Python Multithreading vs Multiprocessing Explained

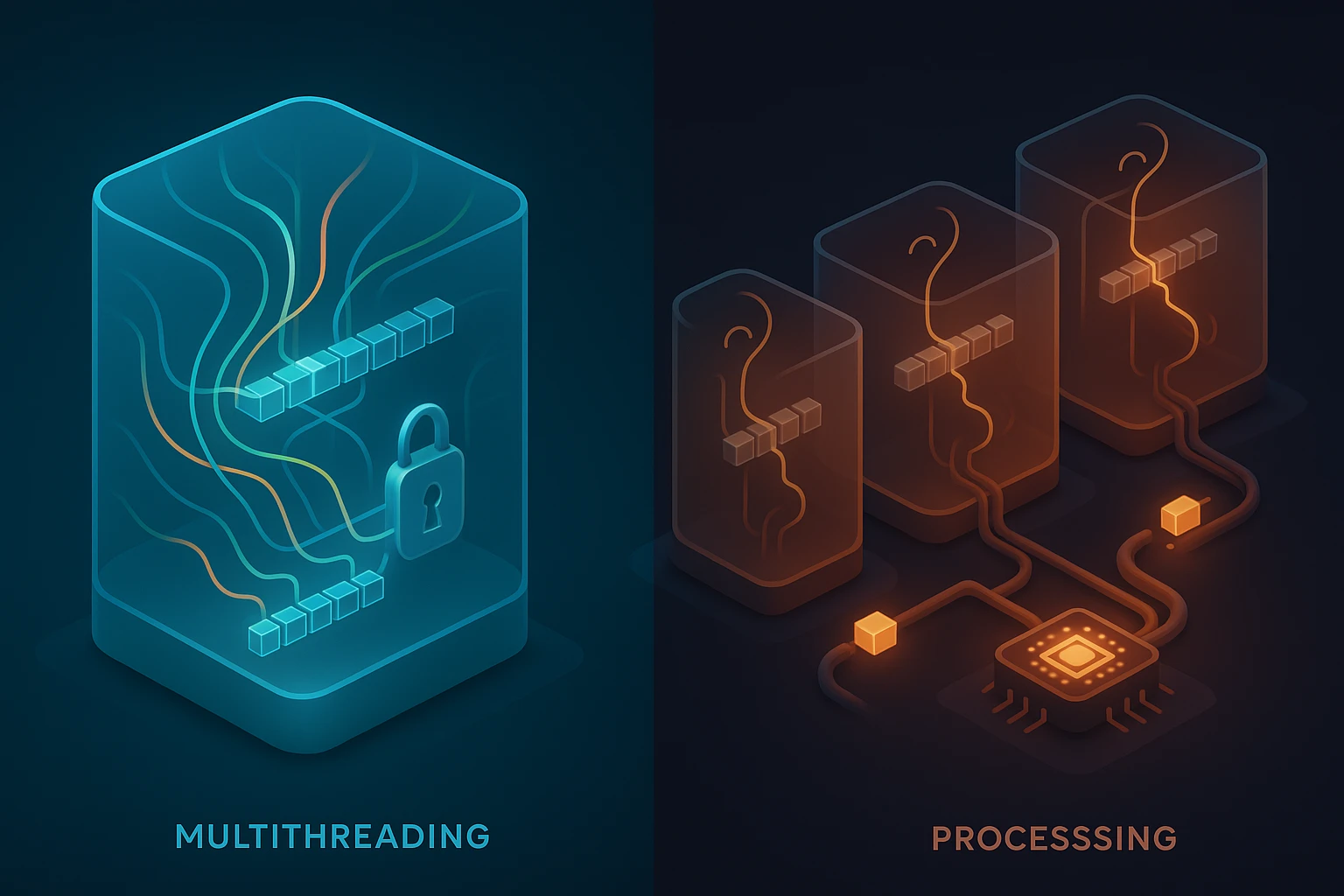

comparing Python multithreading and multiprocessing: threads share memory with GIL limits ideal for I/O; processes use separate memory, bypass GIL, suited for CPU-bound parallelism.

Sponsor message — This article is made possible by Dargslan.com, a publisher of practical, no-fluff IT & developer workbooks.

Why Dargslan.com?

