidates — Choose features or modules that are well-bounded and frequently changing

- Extract domain logic — Separate business rules from infrastructure code, moving them into a clean domain layer

- Define ports — Create interfaces for external dependencies, initially implemented by adapters that delegate to existing code

- Implement new adapters — Gradually replace legacy infrastructure with clean adapter implementations

- Route traffic incrementally — Use feature flags or routing logic to progressively move requests to new code

Dealing with Legacy Dependencies

Legacy systems often have deep, tangled dependencies that make clean separation difficult. Rather than attempting to untangle everything at once, create anti-corruption layers that isolate legacy code behind ports. These adapters translate between your clean domain model and the messy reality of existing systems, preventing legacy concerns from infecting new code.

As you build new features, implement them using hexagonal principles from the start. This prevents the problem from growing while you work on migrating existing code. Over time, the proportion of clean, well-architected code increases, and the legacy portions shrink until they can be replaced entirely.

"Migration isn't about achieving architectural purity overnight. It's about making each new feature better than the last, each refactoring more principled than before, until you look up one day and realize you have a maintainable system."

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even with the best intentions, teams implementing hexagonal architecture often stumble into predictable traps. Recognizing these pitfalls early helps you avoid costly mistakes and keeps your architecture clean and effective.

Anemic Domain Models

One of the most common mistakes involves creating domain entities that are nothing more than data containers, with all behavior extracted into service classes. This defeats the purpose of domain-driven design and hexagonal architecture, scattering business logic across service layers rather than encapsulating it within rich domain models. Combat this by actively looking for behavior that belongs with data and moving validation, business rules, and domain logic into entities and value objects.

Port Explosion

Some teams create excessive numbers of tiny, single-method ports, leading to a proliferation of interfaces that add complexity without adding value. While focused ports are good, taken to an extreme, this creates maintenance burden and obscures the architecture's intent. Aim for ports that represent cohesive capabilities—a repository port might have several related methods for finding, saving, and deleting entities rather than separate ports for each operation.

Leaky Abstractions

Ports sometimes leak implementation details from adapters back into the domain. A repository port that returns database-specific error types, accepts query objects from an ORM, or includes pagination parameters specific to a particular database violates the abstraction boundary. Keep ports expressed in pure domain terms, forcing adapters to handle the translation between domain concepts and technical implementations.

🚫 Watch for infrastructure types appearing in port signatures: database exceptions, HTTP status codes, framework-specific annotations, or ORM entities. These indicate abstractions that aren't abstract enough.

Advanced Patterns and Variations

Once you've mastered the fundamentals, several advanced patterns can enhance your hexagonal architecture implementation for specific scenarios or scale requirements.

Event-Driven Architecture Integration

Hexagonal architecture combines naturally with event-driven patterns. Domain events, raised by entities when significant business occurrences happen, can be published through outbound ports to event bus adapters. This enables loose coupling between bounded contexts while keeping the domain layer unaware of messaging infrastructure. Event handlers themselves can be implemented as inbound adapters that translate events into use case invocations.

CQRS and Read Models

Command Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) fits elegantly into hexagonal architecture. Commands flow through inbound ports to use cases that modify domain state, while queries bypass the domain entirely, going directly to optimized read model adapters. This separation allows you to optimize each side independently—rich domain models for commands, denormalized projections for queries—while maintaining clean architectural boundaries.

Multi-Adapter Scenarios

Real applications often need multiple adapters for the same port—a REST API and a CLI both implementing the same inbound ports, or repositories that can target either a relational database or a document store. The architecture handles this naturally through dependency injection configuration, allowing you to compose different adapter combinations for different deployment scenarios or runtime contexts.

"Advanced patterns shouldn't be adopted because they're sophisticated, but because they solve specific problems you're actually facing. Start simple, add complexity only when simpler solutions prove insufficient."

Measuring Success and Architectural Fitness

How do you know if your hexagonal architecture implementation is working? Several metrics and indicators help assess whether you're achieving the architecture's goals or drifting toward the same problems it's meant to solve.

Dependency direction provides the most fundamental metric. Tools that analyze package dependencies should show clear flow from infrastructure toward domain, never the reverse. If you find infrastructure packages depending on domain packages, that's expected. Domain packages depending on infrastructure indicates a boundary violation that needs correction.

Test Execution Speed

One practical benefit of hexagonal architecture manifests in test performance. Domain tests should execute in milliseconds because they have no infrastructure dependencies. If your unit tests require databases or web servers, you haven't achieved proper separation. Track the percentage of your test suite that runs without infrastructure—higher percentages indicate better architectural adherence.

Ease of Change

The ultimate test involves how easily you can make changes. Can you swap databases without touching domain code? Can you add a new API endpoint by creating a single adapter class? Can you test new business rules without starting the application? These capabilities indicate successful implementation. Difficulty making such changes suggests architectural boundaries need strengthening.

💪 Track how long it takes to onboard new developers. When team members can understand the domain layer without learning your framework choices, and can contribute to business logic without infrastructure expertise, your architecture is working.

Real-World Considerations and Trade-offs

No architecture is free—hexagonal architecture trades certain costs for its benefits. Understanding these trade-offs helps you make informed decisions about when and how to apply these patterns.

