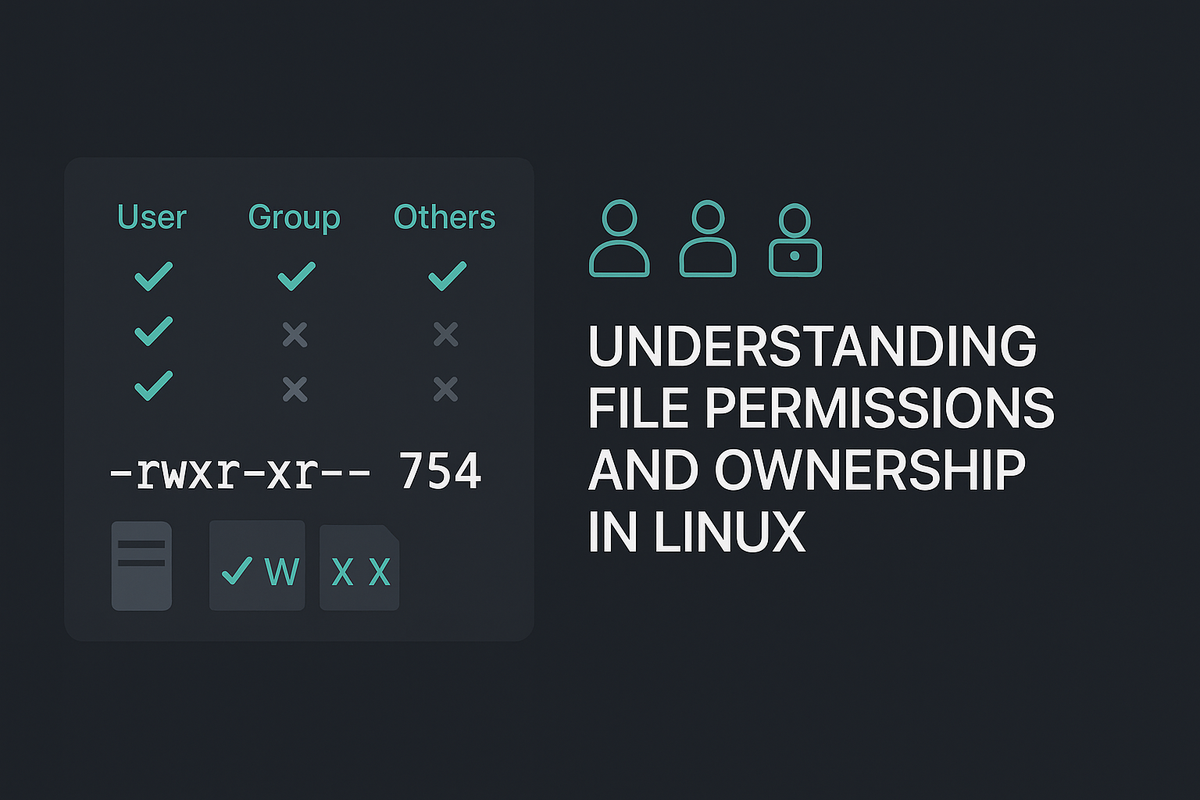

Understanding File Permissions and Ownership in Linux

Learn Linux file permissions and ownership basics, including rwx bits, users, groups, and chmod/chown usage. Practical examples and commands for Linux and DevOps beginners to secure and manage files.

Introduction

File permissions and ownership are the foundation of Linux system security and collaboration. Understanding how to read and change permissions helps you control who can read, write, or execute files and directories. This guide walks you through the essentials with practical examples you can run safely on a test folder.

File ownership and permission basics

Every file and directory on a Linux filesystem has an owner and a group and three sets of permissions: owner (user), group, and others. The most common way to see these is with ls -l.

Example: list details for files

$ ls -l

-rw-r--r-- 1 alice staff 1234 Apr 1 12:00 notes.txt

drwxr-x--- 2 bob devs 4096 Apr 2 09:00 project/

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 5432 Apr 3 18:30 script.sh

How to read that:

- The first column (-rw-r--r--) shows the file type and permissions:

- First character: "-" = file, "d" = directory, "l" = symlink.

- Next three characters: owner permissions (read r, write w, execute x).

- Next three: group permissions.

- Last three: others' permissions.

- The numbers show hard link count; then owner (alice), group (staff), size, date, and filename.

Notes:

- For directories, the execute bit (x) controls the ability to enter (cd) and traverse the directory.

Use stat for a concise numeric view:

$ stat -c "%n: %A %a" notes.txt

notes.txt: -rw-r--r-- 644

This prints the symbolic mode and the numeric mode (644).