If you prefer doing over endless theory, Dargslan’s titles are built for you. Every workbook focuses on skills you can apply the same day—server hardening, Linux one-liners, PowerShell for admins, Python automation, cloud basics, and more.

When building modern applications, performance isn't just a luxury—it's an expectation. Users demand responsiveness, data processing needs to happen in real-time, and computational tasks grow more complex by the day. Understanding how to leverage your system's resources effectively can mean the difference between an application that crawls and one that flies. The challenge lies in knowing which approach to concurrency will serve your specific needs, and more importantly, understanding the fundamental differences that make each technique shine in different scenarios.

Concurrency in Python revolves around two primary approaches: multithreading and multiprocessing. While both aim to execute multiple operations simultaneously, they operate on fundamentally different principles. Multithreading allows multiple threads to exist within a single process, sharing the same memory space, while multiprocessing spawns entirely separate processes, each with its own memory allocation. This distinction isn't merely technical—it shapes everything from performance characteristics to debugging complexity, and choosing incorrectly can lead to applications that perform worse than their single-threaded counterparts.

Throughout this exploration, you'll gain clarity on when to reach for threads versus processes, understand the notorious Global Interpreter Lock and its implications, discover practical implementation patterns, and learn to recognize the warning signs that indicate which approach your specific problem demands. Whether you're processing thousands of API requests, crunching numerical data, or building responsive user interfaces, the insights here will help you make informed architectural decisions that translate directly into better-performing applications.

Understanding the Fundamental Difference

The distinction between multithreading and multiprocessing begins at the operating system level. A thread represents the smallest unit of execution within a process—think of it as a lightweight worker that shares resources with other threads in the same process. These threads can access the same variables, objects, and memory locations, making data sharing straightforward but also introducing potential race conditions. In contrast, a process is an independent execution environment with its own memory space, system resources, and Python interpreter instance. Processes communicate through explicit mechanisms like pipes, queues, or shared memory objects, which adds overhead but provides isolation and true parallelism.

Python's threading implementation lives under the shadow of the Global Interpreter Lock, a mutex that protects access to Python objects and prevents multiple native threads from executing Python bytecode simultaneously. This architectural decision, made decades ago to simplify memory management and ensure thread safety for C extensions, means that CPU-bound Python code running in multiple threads won't execute in parallel on multiple cores. The GIL gets released during I/O operations, making multithreading excellent for network requests, file operations, and database queries—scenarios where your code spends most of its time waiting rather than computing.

"The Global Interpreter Lock isn't a design flaw—it's a deliberate trade-off that prioritized simplicity and compatibility over parallel execution for CPU-intensive tasks."

Multiprocessing sidesteps the GIL entirely by launching separate Python interpreter processes. Each process runs independently with its own GIL, enabling true parallel execution across multiple CPU cores. This approach excels when you're performing computationally intensive operations like image processing, mathematical calculations, or data transformations. The trade-off comes in the form of higher memory consumption—each process carries the full weight of a Python interpreter—and more complex inter-process communication requirements. Data that needs to move between processes must be serialized and deserialized, adding latency that doesn't exist in the shared-memory model of threading.

Memory Architecture Comparison

| Aspect | Multithreading | Multiprocessing |

|---|---|---|

| Memory Space | Shared across all threads | Separate for each process |

| Data Sharing | Direct access to variables | Requires serialization/IPC |

| Memory Overhead | Minimal (KB per thread) | Significant (full interpreter copy) |

| Startup Time | Fast (microseconds) | Slower (milliseconds) |

| GIL Impact | Limits CPU parallelism | No GIL restrictions |

When Multithreading Makes Sense

Multithreading shines brightest when your application spends significant time waiting for external resources. Web scraping represents a classic use case—your code sends HTTP requests and then sits idle while waiting for servers to respond. During these waiting periods, the GIL gets released, allowing other threads to execute. A single-threaded scraper might take hours to process thousands of URLs sequentially, while a multithreaded version can have dozens of requests in flight simultaneously, completing the same work in minutes.

Database operations follow similar patterns. When your application queries a database, the actual computation happens on the database server while your Python code waits for results. Threads can issue multiple queries concurrently, dramatically improving throughput for applications that need to aggregate data from multiple sources or execute independent queries. The shared memory model makes it trivial to collect results in a common data structure without the serialization overhead that multiprocessing would impose.

