Understanding Environment Variables in Linux

Learn what Linux environment variables are, how they work, and why they matter for shells, scripts, and services. Practical examples and simple tips to view, set, export, and persist variables for DevOps beginners.

Short introduction

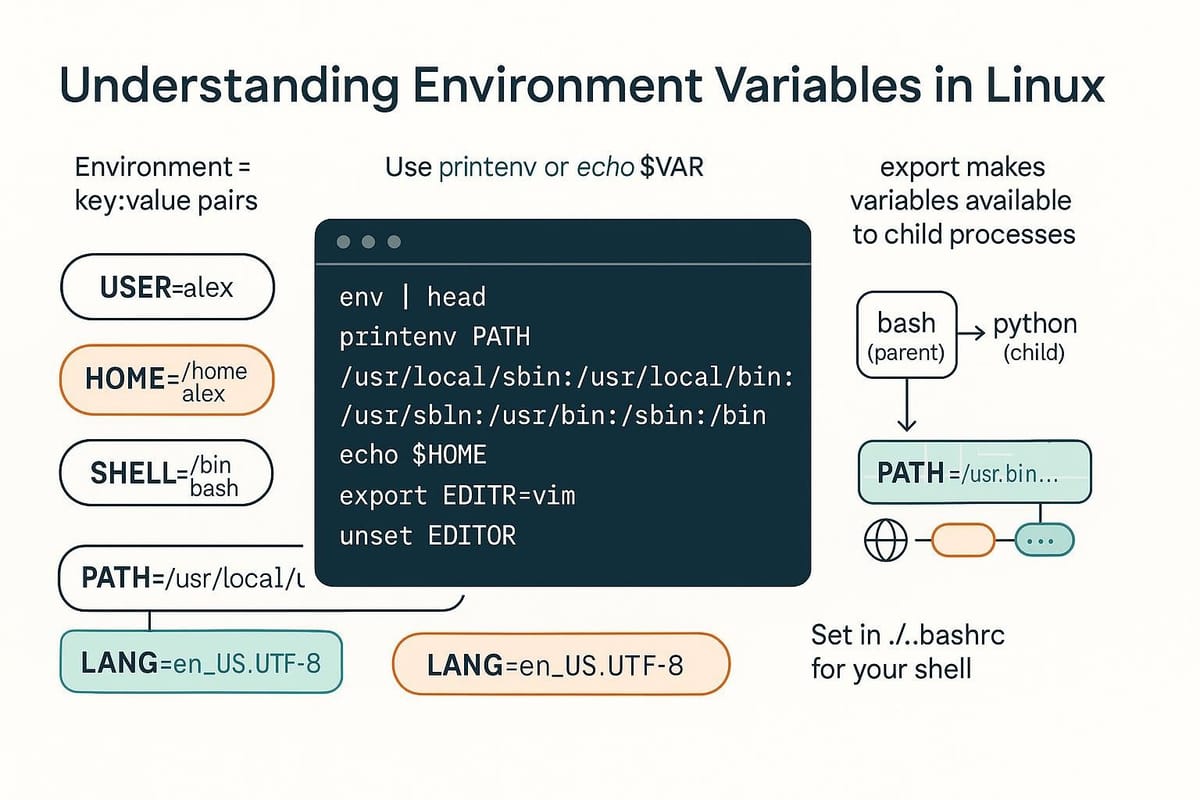

Environment variables are key-value pairs used by the shell and programs to control behavior, paths, credentials, and configuration. This guide explains what they are, how to view and set them, how to persist them, and how to use them safely in scripts and services.

What are environment variables?

Environment variables are strings exported into a process's environment so that the process and its child processes can read them. They affect programs in many ways: PATH determines where executables are searched for, HOME points to the user’s home directory, LANG affects locale settings, and custom variables can enable feature toggles or provide configuration values.

Example: read a variable in the shell

$ echo $HOME

/home/alice

$ echo $PATH

/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin

You can create short-lived variables for a single command:

$ TZ=UTC date

Mon Jan 1 12:00:00 UTC 2024

That TZ is visible to date (and its child processes) only for this invocation.

Viewing, listing, and common commands

You often need to list all environment variables or check a particular one. There are multiple commands and shells have built-ins that behave slightly differently.

Common ways to view environment variables:

- printenv: prints environment variables (simple and common)

- env: runs a command in a modified environment or lists env vars without arguments

- set: in bash, lists shell variables and functions (more verbose)

- export -p: lists exported variables (bash/zsh)

- echo $VAR: shows one variable

Terminal examples:

$ printenv | head -n 20

PATH=/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin

HOME=/home/alice

LANG=en_US.UTF-8

...