Increased Initial Complexity

Hexagonal architecture introduces more moving parts than simpler approaches. You're defining ports, implementing adapters, managing dependency injection, and maintaining architectural boundaries. For very small applications or prototypes, this overhead might outweigh the benefits. The architecture pays dividends as applications grow and evolve, but simple CRUD applications might not justify the investment.

Team Learning Curve

Developers unfamiliar with these patterns need time to internalize the concepts and understand where different concerns belong. This learning curve can slow initial development while the team builds architectural understanding. However, this investment typically pays off quickly as developers gain confidence in where to put new code and how to maintain boundaries.

Pragmatism Over Purity

Real projects sometimes require pragmatic compromises. Maybe you need to use framework-specific annotations in domain entities for the first release, planning to refactor later. Perhaps you can't fully isolate a particular external dependency due to technical constraints. These compromises don't invalidate the architecture—they're conscious trade-offs made with full awareness of the implications. The key is making such decisions deliberately rather than accidentally.

"Perfect architecture is the enemy of shipped software. Aim for good enough architecture that can evolve, not pristine architecture that never launches. The goal is sustainable development velocity, not architectural awards."

Hexagonal Architecture in Different Technology Stacks

While the principles remain constant, implementation details vary across programming languages and frameworks. Understanding how hexagonal architecture manifests in different ecosystems helps you apply these patterns effectively in your specific context.

Java and Spring Boot

Java's strong type system and interface support make hexagonal architecture natural to implement. Spring's dependency injection handles wiring, while package visibility controls enforce boundaries. Many teams organize code into separate Maven or Gradle modules for domain, application, and infrastructure, using module dependencies to prevent architectural violations.

JavaScript and TypeScript

JavaScript's flexibility requires more discipline to maintain boundaries, but TypeScript's interfaces and module system provide the necessary tools. Dependency injection can be handled through libraries like InversifyJS or simple factory functions. The lack of package-private visibility means teams rely more on code organization and review processes to maintain boundaries.

Python and FastAPI

Python's duck typing changes how ports and adapters work—rather than formal interfaces, you define protocols or abstract base classes. Dependency injection might use libraries like dependency-injector or rely on Python's flexible function arguments. The architecture works well with Python's philosophy of explicit over implicit, making dependencies and boundaries clear through deliberate code structure.

Go and Microservices

Go's interface system, where implementations satisfy interfaces implicitly, aligns naturally with hexagonal principles. The language's emphasis on simplicity and explicit dependencies matches the architecture's goals. Many Go microservices implement hexagonal architecture almost by default, with handlers as inbound adapters, business logic in domain packages, and repositories as outbound adapters.

What is the main benefit of hexagonal architecture?

The primary benefit is independence—your business logic becomes independent of frameworks, databases, and external systems. This independence enables faster testing (domain tests run without infrastructure), easier maintenance (changes to infrastructure don't affect business logic), and greater flexibility (swap implementations without rewriting core functionality). You can defer infrastructure decisions, test business rules in isolation, and evolve your application's technical foundation without touching domain code.

How do I know if I need hexagonal architecture?

Consider hexagonal architecture when your application has complex business logic that needs protection from infrastructure changes, when you need to support multiple interfaces (REST API, CLI, message queue), when testing is slow due to infrastructure dependencies, or when you anticipate significant evolution in technical choices. Small CRUD applications or prototypes might not justify the overhead, but applications with substantial business rules, long expected lifespans, or multiple integration points benefit significantly.

Can I use hexagonal architecture with existing frameworks?

Absolutely. Hexagonal architecture works with any framework—the framework simply becomes an adapter. Your REST controllers, ORM repositories, and message handlers are all adapters that connect your domain to specific technologies. The key is keeping framework-specific code in adapters while keeping domain logic free of framework dependencies. Most modern frameworks support dependency injection and interface-based programming, making integration straightforward.

How does hexagonal architecture differ from layered architecture?

Traditional layered architecture creates top-down dependencies where each layer depends on the layer below it, often resulting in business logic depending on data access layers. Hexagonal architecture inverts these dependencies—the domain layer defines interfaces (ports) that infrastructure implements (adapters), making business logic independent of technical concerns. This inversion enables testing without infrastructure and allows swapping implementations without touching domain code, advantages layered architecture doesn't provide.

What's the relationship between hexagonal architecture and domain-driven design?

Hexagonal architecture provides the structural pattern for organizing code, while domain-driven design (DDD) provides the tactical patterns for modeling the domain. They complement each other perfectly—DDD gives you rich domain models with entities, value objects, and aggregates, while hexagonal architecture protects those domain models from infrastructure concerns. You can use hexagonal architecture without DDD, but combining them creates applications with both clean structure and rich domain models that accurately reflect business complexity.

How do I handle transactions across multiple adapters?

Transaction management typically belongs at the use case level in the application layer. Define a Unit of Work pattern as an outbound port that your domain uses to coordinate transactional operations. The adapter implementation handles actual transaction management using your infrastructure's transaction mechanism (database transactions, distributed transactions, saga patterns). This keeps transaction concerns separate from business logic while ensuring data consistency across multiple operations.