- 🌐 Network I/O operations including API calls, web scraping, and socket programming

- 💾 File system operations where reading and writing involves waiting for disk I/O

- 🗄️ Database queries that spend time waiting for external database servers

- 🖥️ User interface responsiveness by keeping UI threads separate from background work

- 📡 Real-time data streaming where multiple sources need concurrent monitoring

Responsive user interfaces represent another compelling use case. Desktop applications built with frameworks like Tkinter or PyQt need to remain responsive while performing background operations. Running long-running tasks in separate threads prevents the UI from freezing, allowing users to continue interacting with the application while data loads or processes in the background. The shared memory model means UI updates can happen directly without complex communication protocols.

"For I/O-bound tasks, multithreading can provide order-of-magnitude performance improvements with minimal code complexity—the GIL becomes irrelevant when your threads spend most of their time waiting."

Practical Threading Implementation

The threading module provides the foundation for concurrent execution. Creating threads involves instantiating Thread objects with target functions and starting them. The ThreadPoolExecutor from the concurrent.futures module offers a higher-level interface that manages thread lifecycle automatically, making it easier to parallelize operations across collections of data. Thread pools prevent the overhead of constantly creating and destroying threads, reusing workers for multiple tasks.

Synchronization primitives like locks, semaphores, and events become necessary when threads need to coordinate access to shared resources. A lock ensures that only one thread can modify a shared data structure at a time, preventing race conditions where simultaneous modifications lead to corrupted state. However, excessive locking can serialize execution, negating the benefits of threading. The art lies in identifying truly shared mutable state and protecting only what needs protection, allowing maximum concurrency for independent operations.

When Multiprocessing Becomes Essential

Computationally intensive tasks that keep the CPU busy represent the sweet spot for multiprocessing. Image processing operations—resizing, filtering, format conversion—involve heavy mathematical calculations that can fully utilize a CPU core. When processing thousands of images, distributing the work across multiple processes allows each core to work independently, achieving near-linear speedup with the number of available cores. The overhead of starting processes and transferring image data becomes negligible compared to the processing time saved.

Scientific computing and data analysis workloads frequently involve operations that can be parallelized across data partitions. Calculating statistics across large datasets, running simulations with different parameters, or applying transformations to data chunks all benefit from process-based parallelism. Libraries like NumPy release the GIL for many operations, but pure Python numerical code still suffers from GIL contention in multithreaded scenarios, making multiprocessing the clear choice for CPU-bound numerical work.

| Workload Type | Threading Performance | Multiprocessing Performance | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image Processing | Limited by GIL | Scales with cores | Multiprocessing |

| API Requests | Excellent scalability | Unnecessary overhead | Threading |

| Data Parsing (CPU) | No parallel benefit | Near-linear speedup | Multiprocessing |

| File Reading | Good for multiple files | Process overhead waste | Threading |

| Mathematical Computation | Serialized by GIL | Fully parallel | Multiprocessing |

Machine learning model training often involves embarrassingly parallel operations—training multiple models with different hyperparameters, performing cross-validation folds, or processing batches of training data. Multiprocessing allows these independent computations to run simultaneously, reducing training time from hours to minutes. The isolation between processes also provides a safety benefit—if one process crashes due to a bug or memory issue, other processes continue unaffected.

"When your application spends more time computing than waiting, multiprocessing transforms multiple CPU cores from idle resources into a performance multiplier."

Inter-Process Communication Patterns

The multiprocessing module provides several mechanisms for processes to exchange data. Queues offer thread-safe, process-safe data structures for passing messages between processes, following a producer-consumer pattern. Pipes create bidirectional communication channels between pairs of processes, useful for request-response patterns. Shared memory objects like Value and Array allow processes to access common data without serialization, though they require careful synchronization to prevent race conditions.

The Pool class provides a convenient abstraction for distributing work across a fixed number of worker processes. Methods like map() and apply_async() handle the complexity of dividing work, distributing it to workers, and collecting results. This pattern works beautifully for data-parallel problems where the same operation needs to apply to many independent data items—exactly the scenario where multiprocessing provides maximum benefit.