List only variables matching a pattern:

$ env | grep -i proxy

http_proxy=http://proxy.example:3128

HTTP_PROXY=http://proxy.example:3128

Exported vs shell-local variables:

$ MYVAR=hello

$ python -c 'import os; print(os.environ.get("MYVAR"))'

None

$ export MYVAR=hello

$ python -c 'import os; print(os.environ.get("MYVAR"))'

hello

Setting and exporting variables (temporary and persistent)

Temporary (current shell / single command) vs persistent (across sessions). A plain assignment sets a shell variable; export turns it into an environment variable visible to child processes.

Set for current shell only:

$ FOO=bar

$ echo $FOO

bar

Set and export for children:

$ export FOO=bar

$ bash -c 'echo $FOO'

bar

Set for a single command:

$ FOO=bar python -c 'import os; print(os.environ.get("FOO"))'

bar

# FOO is not present afterwards

$ echo $FOO

Make variables persistent (common places):

- ~/.bashrc or ~/.bash_profile or ~/.profile for interactive login/non-login shells

- /etc/environment for system-wide simple key=value pairs (not shell expansions)

- systemd service files (Environment= or EnvironmentFile=)

- For non-shell apps, configuration files or secret managers are better

Example: add to ~/.bashrc

# ~/.bashrc

export EDITOR=vim

export PATH="$HOME/bin:$PATH"

After editing, apply:

$ source ~/.bashrc

Example: system-wide (/etc/environment)

# /etc/environment

LANG="en_US.UTF-8"

JAVA_HOME="/usr/lib/jvm/java-17-openjdk"

Note: /etc/environment does not support shell expansions like $HOME.

Using environment variables in scripts and tools

Scripts rely heavily on environment variables to be portable and configurable. Use parameter expansion to provide defaults and fail-fast behavior.

Read a variable with a default:

#!/bin/bash

# myscript.sh

PORT=${PORT:-8080} # default to 8080 if PORT is unset or empty

echo "Starting service on port $PORT"

Fail if a required variable is missing:

#!/bin/bash

: "${DATABASE_URL:?DATABASE_URL must be set}"

# script exits with a message if DATABASE_URL is not defined

Using environment variables with systemd:

# /etc/systemd/system/myapp.service

[Service]

Environment="APP_ENV=production" "PORT=8000"

EnvironmentFile=/etc/myapp/envfile

ExecStart=/usr/bin/myapp

Substitute variables in config templates (example using envsubst):

$ cat config.template

listen ${PORT}

$ export PORT=8080

$ envsubst < config.template > config.conf

$ cat config.conf

listen 8080

Security tip: avoid putting secrets into world-readable dotfiles. Use restricted files (600) or secret managers.

Commands table

Below is a quick reference table for commonly used commands related to environment variables.

| Command | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|

| env | List environment variables or run a command in modified env | env | grep HOME |

| printenv | Print environment variables (single or all) | printenv PATH |

| export | Make a shell variable part of the environment | export EDITOR=vim |

| unset | Remove a variable from the environment/shell | unset FOO |

| set | In bash, list shell variables and functions | set | head |

| source (.) | Reload a file in the current shell | source ~/.bashrc |

| envsubst | Substitute env vars in input | envsubst < template > out |

| grep | Filter listings for patterns | env | grep -i proxy |

Example terminal usage:

$ export MYAPP_DEBUG=1

$ env | grep MYAPP

MYAPP_DEBUG=1

$ unset MYAPP_DEBUG

$ echo $MYAPP_DEBUG

Common Pitfalls

- Mixing shell-local and exported variables: setting VAR=value does not make it available to child processes unless you export it. This frequently causes programs to see a missing value.

- Putting secrets in plain, world-readable files: storing API keys in ~/.bashrc or /etc/environment without proper permissions can leak credentials. Use secure storage or restrict file permissions (chmod 600).

- Expecting shell expansions in files that don't support them: /etc/environment is read by PAM and does not perform $HOME or command substitutions. If you rely on expansions, use shell rc files (~/.bashrc) or manage with systemd EnvironmentFile.

Example showing first pitfall:

$ SECRET=topsecret

$ bash -c 'echo $SECRET'

# nothing printed because SECRET wasn't exported

$ export SECRET=topsecret

$ bash -c 'echo $SECRET'

topsecret

Next Steps

- Try practical experiments: use printenv, env, export, and unset in an interactive shell and observe child process visibility.

- Persist a simple variable (e.g., EDITOR) in ~/.bashrc, source it, and verify it appears for new shells and child processes.

- Learn about secure secret management (e.g., systemd secrets, HashiCorp Vault, or cloud provider secret stores) before placing sensitive data in environment variables.

This overview should give you the basics to view, set, and use environment variables in Linux safely and effectively.

👉 Explore more IT books and guides at dargslan.com.