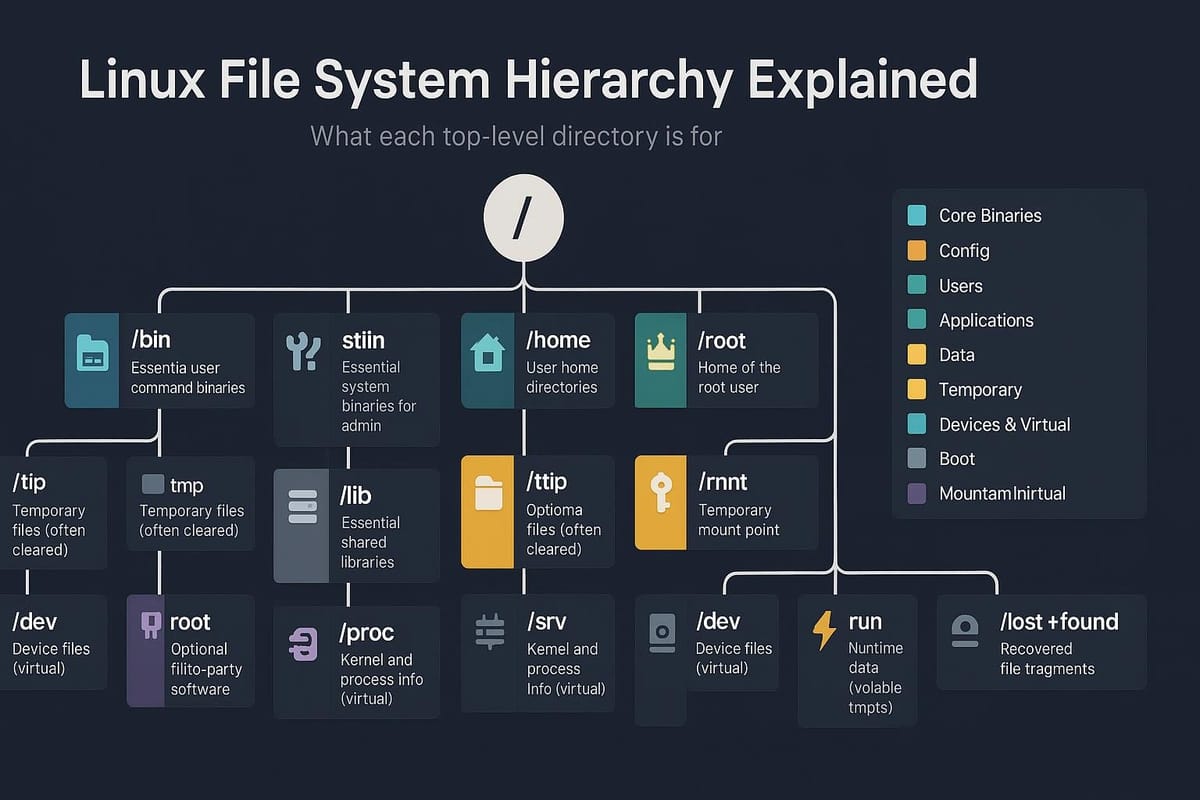

Linux File System Hierarchy Explained

Short introduction: The Linux file system hierarchy organizes files and directories so the system and users can find what they need predictably. This guide explains the common directories, how system and user space are separated, and practical commands to explore the filesystem safely.

Why the hierarchy exists and basic principles

Linux follows a standard layout (the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard, FHS) so distributions, packages, and administrators have a predictable structure. This makes backups, scripting, troubleshooting, and package management consistent across systems.

- Single root: Everything stems from / (root).

- Separation of roles: Binaries, libraries, configuration, runtime files, user data, and device/state information live in different places.

- Mount points: Different filesystems (like /home, /boot, removable media) are mounted into this tree.

Terminal example — list root-level directories:

# See top-level directories and types

ls -l /

# or a more compact view with sizes

du -shx /* 2>/dev/null | sort -h

Explanation: The ls -l / shows directory names and permissions. du -shx /* displays apparent sizes of each top-level directory, helping you identify heavy folders.

Core directories you’ll use frequently

Understanding the common directories helps when configuring services, installing software, or troubleshooting.

- /bin — essential user binaries (e.g., bash, ls) available in single-user mode.

- /sbin — system binaries for administration (e.g., ip, reboot).

- /usr — read-only shareable data: /usr/bin (most user programs), /usr/lib (libraries), /usr/local (locally compiled/installed software).

- /lib, /lib64 — shared libraries for binaries in /bin and /sbin.

- /etc — configuration files for system and services.

- /home — user home directories.

- /root — the root user’s home.

Example — inspect where a command lives:

# Find executables and libraries

which ls # path of ls

type -a python # shows which python is in PATH

ldd /bin/ls # libraries used by /bin/ls

Explanation: which and type -a show where commands are found in PATH; ldd lists library dependencies, useful for diagnosing missing libraries.