Performance Considerations and Trade-offs

The overhead of creating and managing concurrent execution varies dramatically between threading and multiprocessing. Thread creation takes microseconds and requires minimal memory—typically a few kilobytes for the thread stack. Process creation, however, involves forking the entire Python interpreter, copying memory pages, and initializing a new runtime environment. On Linux systems, this might take milliseconds per process; on Windows, where process creation is more expensive, it can take tens of milliseconds. For short-lived tasks, this startup cost can exceed the actual work being done.

Data transfer between processes incurs serialization overhead. Python uses the pickle module to serialize objects for inter-process communication, which means complex data structures get converted to byte streams, transmitted, and reconstructed in the receiving process. Large data structures can take significant time to pickle and unpickle. Threads avoid this entirely since they share memory, making data access instantaneous. This difference becomes critical when frequent communication is necessary—threading maintains its advantage even for CPU-bound tasks if constant data exchange is required.

"The best concurrency approach isn't determined by abstract principles—it's dictated by profiling your specific workload and understanding where time actually gets spent."

Memory consumption scales differently for each approach. Threading adds minimal overhead regardless of thread count—ten threads might add only a few megabytes to your application's footprint. Multiprocessing multiplies memory usage by the number of processes since each carries a complete Python interpreter and copies of imported modules. An application using 100MB of memory in single-process mode might consume 400MB with four processes. For memory-constrained environments or applications that need many concurrent workers, this difference becomes a deciding factor.

Debugging and Development Experience

Multithreaded code presents unique debugging challenges. Race conditions—bugs that appear only when specific timing conditions align—can be maddeningly difficult to reproduce and diagnose. Deadlocks occur when threads wait for each other to release resources, causing the entire application to freeze. Traditional debugging tools struggle with multithreaded code because stepping through one thread affects the timing of others, potentially hiding or altering the bug you're trying to find. Thread-safe programming requires discipline and careful reasoning about shared state.

Multiprocessing offers cleaner debugging in some respects since processes are isolated. A crash in one process doesn't corrupt the memory of others, making it easier to identify which component failed. However, debugging inter-process communication can be challenging—messages might get lost, deadlocks can occur in queues or pipes, and tracing execution across process boundaries requires different tools. The trade-off is between the complexity of shared-state concurrency versus the complexity of distributed-state concurrency.

Hybrid Approaches and Modern Alternatives

Real-world applications often benefit from combining both approaches. A web server might use multiprocessing to handle multiple requests in parallel, with each process using threading for I/O-bound operations within a single request. This hybrid model leverages the strengths of both paradigms—processes provide CPU parallelism while threads enable efficient I/O concurrency within each process. Popular frameworks like Gunicorn for web applications employ this pattern, spawning multiple worker processes that each handle many concurrent connections using threads or async I/O.

Asynchronous programming with asyncio represents a third approach that deserves consideration. Instead of using threads or processes, async code uses a single-threaded event loop that switches between tasks when they're waiting for I/O. This model provides excellent performance for I/O-bound workloads with lower overhead than threading—no context switching between threads, no GIL contention, and minimal memory footprint. However, async code requires different programming patterns and doesn't help with CPU-bound operations.

"The future of Python concurrency isn't about choosing one approach—it's about understanding when each tool fits and combining them intelligently."

- ⚡ Asyncio excels for high-concurrency I/O with lower overhead than threading

- 🔄 Hybrid models combine processes for CPU parallelism with threads for I/O

- 🚀 Third-party libraries like Ray or Dask provide distributed computing abstractions

- 🔧 Native extensions written in C or Rust can release the GIL for true threading

- 🌟 Python 3.13+ experiments with optional GIL removal for future possibilities

Making the Right Choice for Your Application

Start by profiling your application to understand where time gets spent. Tools like cProfile reveal whether your code is CPU-bound or I/O-bound. If most time goes to network calls, database queries, or file operations, threading or asyncio will provide the best results. If profiling shows heavy CPU usage in pure Python code—tight loops, mathematical calculations, data transformations—multiprocessing becomes the clear choice. Don't optimize based on assumptions; measure first.

Consider the nature of your data sharing requirements. Applications that need frequent communication between concurrent workers favor threading's shared memory model. If workers operate independently on separate data chunks, reporting only final results, multiprocessing's isolation becomes an advantage rather than a hindrance. The communication pattern between concurrent units of work often matters more than the raw computational characteristics.