Symbolic vs numeric permission modes (chmod)

You can change permissions using symbolic (u/g/o/r/w/x) or numeric (octal) modes with chmod.

Symbolic examples:

# Give execute to owner and group

$ chmod ug+x script.sh

# Remove write for others

$ chmod o-w notes.txt

# Set file to be readable by everyone but writable only by owner

$ chmod u=rw,go=r notes.txt

Numeric (octal) examples:

- Each permission triplet converts to an octal digit: read=4, write=2, execute=1.

- Owner, group, others form three digits.

# 644 = rw- r-- r--

$ chmod 644 notes.txt

# 755 = rwx r-x r-x (common for executable programs)

$ chmod 755 script.sh

# 700 = rwx --- ---

$ chmod 700 private_dir

Practical tip: Use numeric modes for predictable results and symbolic modes when adding/removing specific bits.

Changing ownership and group (chown, chgrp)

Ownership controls who is considered the file's "owner" and which group owns it. Only root (or a user with CAP_CHOWN) can change the owner. Regular users can change a file's group to a group they belong to (if supported) using chgrp.

Basic chown and chgrp usage:

# Change owner to alice and group to staff

$ sudo chown alice:staff notes.txt

# Change only the owner

$ sudo chown bob notes.txt

# Change only the group

$ chgrp devs project

# Recursively change ownership of a directory

$ sudo chown -R alice:devs project/

When to use:

- chown is commonly used when moving files between users or when files are created by root (e.g., installing software).

- chgrp is useful to share files with a team: set the group to the project group and give group write permission.

Example: share a folder with a group

# Create folder and set group

$ mkdir team-folder

$ sudo chown root:devs team-folder

$ chmod 2775 team-folder # setgid + rwxrwsr-x (see special perms section)

This allows files created inside to inherit the directory's group (setgid bit).

Special permissions: setuid, setgid, sticky bit

Besides rwx bits, Linux has three “special” bits that modify behavior: setuid, setgid, and the sticky bit.

- setuid (4xxx): when set on an executable, the process runs with the file owner's permissions.

- setgid (2xxx): when set on an executable, the process runs with the file's group; when set on a directory, new files inherit the directory group.

- sticky bit (1xxx): when set on a directory, files inside can be removed/renamed only by file owner, directory owner, or root. Common in /tmp.

Examples and detection:

# Set setuid on an executable

$ sudo chmod 4755 /usr/local/bin/special_run

# ls will show an 's' in place of the owner's execute bit:

$ ls -l /usr/local/bin/special_run

-rwsr-xr-x 1 root root 12345 Jun 1 12:00 /usr/local/bin/special_run

# Setgid on a directory (group inheritance)

$ chmod 2775 shared_dir

$ ls -ld shared_dir

drwxrwsr-x 2 alice devs 4096 Jun 1 12:10 shared_dir

# Sticky bit on /tmp (commonly)

$ ls -ld /tmp

drwxrwxrwt 14 root root 4096 Jun 1 12:00 /tmp

Be cautious:

- setuid programs can be security-sensitive; avoid setting setuid on scripts and only use it when necessary.

- setgid on directories is very useful for team collaboration.

umask and ACLs (fine-grained control)

umask sets the default permission “mask” applied when new files and directories are created. It subtracts bits from the system defaults.

Common umask examples:

# Show current umask

$ umask

0022

# Set umask so new files are group-writable (e.g., for collaborative environments)

$ umask 0002

Interpretation: default new file mode is typically 666 for files and 777 for directories; umask removes bits. With umask 0022, new files become 644 and directories 755.

Access Control Lists (ACLs) allow per-user/group permissions beyond the basic three sets. Use setfacl/getfacl to manage them.

# Give user carol read and write on a file

$ setfacl -m u:carol:rw notes.txt

# View ACLs

$ getfacl notes.txt

# Remove ACL entry

$ setfacl -x u:carol notes.txt

ACLs are useful when multiple specific users need tailored access without restructuring groups.

Common Pitfalls

- Using chmod 777 as a shortcut: it opens files to everyone and is rarely needed; prefer precise permissions or group-based access.

- Forgetting that execute bit on directories is required: users need the x bit to cd or list contents even if they have read permission.

- Running recursive chown/chmod (-R) carelessly: it can change ownership/permissions of system files or entire home directories unintentionally — test on a small subtree first.

Next Steps

- Practice in a safe test directory: create files and experiment with chmod, chown, umask, setgid, and sticky bit to see effects.

- Read man pages: man chmod, man chown, man setfacl for authoritative details and options.

- Learn about user/group management and sudo: understanding users, groups, and privilege delegation complements file permission management.

👉 Explore more IT books and guides at dargslan.com.