System vs user space and package placement

It’s important to know where packages install files vs where you put local or temporary files.

- /usr is for distribution-managed software (often read-only in containers or immutable systems).

- /usr/local is for admin-installed programs (doesn’t conflict with package manager).

- /opt is for optional add-on packages (often third-party big apps).

- /var holds variable data: logs (/var/log), spool (/var/spool), caches (/var/cache), and runtime data (/var/run or /run).

Terminal examples — check package files and local installs:

# List package-owned files (Debian/Ubuntu example)

dpkg -L bash | head -n 20

# Check what is in /usr/local and /opt

ls -la /usr/local

ls -la /opt

Explanation: Package managers maintain their own databases. Use dpkg -L or rpm -ql to discover where packages placed files. Keep local compiles under /usr/local or /opt to avoid clashing with package manager files.

Special and virtual filesystems: /proc, /sys, /dev, /tmp

Linux exposes system and kernel data through pseudo-filesystems that behave like directories but are not traditional disk files.

- /proc — process and kernel information (e.g., /proc/uptime, /proc//).

- /sys — sysfs: kernel objects and hardware information.

- /dev — device nodes representing hardware and virtual devices.

- /tmp — temporary files (cleared on reboot on many distros).

- /run — runtime data for processes (volatile, replaced older /var/run).

Examples — read kernel and process info:

# View uptime and CPU info

cat /proc/uptime

head -n 5 /proc/cpuinfo

# Inspect device nodes and mounted pseudo-filesystems

ls -l /dev | head

mount | grep -E 'proc|sys|devtmpfs|tmpfs'

Explanation: These filesystems are dynamic and reflect current kernel state. You can read many values directly, which is handy for scripts and debugging, but you generally should not create persistent files here.

Practical commands and a commands table

Here are common commands to inspect and manage filesystems safely, plus a table summarizing them.

Terminal examples — disk and mount checks:

# Show mounted filesystems and free space

mount | column -t

df -hT # shows FS type and human-readable sizes

# Check disk usage in a directory (exclude other filesystems)

du -shx /var/* | sort -h

Commands table:

| Command | What it does | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ls | List directory contents | ls -la /etc |

| du | Disk usage of files/directories | du -sh /home/* |

| df | Disk free space per filesystem | df -hT / |

| mount | Show mounted filesystems | mount |

| umount | Unmount a filesystem | sudo umount /mnt/usb |

| find | Find files by criteria | find /var -type f -mtime +30 |

| stat | File status (timestamps, size) | stat /etc/hosts |

| lsof | List open files | sudo lsof /var/log/syslog |

| chown | Change owner | sudo chown user:group /srv/data |

| chmod | Change permissions | sudo chmod 755 /usr/local/bin/script |

Explanation: These commands cover exploration, disk management, and basic permission changes. Use sudo when modifying system areas like /etc, /usr, /opt.

Commands for safe administration

When you need to modify system files or mount devices, follow these safe practices.

Example workflows:

# Safely mount a USB drive and inspect it

sudo mkdir -p /mnt/usb

sudo mount /dev/sdb1 /mnt/usb

ls -la /mnt/usb

# When done:

sync

sudo umount /mnt/usb

Explanation: Create mount points under /mnt or /media (depending on distro). Always sync or ensure no processes are using files before unmounting.

Common Pitfalls

- Editing files in /usr or /lib directly: package updates can overwrite or conflict with manual changes. Use /usr/local, /opt, or configuration overlays.

- Running destructive commands as root: avoid wildcards with rm as root (e.g., rm -rf / some-dir/*). Test with echo or ls first.

- Confusing /root and / (user home vs system root): root’s home is /root; the filesystem root / is the top of the tree — don’t store personal dotfiles in /.

Troubleshooting examples

Practical commands when things go wrong.

Example — find what's filling disk space:

# Check disk usage and largest directories

df -h

sudo du -shx /* 2>/dev/null | sort -h | tail -n 20

# Or focus on a directory

sudo du -sh /var/* | sort -h

Example — find files modified recently:

# Files modified in last 7 days in /etc

sudo find /etc -type f -mtime -7 -ls

Explanation: du -shx /* keeps du on same filesystem (avoids counting mounted filesystems like /home). find is useful to quickly locate sources of growth.

Next Steps

- Explore a live system: run the commands above on a non-critical machine or VM to get hands-on experience.

- Read the FHS: skim the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS) documentation for authoritative details.

- Practice safe edits: use version control (git) or backups for /etc and use /usr/local or /opt for custom software.

This guide gave a practical tour of the Linux filesystem hierarchy, common directories, virtual filesystems, and commands to inspect and manage files safely. Use the commands table and examples here as a quick reference while you learn.

👉 Explore more IT books and guides at dargslan.com.