"Premature optimization leads to complex code that doesn't address actual bottlenecks—profile first, then choose the concurrency model that targets your specific performance constraints."

Think about scalability requirements. Threading scales well to dozens of concurrent operations but hits diminishing returns beyond that due to GIL contention and context switching overhead. Multiprocessing scales naturally to the number of CPU cores but becomes impractical beyond that without distributed computing frameworks. For massive scale, consider whether your problem might benefit from distributed solutions like Celery for task queues or Dask for parallel computing across multiple machines.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

The most frequent mistake involves using multithreading for CPU-bound tasks, expecting parallel speedup that never materializes. Developers coming from languages without a GIL often assume threading will parallelize any workload, leading to disappointment when CPU-intensive threaded code runs no faster—or even slower due to context switching overhead—than single-threaded code. Always verify that threading provides actual benefits through benchmarking before committing to a threaded architecture for computational tasks.

Multiprocessing pitfalls often revolve around data transfer overhead. Passing large objects between processes can create bottlenecks that eliminate the performance gains from parallelization. Design your multiprocessing architecture so that workers receive small input parameters and return small results, keeping the bulk of data processing within each process. When large datasets must be shared, consider using shared memory objects or memory-mapped files rather than passing data through queues or pipes.

Synchronization errors plague both approaches but manifest differently. In threading, forgetting to protect shared state with locks leads to race conditions and data corruption. In multiprocessing, improper queue or pipe handling can cause deadlocks when buffers fill up. The solution involves understanding the synchronization primitives available—locks, semaphores, events, conditions for threading; queues, pipes, and managers for multiprocessing—and applying them correctly. When in doubt, prefer higher-level abstractions like ThreadPoolExecutor or multiprocessing.Pool that handle synchronization internally.

What's the main difference between threads and processes in Python?

Threads run within a single process and share memory space, making data sharing easy but limiting CPU parallelism due to the Global Interpreter Lock. Processes run independently with separate memory spaces, enabling true parallel execution across CPU cores but requiring explicit inter-process communication mechanisms. Threads are lightweight and fast to create, while processes carry more overhead but provide isolation and full CPU utilization.

When should I use multithreading instead of multiprocessing?

Choose multithreading for I/O-bound operations where your code spends time waiting for network requests, file operations, or database queries. Threading provides excellent concurrency for these workloads because the GIL gets released during I/O operations, allowing other threads to execute. Threading also makes sense when you need frequent data sharing between concurrent operations since threads share memory directly without serialization overhead.

Does multiprocessing always provide better performance for CPU-intensive tasks?

Multiprocessing provides better performance for CPU-intensive tasks only when the computational work outweighs the overhead of process creation and inter-process communication. For very short tasks, the time to spawn processes and transfer data can exceed the actual computation time. Additionally, multiprocessing benefits diminish beyond the number of physical CPU cores. Always profile to verify that multiprocessing improves your specific workload rather than assuming it will help.

How do I share data between processes safely?

Use the mechanisms provided by the multiprocessing module: Queues for message passing, Pipes for bidirectional communication between process pairs, and shared memory objects like Value and Array for common data. For complex objects, consider using a Manager which provides proxy objects that handle synchronization automatically. Avoid sharing data through global variables or files without proper locking, as this leads to race conditions and data corruption.

Can I use both threading and multiprocessing in the same application?

Absolutely, and this hybrid approach often provides the best performance. You might use multiprocessing to distribute CPU-intensive work across cores, with each process using threading for I/O operations. Web servers commonly employ this pattern—multiple worker processes handle requests in parallel, with each process using threads or async I/O for concurrent request handling. The key is understanding which concurrency model fits each part of your application's workload.

What's the impact of the Global Interpreter Lock on my code?

The GIL prevents multiple threads from executing Python bytecode simultaneously, meaning CPU-bound Python code in multiple threads won't run in parallel. However, the GIL gets released during I/O operations and when calling C extensions that explicitly release it, making threading effective for I/O-bound workloads. For CPU-bound pure Python code, you'll see no speedup from threading and should use multiprocessing instead to achieve true parallelism.